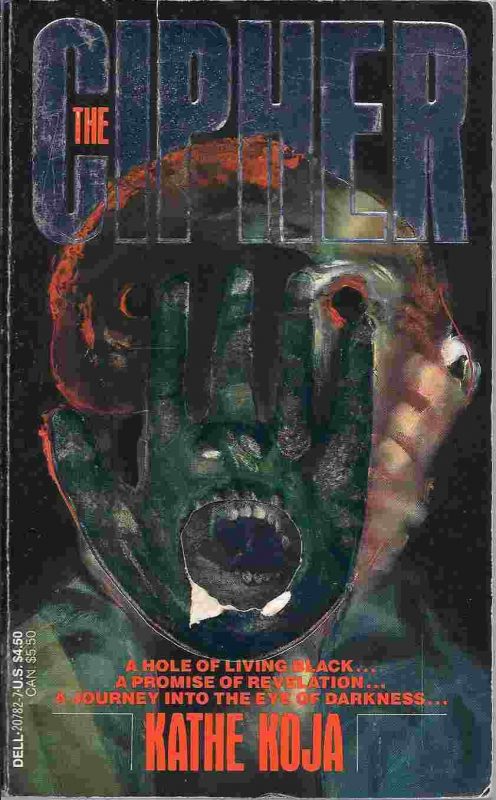

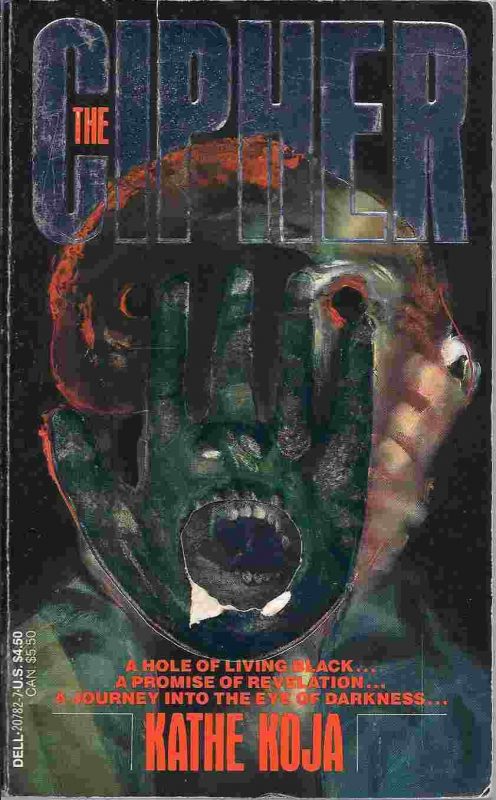

Horror novels have a shelf life of forever or five years, whichever comes first. Kathe Koja’s first novel The Cipher was published in 1991, won the Locus and the Bram Stoker, was critically acclaimed as a major work of the genre…

…and then went out of print for thirty years.

It has a sharp premise. Failed poet Nicholas (and his codependent girlfriend Nakota) find a black hole in storage cupboard. They begin dropping things into the hole on a string. Bugs grotesquely mutate into chitinous aberrations. A dead mouse turns into a Jurassic horrorshow with claws twice the length of its feet. Then they lower a camera into the hole…

The Cipher belongs to the micro-genre of “hole fiction”, which includes Stephen King’s From a Buick 8 and Junji Ito’s The Enigma of Amigara Fault and others I can’t recall. A fracture appears in reality; one that cannot be understood, only experienced. Things transform when they pass through it. The “holes” in these books are never actually holes, they’re a metaphor for some writerly stalking horse (the unexplainable, death, and so on). Early on, Nakota makes the observation that the Funhole (as they call it) only becomes active when Nicholas is around it. Why would this be true? What’s special about him?

Koja’s prose is striking. Her patented “kill all verbs” style shatters sentences into oblique, slanted observations, which collectively pile up into scenes, action, etc. Koja’s sentences are frag grenades, in both senses.

We waited quite a while, there in the dark, my back against the locked door, Nakota for once at my side. Her scent was higher, her breath never slowed; she tried to smoke but I told her no, not in that airless firetrap, firm whisper, as firm as I ever got with her anyway, and she gave in. The insects jumbled, up and down, fighting the barrier they couldn’t see, then, “Look,” her sharp whisper but I was looking already, staring, watching as the bugs, one by one, began to drop, dying, to the floor of the jar, to whir in minute contortions, to, oh Jesus, to change: an extra pair of wings, a spare head, two spare heads, colors beyond the real, Nakota was breathing like a steam engine, I heard that hoarseness in my ear, smelled her hot stale-cigarette breath, saw a roach grow legs like a spider’s, saw a dragonfly split down the middle and turn into something else that was no kind of insect at all.

