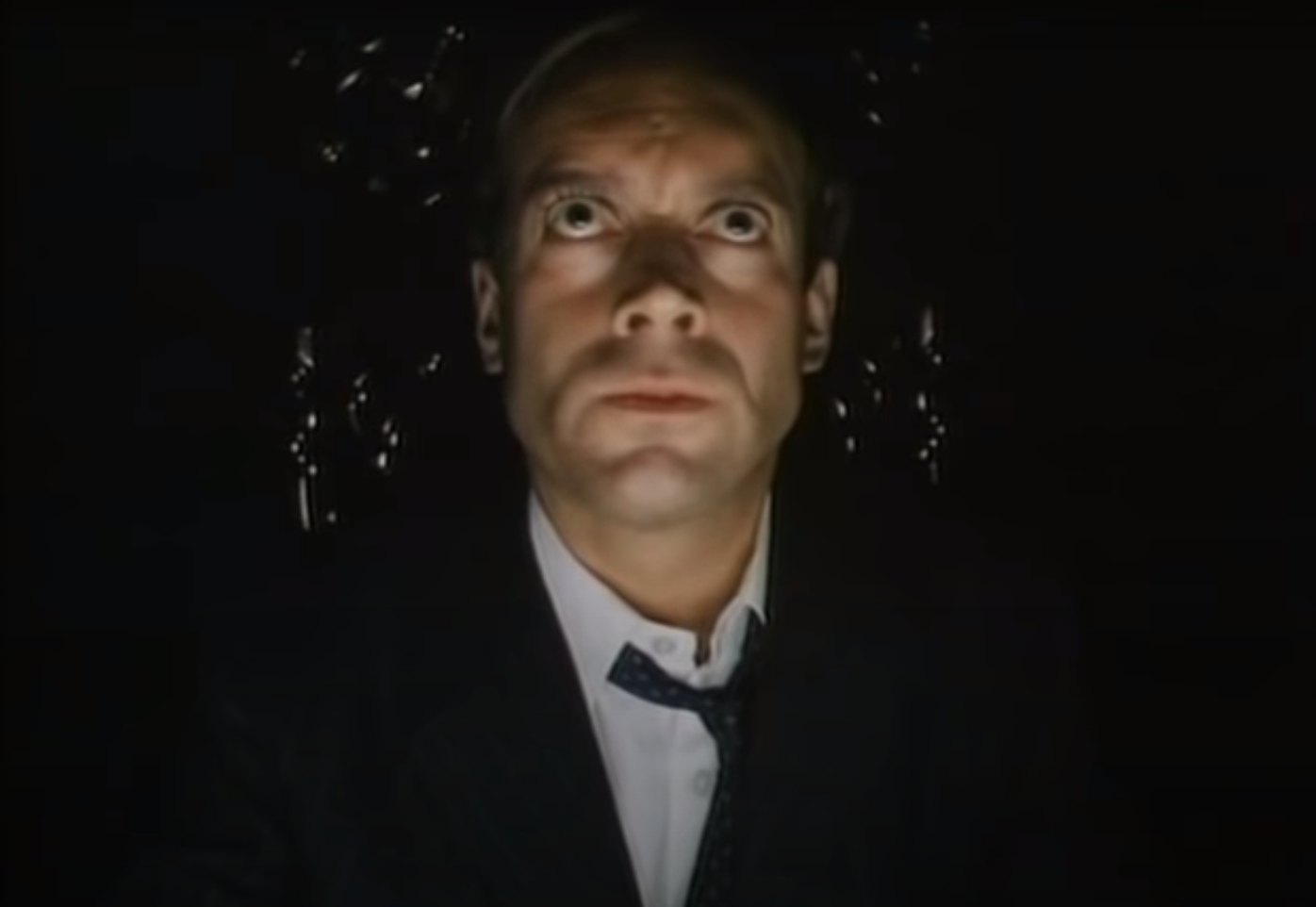

Max Headroom is a “computer animated” TV host from the 1985 UK music video series The Max Headroom Show, the 1985 telemovie Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future, and the 1987 science fiction series Max Headroom.

Air quotes because he’s not computer animated, he’s actor Matt Frewer with latex and foam stuck to his face. Computer animation cost tens of thousands of dollars per minute in 1985, and Victorian chimney-sweeper logic kicked in: “screw cutting edge technology, let’s send an eight-year-old boy up the flue.” In 2020, computers steal jobs from humans. In Max Headroom‘s time, we stole jobs from them.

