This book arrived bedecked in heraldry as The Next Harry Potter (every children’s book released 2000-2005 was officially The Next Harry Potter, just as every modern David Bowie album was “his best since Scary Monsters”). It doesn’t live up to that, and doesn’t want to: it’s something else entirely. It hardly feels like a book for children. The action is fast and kinetic, the writing is as taut as the wire-work in a Hong Kong action film, and the concept is pretty clever: a mixture of Lord Dunsany fairytales and Die Hard.

The plot sounds outright stupid in summary: like it was created by a desperate screenwriter in the 8th season of a show. “There’s a twelve year old supergenius called Artemis Fowl, and he’s also a criminal mastermind, and has a scary bodyguard who kicks ass like Bruce Lee, and he discover fairies exist…wait, don’t go! They’re high-tech fairies! They have gadgets and guns! He kidnaps one and holds it for ransom, but then the fairies stop time, and…yes, I DID past the office drug test. Stop asking!”

But the book is better than its synopsis, too. There’s storytelling ideas at work here that I haven’t ever seen attempted before or since (even in the book’s own sequels). Want another book like Artemis Fowl? Go to your local bookstore, find the fiction section, look up “Colfer” under the Cs, and purchase Artemis Fowl again. Now you’ve got two copies, and that’s the best you’re going to do. Sorry.

The plot is essentially a kidnap and ransom story, but Colfer’s masterstroke is in the details: particularly centering the story on its villain. Later books would turn Artemis into a good guy: they soon devolved into repetitive, uninteresting capers where Artemis and his fairy pals go gallivanting off to bust the Villain of the Week, and I got bored of them. In the first book, Artemis is genuinely sinister and unpleasant, and a great character. Hell for the company.

Here (as in many places), the book takes cues from Die Hard: that movie developed its villain to the point where he stole the show – you wanted to find out exactly how Hans Gruber would pull off this ridiculous heist, with all the odds stacked against him.

Colfer kicks it up a notch by pitting twelve year old Artemis against a supernatural police force who can do anything from make themselves invisible to removing memories. Of course, the fairy police are as bumbling and bureaucratic as Die Hard’s LAPD, sometimes almost comically incompetent. And they are bound by magical rules – if they enter a dwelling uninvited, the instantly lose their magical powers. And when you’re a guest in someone else’s house, you have to obey the host’s commands. This makes life interesting when the host decides you can’t leave.

The book becomes a fascinating conflict between an almost omniscient race of fairies…and a really smart, really evil kid. That adds to the rising drama: it’s genuinely unclear who will win at the end, and again we see the necessity of Artemis being a bad guy. Nobody would write a children’s book where the hero loses. But a villain…?

Artemis Fowl has flaws (some of which would metastazise like a cancer and kill the later books in the series), and often succeeds more on shock and awe tactics than amazing writing. Tip: read it very fast. That way you won’t have time to think about the finer details.

Details such as how the fairy cops are called the Lower Elements Police Recon, or LEPrecon (leprechaun!). That gets a laugh, but why do fairies use English words, when they’re explicitly described as having their own language? And how did “leprechaun” (a word dating back to the 17th century), come from “recon” (a military abbreviation of “reconaissance” that apparently dates back to the 1940s, if Ngram viewer is correct)?

Artemis apparently possesses magical powers of his own, such as when he uses a household magnet to unscrew a screw (magnetic torque can’t operate on a uniform substance such as a metal screw). This is also one of those books where a character translates a text in an ancient language, and it comes out in perfect rhyming English couplets. Sometimes Colfer just loses track of his own rules. A “bio bomb” is described, which explodes and turns living tissue into “a cloud of radioactive molecules”…but a group of characters journey into the fallout zone of one expecting to find bodies.