Koja, more than any author I’ve read, writes the way people see. We perceive vision as continuous, but it’s actually made up of thousands of micro-adjustments called “sacchades”. We flick from thing to thing, and gradually a picture of our surroundings emerges. It seems instantaneous, but it’s more like a painter’s process. One brushstroke. Two brushstrokes. The Cipher’s style is an effective evocation of this process.

The setting’s a grimy urban environment, with dirty snow, broken central heating units, rust, and dying video stores. Koja’s big on art in all its forms, and stuff like cinema and sculpture appear in the story, to varying impact.

Not all the story choices work, and The Cipher ends up being more good than great. After some fantastic early scenes, the momentum falters. A couple of new characters get added who don’t seem particularly relevant but succeed in padding the book out for another 100+ pages. The problem with elegant concepts is that it’s hard to get a novel out of them. The Cipher would have hit harder as a novella. As it stands, it has a stretched quality. Like a 4:3 video stretched to 16:9, or a 45rpm played at 33rpm.

edit: I have since learned that The Cipher was adapted from a work of short fiction, which makes sense.

The shocks (which are initially powerful) become increasingly broad and heavy handed, and verge on comical at a point. There’s moments in the book that read like a Chucky screenplay. They don’t ruin things, but the narrative felt like it needed a subtler hand at times.

Koja’s later work is more confident. Bad Brains shows the umbilicus chaining artistic ambition to madness (and vice versa). Skin documents a world of metal and gears where carbon-based lifeforms fear to tread. But The Cipher has its own charms: it’s very visual for a book, and would work well as a movie. Ironically, because Nicholas is doomed from the moment he begins filming the Funhole.

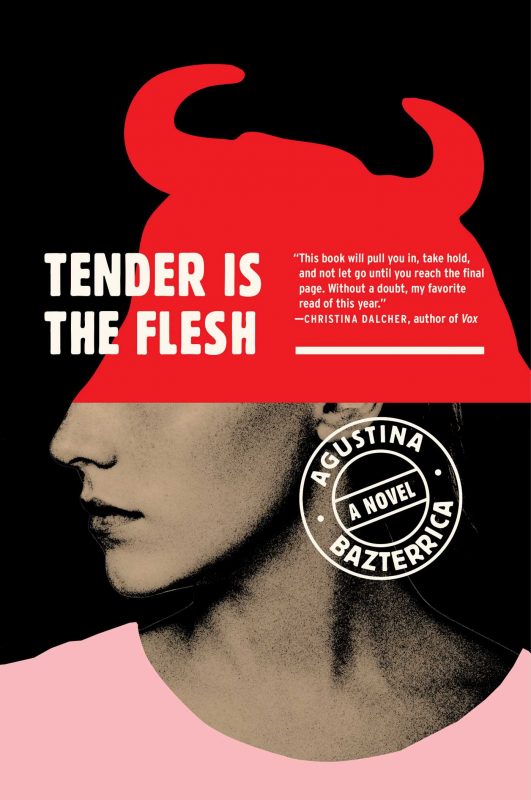

A lumbering parable that asks “what if we used humans as livestock?” A provocative question that has never been asked before, except in A Modest Proposal and Soylent Green and Sweeney Todd and The Road and…

Marcos works at a processing plant for “special meat”, ie, people. An infectious plague has rendered all animal meat poisonous, and the government (through euphemism and bureaucracy) has legalized cannibalism. Most of his book involves Marcos going about his daily life while feeling sad.

The book never gets out of its own way. It’s so certain that it has a great premise that it never moves past that premise and does anything with it. Marcos is a flat and uninvolving character. The endless quotidian detail of his job just provokes a response of “Yeah, eating humans is horrible and awful. So what?”

I suppose the book is intended to shock us awake about the horrors of factory farming, or whatever. It’s a thought experiment often advanced by environmental ethicists. “How can you be comfortable eating a cow but not a person?”

For the same reason I’m comfortable driving over asphalt but not a person. Asphalt isn’t people, and neither are cows. The parable falls apart for me because it comments on a real life issue in a way that distorts the issue beyond recognition.