Max’s character is jarring and wrong, st-st-stuttering like a stroke victim as he reels of Dangerfield-esque one-liners. The idea is that he’s a human consciousness digitized imperfectly – a half-a-human. You can’t be at ease while watching him, it’s like eating dinner off a cracked plate. The fact that he was broken ironically made him complete: nobody would remember his unfunny jokes if they’d been delivered in a normal voice. He’s a vivid example of glitching and ugliness used for artistic effect (note the similar stuttering used in Paul Hardcastle’s “19”).

Max is a one-idea character, but the idea proved highly successful. He’s widely recognized (and parodied). There’s a Hello Kitty aspect to Max: everyone recognizes the character, but few can tell you where he’s from, or even where they first saw him. For some, it was the New Coke commercial; for others, Max Headroom just exists, a creation without a creator, floating freely in conceptual ether.

The character, however, emerged out of a very specific set of circumstances.

In 1981, video killed the radio star, and stations such as MTV needed hosts to talk between records (where “talk” means “sell products”). Unlike radio hosts (who were heard but not seen), video jockeys needed to look attractive, or at least interesting in some way. They couldn’t, for example, be a man “shaped like whatever container you pour him into” (in Patrice O’Neal’s immortal roast of chubby radio host Jim Norton).

Most stations wanted their hosts to be hip, the UK’s Channel 4 took a different path and made their host a weird, uncool goober, whose lame one-liners are further mangled by a layer of digital distortion.

It was a great idea: Max Headroom won’t ever become lame: he’s already maximally lame. He won’t lose dignity when he plugs a sponsored product: he had no dignity to begin with. Rock stars will want to talk to him: he’ll made even the most incompetent cokehead seem like a scholar.

But Max Headroom didn’t become famous from the music video show.

It soon occurred to Channel 4 that this character might work in a sci-fi drama, and the result is a dated but interesting cyberpunk film that owes a lot to Blade Runner and Brazil, although made for far less money.

The film is set in near-future England, which could be described as “Thatcher, but more”. London is as black and filthy as the inside of a tar-saturated lung. Thugs lurk in the shadows, ready to kidnap you and sell your organs to body banks. Industry is ferocious, a terrifying machine running on a fuel of human lives. There are televisions everywhere, blaring idiocy.

The plot involves entertainment conglomerate Channel 23, who have invented a new form of TV ad called the “Blipvert”. Traditional 30-second ads annoy viewers and cause them to change the channel, but Blipverts allow ads to be compressed into a few seconds of high-intensity audiovisual stimulation. Ratings are through the roof. However, some people experience a side effect: they explode.

There’s some funny and effective satire where we see Channel 23 execs trying to defend Blipverts. No causal link has been proven! Surely some percentage of the population can be expected to randomly explode, right? Also, if you explode after watching an ad, isn’t it your fault in the end? We’re probably supposed to think of tobacco companies: modern viewers will think of the oil industry.

Regardless, star reporter Edison Carter (who works for Channel 23 himself) gets “too close to the truth” and suffers a tragic motorcycle “accident”. However, he’s supposed to appear on air later that day, and a bungled attempt to digitize Carter’s brain results in an odd lifeform that immediately utters the words “Max Headroom”, because that was the final thing Carter saw before his bike crashed.

Writer George Stone says British firms spent millions of pounds relabeling the “Max Headroom” signs in public garages to “Maximum Height”, due to association with the character. There’s a slight chance that Max Headroom actually cost Britain more money than it made.

The movie did not really have a budget. Its portrayal of futuristic London as an industrial wasteland is more a concession to lack of money than anything (in a stroke of luck, they were able to shoot in Beckton Gasworks, where Stanley Kubrick filmed certain scenes in Full Metal Jacket).

Yet it nails the things that are cheap: acting, and tone. A grungy and effective mood soon appears. The story’s confusing and hard to follow, but it’s not boring.

