This book has 155 pages of the largest text I’ve ever seen in a book not for children or blind people, and one argument: everyone is conspiring against you. Your government, your church, your neighbors, your friends, your favorite sitcom star, and your cat. The conspiracy goes to the top, to the bottom, to the sides, and perhaps it even exists inward, inside your flesh. Trust no body. Not even your own.

But when you point at everything, you’re really pointing at nothing, and Jones’ omni-conspiracy makes no sense. This book doesn’t provide a coherent picture of anything except one man’s untreated mental health problems.

I wonder how Jones got Descent Into Tyranny published in the face of a globe-spanning totalitarian dictatorship. It couldn’t have been easy. The One World Government (which really exists and includes the Bush family, Gorbachev, Kissinger, Mao, “Adolph” Hitler, Stalin, Reagan, Osama bin Laden, and every billionaire and member of royalty worldwide) should have caused him to vanish into a black van years ago. Alex Jones’ worldview has no space in it for Alex Jones: he doesn’t realize this or doesn’t care. He’s like a man claiming that evil fairies will kill you if you speak of their existence: an obvious liar just by drawing breath. Jones is impossible to take seriously and his closing request that you wire him money – “The Republic is in great danger of being completely overthrown” – provokes the response “you just told me that every President since Eisenhower meets annually at Bohemian Grove to perform human sacrifice. What’s left to overthrow?”

But logical consistency isn’t important to Jones or his audience. A 2012 study found that conspiracy theories form a positive correlation matrix. Belief in one predicts belief in a second (and a third, etc). This remains true even when the theories contradict each other. In other words, if you answer “yes” to the statement “Princess Diana faked her own death”, you are more likely to answer “yes” to the statement “Princess Diana was murdered.”

I’ve seen Holocaust deniers argue (in message board posts 2 days apart) that Auschwitz had no crematoriums, and also that Auschwitz’s crematoriums would have only been able to burn a few thousand bodies in the time available. I’ve seen 9/11 truthers argue that no plane hit the WTC, and also that the Flight 93 hijackers were CIA patsies.

Sane people want to make sense of the world: they might be wrong about everything, but at least they will be wrong in an internally sensible wrongness. Conspiracy theorists, however, are driven by narcissism of the intellect: they alone know the truth, and everyone else is a sheep. They binge-watch Youtube videos and doomscroll Twitter because this validates them as people: they’re Neo, taking the red pill, committing an unthinkable act of bravery just by sitting in front of their laptop, ingesting nonsense. Theories are like dollars: the more of them you have, the richer you are. The fact that their fortune is in fools gold, counterfeit notes, and rubber checks doesn’t matter to them.

I found Descent into Tyranny to be a slog. Jones has the loud, bullying style of a radio host who’s used to steamrolling over guests and callers, and reading his book makes me feel like I’m being yelled at. I pity whoever has Jones over for Thanksgiving dinner; you couldn’t hold a reasonable conversation with this person about anything.

Sometimes Jones’ gonzo style produces funny results. On page 15 he repeats the story of Nero fiddling while Rome burned, but he gets it mixed up: he has Nero fiddling while setting fire to Rome (was he holding a firebrand between his toes?). Mostly, though, it plunges the book even deeper into its own epistemic quicksand. On page 101, he writes “For years, we warned people about FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency). The federal documents have been around for decades and include round-up plans and concentration camps.” End of section. Begin new section. This handwaving would be acceptable on a radio show, but this is a book. Can we see excerpts from these “federal documents”, or would that bloat Descent into Tyranny‘s length to an unpublishable 156 pages?

Descent Into Tyranny was written in 2002. I was curious to see how Jones’ political outlook evolved over time, as I remember Infowars being a left-libertarian website at the start. The book certainly has time for conspiracies beloved of the left: IMF, the World Bank, David Koresh as a harmless hippie victimized by The Man(tm), etc. It was published by a small outlet called Progressive Press, whose other excellent titles can be viewed online. (Excerpt: “The “Arab Spring” is revealed as part of the scheme to extend the Anglo-Zionist empire and its neo-liberal regime of plunder over the entire planet.”).

Jones was less fond of “Vladymir Putin” (sic) in 2002. In the section entitled “Putin Uses Terror”, he reveals that Putin destroyed an apartment complex using explosive plastique, killing 350 people. Fifteen years later Jones would be on Twitter writing stuff like “Looking forward to Putin giving me the new hashtags to use against Hillary and the dems… “ In fairness, Putin killed 350 people a long time ago. You have to let stuff slide eventually.