Moral philosopher John Rawls proposed that ethical decisions be made behind a “veil of ignorance”. Imagine you’re a baby that’s about to be born. You don’t know anything about who you’ll be, or your circumstances, or anything. You might be a king or a pauper. In light of this, what world would you like to be born into?

Specifically, would you want to be born into Bazterrica’s world? I wouldn’t: I might be special meat and suffer any number of horrible experiences. But suppose Rawl’s veil of ignorance crossed the species barrier. You might be born as a human, or born as a cow. Would you like to exist in that world (ours)?

The thing is, I can’t imagine life as a cow. Do they experience pain? Certainly. Is it the same pain as ours? I don’t know. Are they conscious? Probably. Is it a sort of consciousness where they can anticipate the future, feel regret, imagine different circumstances, and so on? I don’t believe so. These are questions Tender Is The Flesh doesn’t get around to answering. Most people object to factory farmed livestock because the animal suffers in the process, but raising humans as livestock would (to my view) be morally wrong even if the human didn’t suffer, because you’re infringing on the will of a highly conscious being. You can’t swap animals with humans in this scenario, the whole equation changes.

Bazterrica’s world needed a stronger sense of realism. Instead, it comes off as fantasy, totally disconnected from our world, less A Modest Proposal than Gulliver’s Travels. The scenario makes little sense. Nobody would raise humans as livestock even if it were legal to do so. Humans are strong, intelligent, and capable of communication and using tools, all of which would make them extremely dangerous to their captors. Worse, they take fifteen to twenty years to reach maturity, during which time they must be fed millions of calories. How could that be economically viable? I think if meat became inedible we’d start meeting our protein needs with things like soy instead.

The inciting incident is that Marcos receives a female human as a gift-slash-bribe. He’s supposed to eat her. He develops feelings for her instead, and eventually impregnates her, (ironically) a major crime. I was reminded of something I saw on Reddit. If Elmer Fudd was trying to rape Bugs Bunny, it would be horrifying. Luckily, all he’s trying to do is kill him.

This is another big moral issue: pets. We have furry animals in our homes that we consider part of our families. But on a certain level, this is more manipulation. They’re there to fill selfish emotional needs. Thousands of dogs get abandoned once they’re no longer cute puppies, and even well-cared for animals are living a life they weren’t designed for. There’s an argument that keeping a big dog in a suburban apartment is as wrong as raising a cow in a feedlot. This was the stronger side of the book for me.

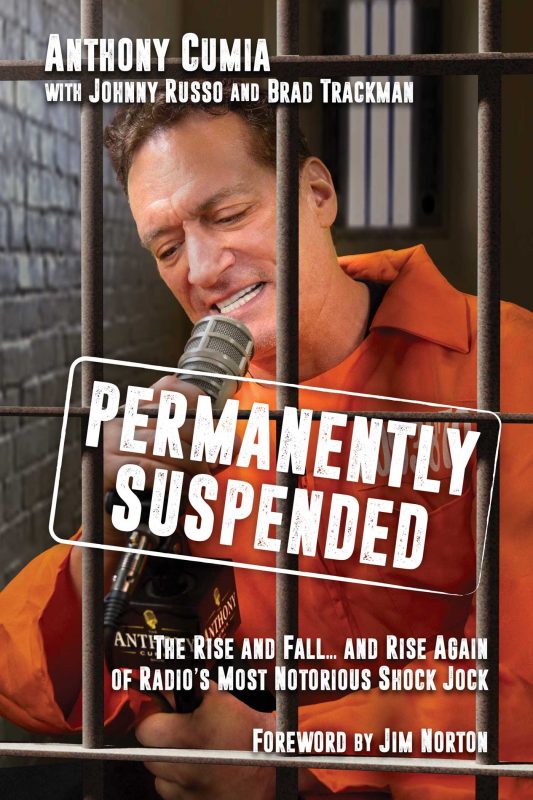

They used to make these little boxes where you’d jiggle a dial and someone’s voice would come out. The voices belonged to radio jocks, who were in constant competition for listeners. Some had smooth voices, some played the right music, others had the “local perspective”. Then, in the late 80s, they started saying naughty words.

