“Jack and the Beanstalk” is the American Psycho of fairy tales.

The hero breaks into a man’s house, steals his possessions, and murders him when caught in the deed. Most retellings add a clumsy exculpatory backstory (the giant killed Jack’s father, or something), but the tale has enough malevolence to be an interesting choice for one of the Disney studio’s “fairytale + mouse” adaptions.

Mickey and the Beanstalk was released with center billing in 1947’s Fun and Fancy Free, and re-cut for TV several times with different narrators, including Ludwig Von Drake, Shari Lewis, and Winnie the Pooh voice actor Sterling Holloway. The tale begins in Happy Valley, where “all the world is gay”. The gayness stems from a magical harp, which is stolen one fateful night. The crops fail and the river dries up, leaving three unfortunate peasants (Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Goofy) facing starvation. There’s a hilarious gag involving Mickey Mouse slicing transparently thin sandwiches from a single slice of bread.

Mickey foolishly trades their last cow for some magic beans, which grow into a huge beanstalk, reaching up into the clouds and a giant’s castle. The giant is one hell of a dude: you’d think merely being a giant would be enough, but he also possesses magical powers allowing him to fly or transform into anything. It’s like the Tommy Lee/Pam Anderson sex tape, where we discover that, in addition to being a millionaire rockstar, Tommy Lee also has a huge penis. Some guys get all the luck.

Mickey’s plan to trick the giant into turning into a fly and swatting him fails, and Donald and Goofy are locked inside a snuff box. This leads to the film’s most nail-biting moment – Mickey stealing the key from the giant’s pocket while he sleeps. It’s unfortunately necessary to kill the giant at this point, which they achieve through a method that doesn’t make a lot of sense given what we know about his powers.

Mickey and the Beanstalk is well animated, well conceived, and has some laughs. If I had a complaint, it doesn’t find a use for Goofy. Disney’s “big three” are types: Mickey is the straight man, Donald is angry, spiteful, and insecure, and Goofy is the good-natured fool. The latter role is filled by the giant, giving Goofy nothing to do (except a cute scene where he tries to rescue his hat from a giant-sized block of jelly).

There is (perhaps) a deeper level to this film than I initially thought.

In 1913, an aqueduct was built, diverting the Owens River to Los Angeles. This enabled La-La Land to grow to its current size, but it had a dark side: Owens Lake completely dried up, devastating Owens Valley and ruining the livelihood of many farmers. The man responsible for this was William Mulholland. It might be a coincidence, but the name of the giant is “Big Willie”. I also note that Owens Lake is only a three hour drive from Burbank.