Jones runs out of material by the end, so he pads out the book with the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the Communist Manifesto (which was written by “global banking cartels”.) It’s gratuitous and farcical. He should have thrown in Huckleberry Finn and Of Mice and Men, then the book could have been a middle schooler’s summer reading list. Infowars’ slogan is “there’s a war on for your mind!” Alex Jones’ personal solution is to not have one.

A doorstop-sized work of historical fiction from 14th century China. At eight hundred pages, nearly a million words, and a thousand named characters, it has broken hardier men than you. Romance of the Three Kingdoms is one of those Mount Everest type books – can you possibly finish it?

It’s also the world’s first videogame. Explanation incoming.

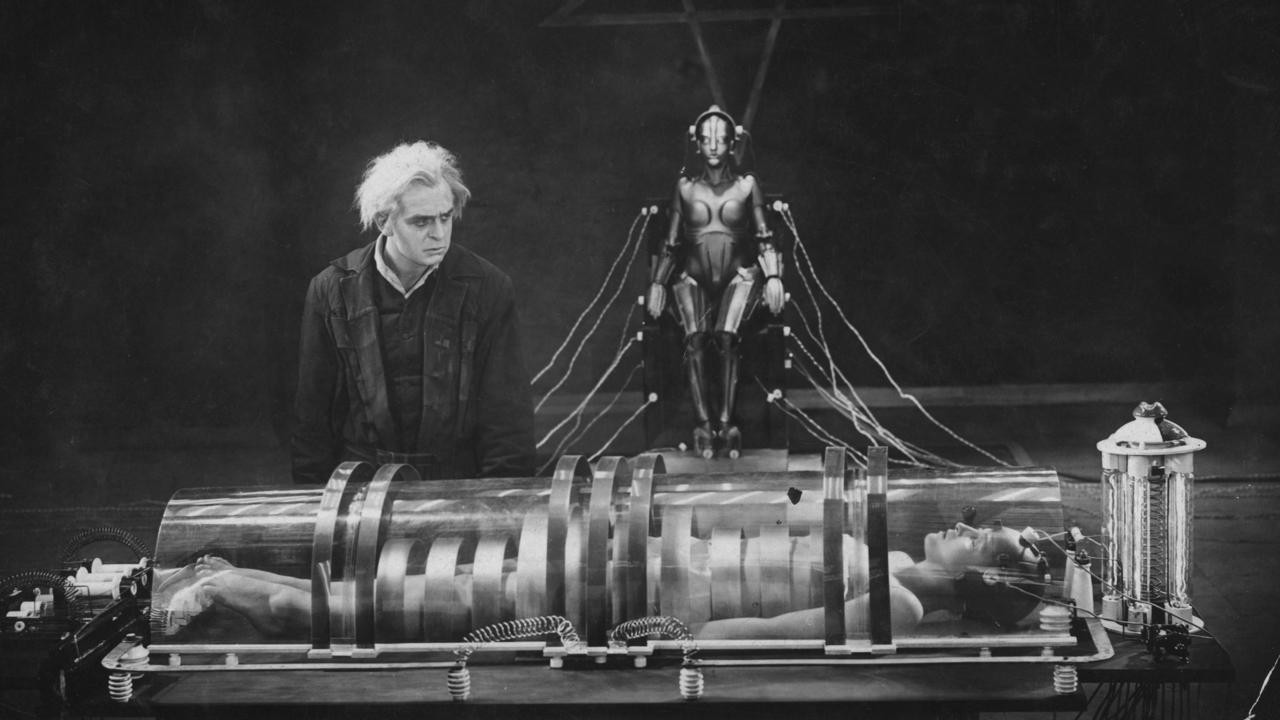

Sometimes art has content that suggests it belongs to a different medium. For example, the first film directors had a background in theater, and the movies they produced are often stunningly derivative of stage plays.

Watch a film from the 1920s and you’ll see lengthy static shots, minimalist editing, flat and declamatory acting, etc. Only in the middle period of Hollywood’s golden age did the techniques and approaches of film qua film emerge. Early films didn’t leave the vaudeville behind: they’re well made, but…they’re not exactly movies.

Romance of the Three Kingdoms is like that, but instead of being a play disguised as a movie, it’s a videogame disguised as a book.