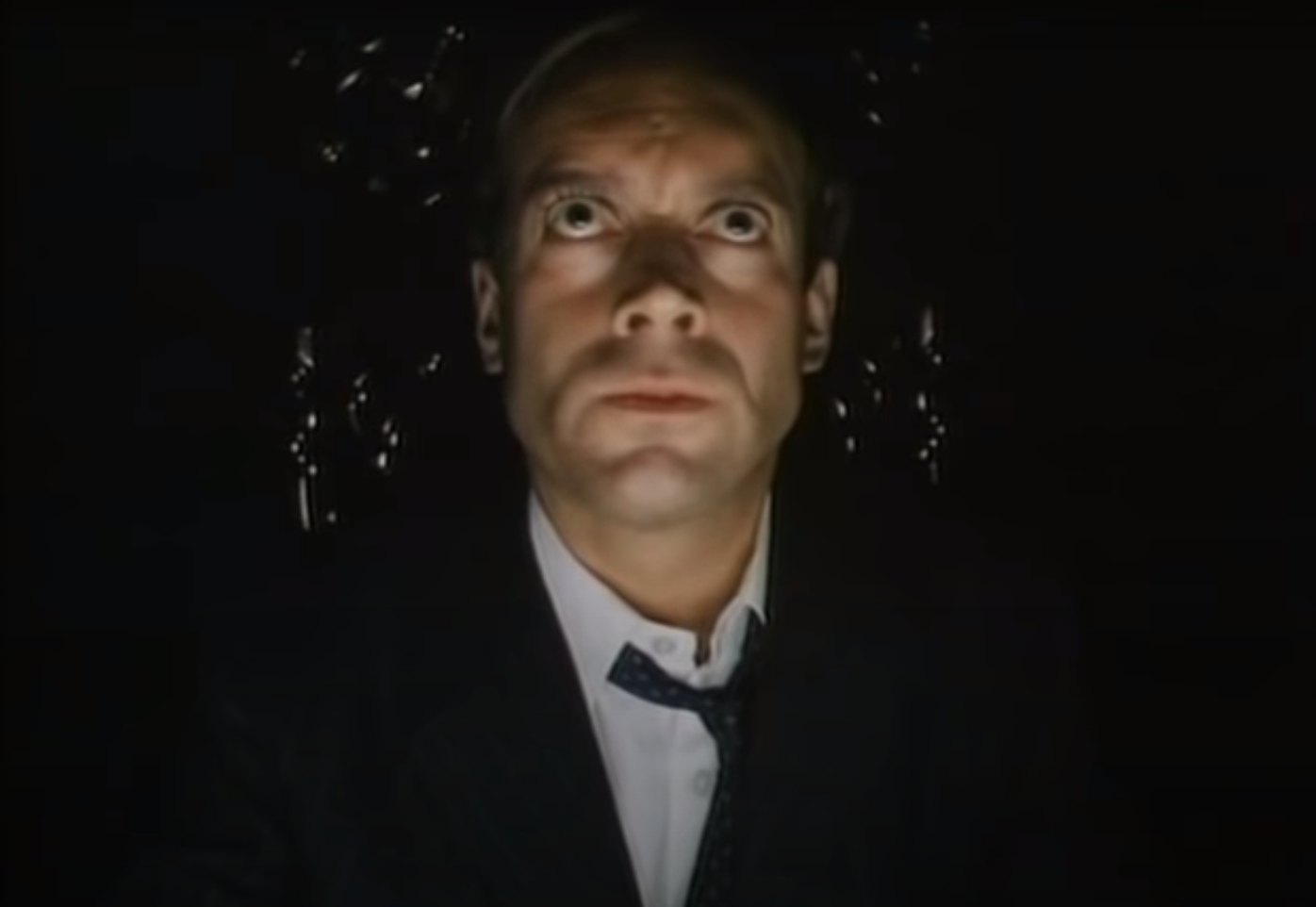

The camera-work has an aggressive, edge-pushing quality that’s as unsettling as Max Headroom himself. For example, consider the alarming way the villainous Channel 23 head Grossman is framed. Sharply underlit, and distorted by bubbled lensing in a way that emphasises actor Nickolas Grace’s exotropia. He looks terrifying, a one-man Panopticon.

Max Headroom actually doesn’t do much in this movie. The same holds true for the American TV series: the episodes explore some science fiction conceit related to capitalism and media (a reality TV show is attracting viewers through subliminal mind control, or something), and Max serves as a framing device for the story. He’s Tel-vira, Maxtress of the Byte. But isn’t that what a VJ is supposed to do? Introduce stuff, and get out of the way?