The Artemis Fowl books never gained the mass fame of the Harry Potter series. In my opinion, they’re collectively not as good. Harry Potter had an arc that continued from book to book, but Artemis Fowl didn’t even feel like it needed a sequel. The premise was fully explored, and afterwards there was nowhere left to go. The kid-friendly trappings held it back a bit: it feels like a story for grown-ups at its core, and it would have been improved by a bit more of an edge. Marketed wrong, promoted wrong, and developed wrongly by its own author, in isolation Artemis Fowl is an extremely good piece of work.

Action, adventure, and uncomfortable ethnic stereotypes; The Story of Dr Dolittle has everything you could ever want in an early 20th century children’s book.

The book (and the series that follows it) features a scatterbrained doctor with the ability to talk to animals. The first two or so Dolittle books follow a strict format: John Dolittle goes adventuring, gets into trouble, animals rescue him in a funny or interesting way, all of this happens again about ten or fifteen times, the end. Hugh Lofting soon grew in sophistication as a writer, the later books tend towards singular stories with allegorical themes. These often focus entirely on animals, dropping Dolittle out of the picture entirely.

There’s surprising philosophical acuity to Dr Dolittle. Wittgenstein said “If a lion could speak, we could not understand him”, and Hugh Lofting plays with this idea: humanity is cut off from the animal world by language, and this represents our failing. Who says animals don’t talk? Have you heard how incessantly birds chatter? How much dogs bark? Animals are always talking, constantly sharing thoughts and ideas, and we aren’t listening. The Dolittle books can be didactic on this subjects, and the latter ones feel written by a temporally displaced PETA activist. Often they verge on expressing outright contempt for humanity.

We have a good guess as to where Lofting’s antipathy comes from.

The Dr Dolittle tales started out as letters, scribbled and sent home from the trenches, and the author’s wartime experiences hang over the Dolittle tales like a flag’s shadow: never touching the story, but always present. The Great War was a bad one, industrial revolution alchemizing the battlefield, and a generation of young men witnessed entrails slithering out of bullet and bayonet wounds, faces melted by mustard gas, and mobile hospitals where the shrieking never stopped and the ground stank for weeks after. In the midst of this, Lofting was struck by the gallantry of horses and mules, and was embarrassed at how little his fellow men could do for them. He created John Dolittle in retribution, a physician who could give them the medical attention they seldom received in real life.

Other writers for children – JRR Tolkien, AA Milne, CS Lewis – also served in the war, and were influenced in various ways. Tolkien rejected modernity. Milne tried to wallpaper over reality with fantasy and whimsy (is it disturbing that he named his son “Christopher Robin”?). CS Lewis retreated into spiritual nihilism: nothing matters because the world shall soon dissolve like snow; the sun forbear to shine.

Lofting became a misanthrope. He believed, at the end, that humanity was a mistake, that we do not deserve our place on the planet. As the Dr Dolittle books progress, they get blacker and angrier, increasingly given to polemics about the irredeemable evil of humanity. I never finished Dr Dolittle and the Secret Lake, it was wearisome and depressing. Lofting’s disgust becomes a suffocating hand, strangling life from his stories. But that’s many decades away. The Story of Dr Dolittle is fun, with barely a hint of future despair.

As with most good children’s stories, it invites you to take it seriously and ask questions about its world. For example, when does the story take place? The opening passage says that it happened “when our grandfathers were little children”, and the parrot Polynesia (who claims to be either one hundred and eighty one or one hundred and eighty two years old) describes seeing King Charles II hiding behind an oak tree, an event that happened in 1651.

This dates the book to no later than 1832, and makes aspects of it anachronistic – John Dolittle wouldn’t be able to vaccinate the sick monkeys, for example. There’s clues that the book might be set even earlier – the doctor is menaced by Barbary pirates, who had been pacified for over fifteen years by that time. But that would throw still more story elements out of date: such as an Italian organ grinder with a monkey (which is an artifact from the 19th century). The monkey in question later tells stories passed down by his ancestors about “…lizards, as long as a train, that wandered over the mountains in those times, nibbling from the tree-tops.” This was interesting. People in 1920 knew about dinosaurs, but didn’t know they lived in a different time to primates.