More specifically, a strategy game. It reminds me of a six hour Age of Empires II game fought between skilled and stubborn adversaries amidst a mounting pile of energy drink cans. Battles without end. Thousands of men thrown into a woodchipper, often gaining nothing, or winning a victory that gets reversed minutes later. Numberless acts of heroism, which you see from God’s perspective and soon don’t even notice.

It’s about the fall of the Han dynasty and the three kingdoms (Wu, Wei and Shu) that ascended in the aftermath, trying to fill the power vacuum. They do this through a complex and Machiavellian mix of marriage, wizardry, and battles so bloody that it seems the population of medieval China gets slaughtered three times over.

The famous opening line “The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been” was not written by Luo Guanzhong, but was added centuries later. Nonetheless, it sums up his text: cyclical periods of destruction and renewal. Events are either meaningless or all-meaningful, depending on your perspective. There’s nods to “empty boat” style Taoist philosophy at times. The soil drinks blood. The soil then produces trees. The trees are used to make axes. The axes…

It’s hard to describe Romance without making it sound like the dullest book ever. It’s not. Nor is it the second dullest book. It’s actually interesting, once you crack the “code”.

The worst way to read it is like a traditional novel. Forget rising and falling action, dramatic climaxes, etc. Romance of the Three Kingdom’s intense moments come out of nowhere like monsoons, blow the lives of characters to pieces, and then end. Also, large parts are based on history, which is under no obligation to be satisfying to anyone. A better way is to view it like a growing plant: continually evolving in a way that’s no more and no less sensible than real history or the life of the reader.

And it’s thrilling. Despite the nihilism of the whole, you’ll still feel tense when Cao Cao fails in his plot to assassinate Dong Zhuo, and cheer at cunning method Zhou Yu uses to overcome an enemy fleet. Certain moments (such as the Battle at the Red Cliff) are as cinematic as Game of Thrones. And there are passages that would fascinate anyone with an interest in cultural anthropology and medical history. For example, the great hero Liu Bei’s reaction when he sees weapons inside his bridal apartment.

The bridegroom turned pale. Bridal apartments lined with weapons of war and waiting maids armed! But the housekeeper of the lady said, “Do not be frightened, O Honorable One! My lady has always had a taste for warlike things, and her maids have all been taught fencing as a pastime. That is all it is.”

“Not the sort of thing a wife should ever look at,” said Liu Bei. “It makes me feel cold, and you may have them removed for a time.”

[…]

Lady Sun laughed, saying, “Afraid of a few weapons after half a life time spent in slaughter!”

One wonders at what Luo Guanzhong is trying to depict here. Is Liu Bei suffering from what we today call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder?

The biggest challenging to climbing Mt Romance is the colossal cast of characters. To reach the end, you need to develop a sixth sense as to which characters are important to the plot and which ones will never be seen again. A lot of the characters have similar names. It can be hard to separate Zhang Fei from Zhang He. Maybe I’m a racist colonial paleface who thinks all Chinese names sound the same. But maybe not – Luo Guanzhong seems to be winking to the reader at times, such as in this (humorous?) scene where a woman vows to only marry a man with the same name as hers:

“Why did you trouble your sister-in-law to present wine to me, brother?” asked Zhao Yun.

“There is a reason,” said the host smiling. “I pray you let me tell you. My brother died three years ago and left her a widow. But this cannot be regarded as the end of the story. I have often advised her to marry again, but she said she would only do so if three conditions were satisfied in one man’s person. The suitor must be famous for literary grace and warlike exploits, secondly, handsome and highly esteemed and, thirdly, of the same name as our own. Now where in all the world was such a combination likely to be found? Yet here are you, brother, dignified, handsome, and prepossessing, a man whose name is known all over the wide world and of the desired name. You exactly fulfill my sister’s ambitions. If you do not find her too plain, I should like her to marry you and I will provide a dowry. What think you of such an alliance, such a bond of relationship?”

Romance of the Three Kingdoms might also be an early example of the Draco in Leather Pants phenomenon. The antagonist of the tale is clearly meant to be Cao Cao of the Wei kingdom, but he’s probably the strongest and most interesting character in the story, and a lot of people seem to view him in a positive light. Tumblr, of course, has an active community of Cao Cao stans.

But Romance isn’t a character study, it’s a videogame. The market seems to back this idea up. Usually classic works of literature attract a slew of movie adaptations, and maybe a single throwaway text adventure game made in 1984 by Infocom. But according to Wikipedia, Romance of the Three Kingdoms has been adapted to film eight times, to television twenty-four times, and as a game fifty seven (!) times. The book keeps rejecting its paper and clothing itself in binary. There might be three kingdoms, but ROTTK truly belongs in the realm of ones and zeros.