People like Edison Carter and Theora got to have all the fun, running around and solving crimes. Max is just a talking head, frozen in place, transfixed like a glitching, jittery butterfly upon a technological pin.

He has nothing to do. He just tells his idiotic jokes and becomes more outdated day by day. Matt Frewer was wont to complain about how annoying his makeup and prosthetics were (“like being on the inside of a giant tennis ball”), but the character itself was just as restricted.

Video hosts are passive, powerless ciphers, introducing the action without ever being a part of it. They’re like eunuchs guarding the sultan’s harem – yes, they know all about the deed, but they’ll never do it for themselves. It’s no surprise that the career breeds dissatisfaction, and a search for something more.

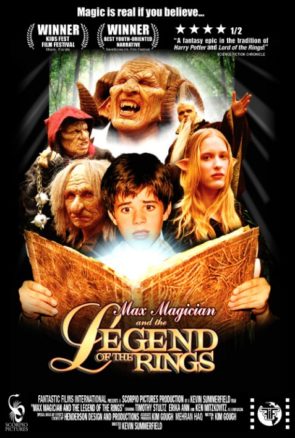

A “mockbuster” is a low-budget ripoff of a famous movie designed to trick you (or more likely your grandmother) into buying it. Major Hollywood films can have print and advertising budgets in the range of hundreds of millions of dollars, and just like harmless moths copy the markings of venomous wasps, a well-designed fraud can exploit another movie’s publicity blitz without spending a cent in advertising itself. A rising tide lifts all boats, but it also lifts turds.

Mockbusters are frequently masterpieces of surrealism. Their only desire is to be safe and generic, but they always feel uncomfortable, creepy, freakish, and strange. You might say they follow the rules so hard they break them.

2002’s Max Magician and the Legend of the Rings is an archetypal mockbuster. It wears its can’t-fail concept on its sleeve (or cover): Lord of the Rings was making money, Harry Potter was making money, so if you combined those things into one movie, then hell, you’d make money squared. Money times money. Hopefully this plan worked, because the director clearly had crack debt times crack debt.

What he didn’t have was a budget, actors, set designers, producers, or writers. Nobody involved in the movie seems to know what they’re doing, and some actually appear to be held on set at gunpoint. The result is an experience that has to be seen to be believed: a disastrous collage of fantasy cliches whose shamelessness is matched only by their incompetence. You feel genuine embarrassment for everyone in the zoning district.

Story? A young amateur magician called Max Majeck (you just heard the movie’s funniest joke, by the way) finds a doorway to a fantasy world under attack by a guy in a Ren Faire costume. Max saves the day by reading incantations out of a magic book, unleashing awesome spells such as “slowly levitate a few sticks of wood” and “cause several mice to appear on the villain’s shirt”. Watch out, Stephen Strange.

Everything about the movie is misjudged, including the decision to make it at all. The “fantasy realm” is clearly the woods outside someone’s house. The movie introduces an old, wise mentor character, forgets about him, introduces a second old, wise mentor, and then forgets about him. There’s a character called “Mr Tim” who refers to his wife as “Mrs Tim”, probably because it was too much work to come up with a woman’s name.

Like any truly bad movie, it’s actually hard to critique: it’s a firehose of awfulness overwhelming any cogent attempt to analyse it. An example of the rollercoaster ride the film takes you on: there are elves. They have pig ears. The pig ears don’t match their skin tone. The queen of the elves is played by the same actress who plays Max’s mom. She speaks with the same Midwestern accent in both roles. I literally can’t focus on any one thing because there’s always something worse distracting me.

But the audio stands out as exceptionally horrible. The music is completely inappropriate, sounds like it came from a free stock library, and was queued into the film by a deaf person. Countless lines of dialog are dubbed, suggesting that their original audio was spoiled somehow. They must have rewritten the dialog too, because the lips generally don’t match the voices.

I have to correct some misunderstandings the internet has about Max Magician. The first is the claim (featured on IMDB) that “There are no rings.” No, there are rings in this movie. Mr Tim’s book references magic rings. Dagda steals a green ring from Queen Belphobe.

The second misunderstanding is that it’s just a ripoff of Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter. That undersells the film’s ambition: it also rips off The Chronicles of Narnia (the talking mouse character + the children travelling between world plot point), The Neverending Story (the enchanted book), and Jim Henson’s Labyrinth (the goblins-bickering-in-the-closet scene at the end.)