Something should be said about the story’s…uh, racial complexities. In short, John Dolittle ends up at the mercy of an African tribe, whose prince, Bumpo, wishes to become a white man. In return for freedom, the ever-resourceful John Dolittle uses medicine to bleach the prince’s face.

Make of that what you want. My two krugerrand: Bumpo is a strange man and his desires are clearly depicted as abnormal in the story (one character calls it a “silly business”, and another states that he looked better as a black man). And given that skin-lightening is now an industry worth tens of billions of dollars (with over 70% of Nigerians using some sort of skin-lightening product, according to WHO), a desire for paler skin clearly isn’t an idea that sprung wholesale out of Hugh Lofting’s evil, racist brain.

The book’s imaginative, but sometimes I wish it went a little further. The episodic “adventure / problem / escape” format can get repetitive, and there’s fascinating possibilities left unexplored. Long chunks of the book involve the doctor trying to bring a rare beast back from Africa – a “pushmi-pullyu”, which has a head at each end of its body (there’s an argument that Dr Dolittle inspired Nickelodeon’s Catdog). The Doctor plans on exhibiting the animal as a sideshow, thus saving himself from financial ruin. One wants to yell at him “You can talk to animals! There are thousands and thousands of ways you could become rich! Use mice to steal the crown jewels! Use paper wasps make casts of the locks to the Bank of England! Use dolphins to patrol the sea floor and find sunken treasure!” If the Doctor wanted to, he’d be running the British Commonwealth within twenty years.

But those goals would be amoral. John Dolittle is so saintly he’s boring, and I wish he had a Moriarty: someone who shares his zoolinguistic powers but uses them for evil, not good.

The Dr Dolittle series enjoyed a good run, but it doesn’t seem to be remembered alongside Winnie the Pooh and Alice in Wonderland. Do the racial elements make the books unsalvagable? That would be a shame. In 1998 it was loosely adapted as big budget Hollywood comedy starring Eddie Murphy, and again as an accidental comedy starring Robert Downey Jr. No doubt it’s being reprinted inside plague bags lest innocent bystanders be infected with racism or something. Buy it however you can find it.

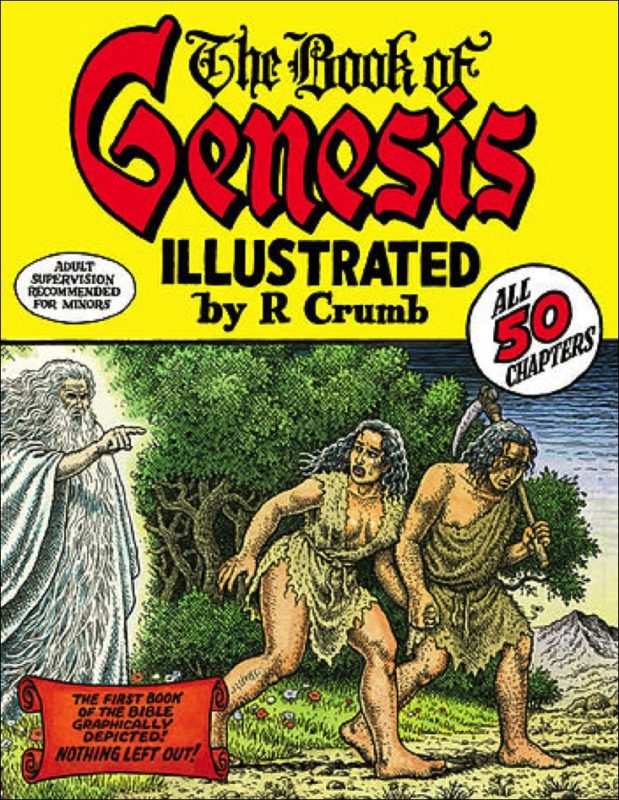

The Book of Genesis is a 224-page graphic novel by noted cartoonist Robert Crumb, based on the book of the same name by noted deity God. It’s literally the full text of Genesis, painstakingly hand-lettered in (and around) cramped panels of Crumbian imagery. It’s all here: the famous stories, the less famous stories, and even the “Jokshan begat Dedan, who begat Ashirum, who begat…” genealogies. Not a verse has been cut, no matter how boring or inappropriate for the comic medium.