“I don’t like sand. It’s coarse, and rough, and irritating, and it gets everywhere,” – Albert Camus

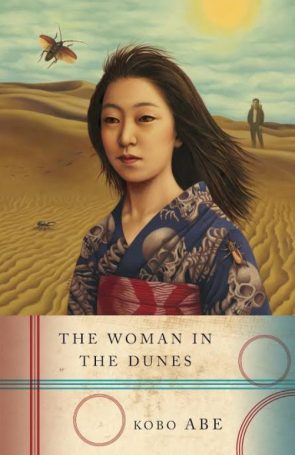

Western horror relies on convention – Bram Stoker’s vampires, Shirley Jackson’s haunted houses, and Romero’s zombies. By contrast, Japanese horror more often relies on free-standing symbols and images – Kôji Suzuki’s rings of light, Junji Ito’s spirals, and Shinya Tsukamoto’s metal sculptures.

Both approaches have strengths and weaknesses. Art rooted in convention is easier to understand: the audience automatically comprehends Slasher Movie #23532 in light of Slasher Movie #23531 (or the last one they remember). But it’s boring, and makes you a slave to the past: modern horror film is consequently a cesspool of spooky dolls and cars that won’t start and ghosts in mirrors and clanging ADR. By contrast, Japanese horror (at its best) achieves a monolithic starkness: I gave up looking for things like Suehiro Maruo’s Paranoia Star because I couldn’t find any.

The Woman in the Dunes is an eerie psychological novel about…sand.

An amateur entomologist is seeking a new kind of insect in rural Japan. He ends up trapped in a deep pit of sand. He has food and water and even female companionship (although she seems odd), but no way of escaping. This is not an accident. Someone just out of sight has planned this fate for him. He has a little shack that he spends hours each day sweeping clear of sand (uselessly; the wind blows it straight back in). He can’t contact anyone from the outside world. They’ll declare him dead and maybe they’ll be right to. His horizons are made of sand.

The Woman in the Dunes might not be a horror novel, as I don’t think Kobo Abe was trying to frighten. Kafka’s a better comparison. Nonetheless, I’m now aware of “ammophobia” – fear of sand. More specifically: fear of sinking into sand, swallowing sand, having sand grains between your toes, and so on. Just as Uzumaki left me uncomfortably aware of spiral shapes, I put this book down and was plagued by thoughts of sand.

It’s creepy stuff. Silken, fluid, deadly. Viewed under a microscope, sand is beautiful, but it’s inhospitable to human life, and defiant of mankind’s attempts to control it. You can sculpt a castle of sand on the beach, but the next day, it will be gone. But won’t the house you live in be gone someday, too? All of mankind’s buildings, on a long enough timescale, will become sand.

This is sort of how Kobo Abe’s protagonist rationalises his fate. The outside world is just temporarily rearranged sand and dust, so there’s no reason to want to go back. Being trapped in a hole is probably a privilege; he gets to see the truth. Ozymandias’s kingdom wasn’t overtaken by sand, it was sand.

There’s a livestreamer called Dellor who plays Fortnite and other videogames. He has a PO box, and if you mail him a package he’ll open it on stream. Occasionally, he receives sand. I’m not sure if a single person is behind this, or if it’s a shared joke among his fans. He’ll rip open an envelope, and sand will spray across his apartment. He gets keyboards with sand packed in between the letters. Once someone sent him an airsoft pistol with sand stuffed into the barrel. This annoys him, because (as the narrator of The Woman in the Dunes could confirm) sand is extremely hard to remove. No matter how much you vaccuum a carpet, in six months you’ll walk over it barefoot and feel the bite of a silica tooth: a reminder of our fundamental lack of control.

Western horror can be likened to a vine, which can be followed back to its root no matter where it goes, and J-horror to a series of mushrooms, which sprout out of the ground with no visible connection to each other. Or perhaps particles of sand. The Woman in the Dunes exemplifies the J-horror approach, even if it might not be J-horror. It has one idea. One single idea. It could have been written even if no other book had ever been published. It does not want to be the first book in the series, or to answer questions raised by another book, or to get adapted into a movie.

The Woman in the Dunes doesn’t even want to be entertaining (and frequently, it isn’t). It exists to exist. No matter what momentary order we impose on sand, in the end, it has no purpose other than to be sand.