It’s fairly good “make fun of bad movies” fodder. I suggest going into Max Magician armed with a few facts about it’s production, such as the fact that the weapons are literally pool noodles, or that the talking mouse Crimbil is portrayed by two different mice after the first got eaten by a snake. (You can notice this on-screen because the two mice don’t quite match in color: OG Crimbil is slightly gray, while Emergency Backup Crimbil is slightly brown. Can you identify which scene contains which Crimbil? This could be a drinking game. )

Mockbusters are designed to be disposable. Strangely, this one picked up a second life after pop culture commentary Youtube channel Red Letter Media tried (and failed) to review it. Their video was corrupt and displayed 86 minutes of static. I think my video’s corrupt, too. It displays 86 minutes of shitty movie.

(Ironically, “mockbuster” is itself a linguistic mockbuster, riding on the fame of two prior words – mockery, and blockbuster – to achieve its affect.)

This featurette opens Monty Python’s 1983 film The Meaning of Life, and is my favourite part of the film. Hail Terry Gilliam.

It’s a parody of a pirate movie, filled with swordfights and swashbuckling and people yelling “‘ard to starboard!”. But as with Brazil, it’s actually a kind of fear teabag, steeped in subtle flavors of alarm, disquiet, and anxiety, releasing those flavours upon repeat viewing. You can’t separate The Crimson Permanent Assurance from the year 1983, or from Britain.

Incredibly, people once trusted banks. Almost. The local bank was like the local butcher: probably holding a finger on the scale, but at least you thought you understood him. He was part of your community. He was yours.

In the 80s, that started to change: the globe shrank, trade deals and computerized systems enabled companies to spread their tentacles across continents and oceans, and suddenly your bank was no longer part of your community. It was a shadowy, alien thing from somewhere else. Maybe the outer dark.

Finance has always had aquatic metaphors. Cash flow. Liquid assets. Trickle down. Mutual pools. Skimmed profits. As the financial sector exploded in size and complexity, the metaphors became more pointed. Loan sharks. Corporate raiders. Headhunters. Buccaneers. The idea that finance firms had become something akin to pirates is a compelling one. Amoral entities afloat a sea of cash, with no masters, no Gods, no loyalty but to the firm, flying the flag of civilized commerce only when it suited them. Scuppering enemies with leveraged takeovers. Burying treasure in offshore tax havens. Terry Gilliam’s idea was to make the finance = piracy metaphor literal.

The featurette opens with a bunch of elderly accountants slaving at their desks, while young men with American accents boss them around. (This reflects another British anxiety from the period: that venerable and supposedly honest British institutions would be swallowed by faceless American corporations). When one man gets fired, the rest mutiny, throwing their American overseers “overboard”. They then turn to a life of crime, sailing their building through London as if it were a ship, plundering and pillaging.

It’s a great bit of absurdist comedy, and Gilliam has fun turning accountants into pirates. They wield “cutlasses” made from the blades of office fans, fire “cannons” that are actually spring-loaded desk drawers, etc. There’s little Pythonesque wordplay, and almost every joke is a visual one. It’s almost like watching a comedy sketch made for deaf people; although they’d miss out on the bombastic score.

There’s the usual artsy film touches. The Crimson Permanent Assurance building is almost comically antiquated, even older than the men inside it, but the buildings they plunder are sleek and modern, webs of glass and steel spun by giant spiders (emphasising a theme of old vs new). The opening shot of downtrodden accountants hunched over rows of desks is matched with a parallel shot of the same men pulling oars in a Roman slave galley. The amount of money spent on tiny details must have been staggering. That list of subsidiaries on the corporate boardroom of the Very Big Corporation Of America? There’s actual stuff written there.

The film ends with the narrator cheerfully describing how The Crimson Permanent Assurance took on the world with their business acumen…and we see bleak shots of the building sailing across a desolate skyline, having destroyed everything. Then it falls off the edge of the world, and the rest of the movie begins.

The Pythons each brought something special to their troupe. Cleese and Jones had their characters, Idle had his music, Palin had his writing, Chapman had his dramatic acting skills. But the visions? The dreams? Those, in large part, came care of Mr Gilliam, and here’s proof, sailing across the main.