“Shock jock” radio hit its peak in the 1990s. The usual format (used by scores of stations) was two guys with a line in outrage, dodging fines and performing increasingly outrageous stunts. It was a simple, effective storyline with ready-made heroes and villains: the plucky, scrappy radio DJs (yay!) versus the big bad “management” entity that was always trying to ruin the fun (boo!). The FTC enforced strict content guidelines for public airwaves, and it was a game to see how far jocks could take edgy content. You almost had to keep tuning in: it might be the last day your favorite show was on the air.

Opie & Anthony were a shock jock duo of exceptional quality. They achieved success (in between repeated firings and cancellations) as a kind of everyman Howard Stern show, doing a mix of stunts and pranks and gross-out bits. They weren’t afraid to lampoon the radio business itself – their “Jocktober” bits were quite revealing as to how fake and constructed almost every part of a commercial talk radio show is. In their later years they transitioned to being a proto-podcast, focusing almost entirely on interviews and nonscripted content.

This new focus on personalities made something clear: one of the hosts was way more talented than the other.

Gregg “Opie” Hughes had gone to broadcasting school and knew how to push buttons and go to segues. But Anthony Cumia was a dementedly funny, with thousands of fascinating stories, a skill at impressions, and an ability to “rap” with almost anybody. He was self-destructive (a race-rant got him sacked from his own show), but was ridiculously skilled at what he did. The crosses in his backyard weren’t the only thing on fire.

Or as Jim Norton says:

“Regardless of the discussion, the context, the topic, Ant has the ability to reach in with perfect timing and pull out something funny. He is by far the most talented radio performer I’ve ever known, and he’s as fast as any comedian who has ever lived. I’m a great get if you nee someone to describe an old lady falling down the steps or a blumpkin joke, but Anthony can be captivatingly funny describing air-conditioning duct installation. He can walk you through every aspect of the most monotonous activities, paint a perfectly clear picture, hilariously veer left and right, and will not once stray into the territory of boring.”

Permanently Suspended: The Rise and Fall… and Rise Again of Radio’s Most Notorious Shock Jock is Anthony’s biography. Disappointingly, it has coauthors. Indeed, large sections read like one of Anthony’s broadcasts transcribed. It basically covers his life from childhood to 2017 or so, when he was hosting a show with Artie Lange (which he no longer does). I’m not sure who it’s for. Non-O&A fans won’t care. O&A fans will have heard all of these stories told before on the radio, many times. But it’s funny and fast-moving, and there are lots of photos.

I found the hardscrabble early O&A years particularly interesting. Again, most of it you’ve heard, though it’s good to know that Ant’s hatred for WAAF program director Dave Dickless continues unabated.

This Dave Douglas guy was always just a bug up our asses. He once said, “You know what you should do? Take a picture of who you envision as an audience member. Who do you picture? Find a magazine with a picture of someone who resembles this person you have in mind and put that picture in front of you on your mixing board. So when you’re talking into the mic, you get an image of who you’re talking to.” The fucking guy actually said this! Well, we nodded and smiled, and I couldn’t look at Opie and he couldn’t look at me at this point. We were just laughing our fucking asses off. […] Then we found a Swank magazine and cut out pictures of a woman squatting and posted the pictures. “Here’s how we picture our audience: a bunch of filthy cunts.”

The book captures Anthony’s head at a particular moment, when he’s immersed in his current gig, and that weights the book in a way I didn’t care for. Reading about a millionaire building a studio in his Long Island mansion is boring. And there’s obviously a lot of juicy drama that he leaves out – stuff like his fling with transsexual Sue Lightning that you’d only know about from the now-banned subreddit.

Anthony has zero business skills (as he admits himself), and his career has been spent waiting for lucky breaks. But in the long run, nobody in radio was that lucky. In 2000, satellite radio emerged as a commercial force. Because it didn’t use the FTC’s airwaves, it could be completely uncensored. Everyone thought that satellite would be God’s gift to the shock jocks: instead, within a few years the format had been killed forever.

Why? It turns out that shoving a wiffle bat up a female intern’s fundamentals was never that funny (particularly when you couldn’t see it). It was interesting because of the shock: you weren’t allowed to do stuff like that on the air! Once you were, the shock disappeared, and the whole enterprise stood revealed as boring and hack.

The book is bittersweet because it records an era that will never come again. The mid 90s exist in a cultural gray zone of sorts: too late to be lionized like the 60s, too early to be effectively archived by the internet. Shock jockery is the kind of thing that was once everywhere, but now mainly exists in memory. Anthony Cumia is a graying part of a once-great legacy.