Nothing like this has been done before, and hopefully nothing like this will be done again.

While reading The Book of Genesis, a nagging issue kept bothering me. The point. Where is it? What is it? What is any sort of reader supposed to get uot of this? Crumb spent four years working on a product with no entertainment value at all. Maybe he feels pride in being the first person to adapt Genesis unabridged as a comic book, just as the first astronaut to land on Pluto will feel pride, despite it being a dull lump of rock.

So why doesn’t it work? Biblical-themed comics tend to either be didactic, cloying efforts by believers (Jack Chick’s tracts being the most famous example) or angry polemics by atheists (see Jesus and Mo and a thousand other webcomics). I assumed Crumb – who has perfected body duplication technology so that he can be a fly in every jar of ointment – would be in the second group, and that the Book of Genesis would be full of gleeful blasphemy.

Instead, it’s exactly what I’ve described: a comic version of Genesis. Not a single other adjective applies – perhaps not even “good” or “bad”. This is a huge problem: the stories of Genesis are so familiar and famous that artists have stripped them to their bones. If you’re attempting to tell (and sell) the tale of Noah’s Ark or Jacob and Esau once again, you damned well need a second adjective!

Despite doing the art, Crumb leaves no trace of himself in the book. Does he like the stories he’s writing down, letter by letter for fifty straight months? Does he hate them? What emotions do they inspire? Is he realizing any spiritual truths? Is he growing even more sure of his decision (at age sixteen) to become an atheist? I have no clue. I’m not Crumb’s biggest fan but I understand why he’s liked: he has a style, and it’s a compelling one (nobody else could have written Fritz the Cat, for example). But he approaches this project with all the verve of a manga letterer making a thousand yen a page. There’s no creative elan to be seen here.

His imagery is trite, cribbed from Michelangelo, Ignatius of Loyola, and Cecil B DeMille. God has white hair and a beard. He creates the earth like a wizard casting a spell in a Saturday morning cartoon. The Garden of Eden looks like Bambi. The Ark is a large floating shoebox. There are some unintentionally funny parts. During the genealogies, he needs to come up with a visual element, so he just draws headshots of what these dozens of people might have looked like. It looks like the fighter select screen in an SNK fighting game.

Crumb’s form constantly works to undercut him. The Bible’s stories are big and epic, and they would have benefited from double-page spreads, not tiny panels. Again, there’s unintentional laughter. During the flood, we see drowned people and animals, floating face-up in the boiling sea. It would have been a striking piece of art, except it’s too small. They look like toys bobbing in a child’s bathtub.

If I could guess at Crumb’s purpose, it was to provide a comic that contains no exegesis or interpretation whatsoever. The mere act of editing a work, by definition, changes it, so by leaving everything in, he was free from the charge of distorting the Bible. However, Genesis is quite a long book, and cramming it into a comic makes it virtually unreadable. So much text crowds the page that it induces claustrophobia. Combined with Crumb’s signature art style (itchy, hairy, and uncomfortable) and you have one of the most unpleasant experiences I’ve had so far in a graphic novel.

Occasionally, he takes a few small liberties. Potiphar’s wife is depicted as a harridan, not remotely beautiful. The city of Sodom is obviously (and anachronistically) Babylonian, with Ishtar Gate inspired architecture. The passages at the end where Crumb discusses some of the stories are quite interesting, but again he keeps his feelings close to his chest. And that’s something nobody wants to see from Crumb.

The Book of Genesis is a little like a sculpture of the Brooklyn Bridge made of toothpicks, more interesting for its existence than its function. “For verily I say unto you, till heaven and earth pass away, one jot or one tittle shall in no wise pass away from the law, till all things be accomplished” (Mt. 5:17-18). Well, it’s been accomplished. And now I will move ahead to never thinking about it again.