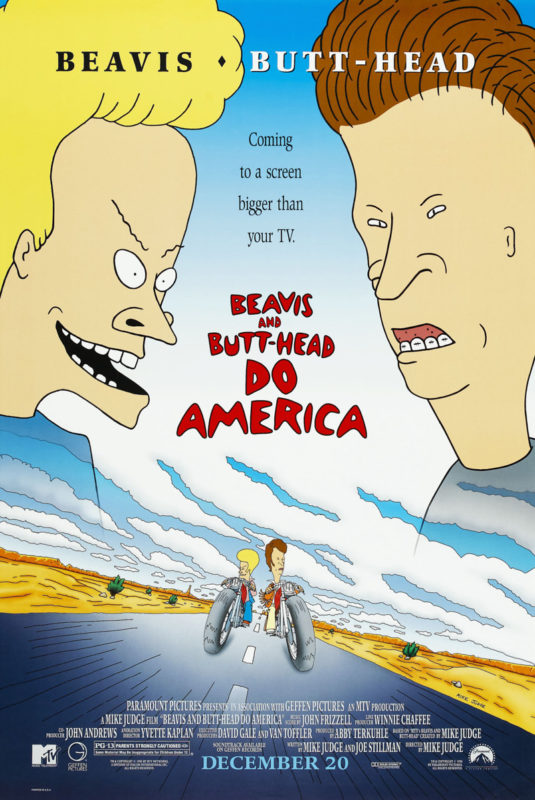

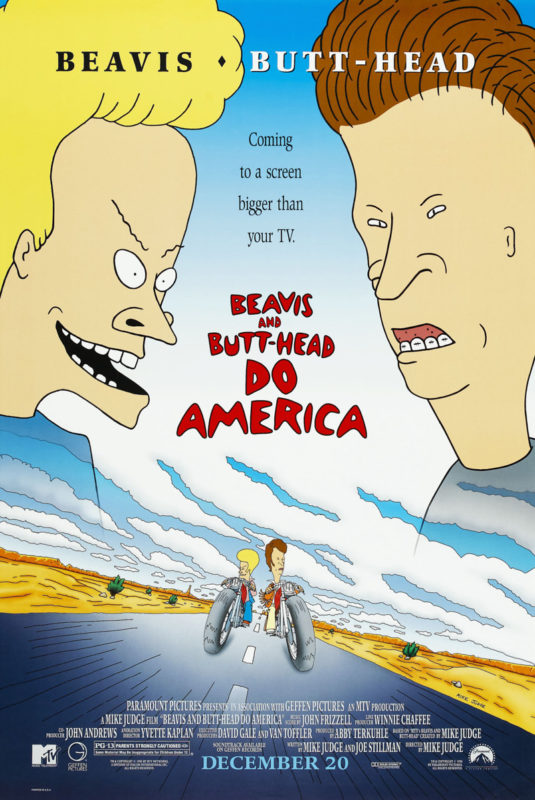

Beavis and Butthead wander around America, being so stupid that they’re almost immortal. The show itself works the same way. It’s one-dimensional to the point of being immune to criticism: everything is right there, on the surface, an inch from your face. There’s nothing to “unpack”. There’s no message, or subtext. Merely by reading the title, you’ve plumbed its deepest depths.

Read contemporary reviews and you’ll see flop-sweating critics trying to find nuance in a show that doesn’t appear to have any. What can you say about Beavis and Butthead? That it’s a show about two idiots? Is that it? Is there anything deeper going on at all?

Maybe. Let me attempt an explanation:

The show is an extreme parody of Generation X nihilism. The 80s became the 90s, the Berlin Wall fell, Nirvana’s Nevermind came out, and millions of young people collectively decided it was uncool to care. Your clothes? Flannel and torn jeans. Your career? Skateboarding, or playing guitar in a local band called Turdsplatt. Your death? Late twenties, overdosing on some fashionable drug (probably heroin.)

Generational contempt hit an all-time high. Parents in the 60s thought their kids were commies, parents in the 80s believed their kids were devil-worshippers, but at least those things require initiative. Now, kids just sat in front of the TV all day, growing dumber and less curious by the second, as the Ozone layer burned and bombs pounded Vukovar. For the first time, the youth weren’t scary, just embarrassing.

Yes, this stereotype was unfair. The most famous Gen X’er, Kurt Cobain, was industrious, introspective, and mentally ill, not an apathetic slacker. But the lack of fairness is sort of the point: Beavis and Butthead are caricatures from baby boomer imaginations, rendered in full ridiculousness. Mike Judge isn’t mocking teenagers, he’s mocking their parents. “Look at this. Is this really what you believe your kids are like?”

But what about the movie?

The story begins with Beavis and Butthead noticing that their TV has been stolen. After pronouncing weighty judgement on the situation (“this blows”), they set out on a journey to find a new one, road-tripping across America and snickering at every sign on the interstate (“heh heh…Weippe…”)

They’re soon wrapped up in a drama involving government agents, a deadly bioweapon, and the President. The specific details are unimportant, since Beavis and Butthead successfully misunderstand or ignore every single thing that happens to them (no mean feat, as one of them is an elbow-deep cavity search). There’s funny jokes, and even some pretty good animation (particularly a peyote-tripping scene created by Rob Zombie).

Roger Ebert enjoyed the film, but noted his difficulty in telling the two central characters apart. I can confirm that they are distinct: Butthead is taller, has dark hair, and is somewhat more intelligent. He wears an AC/DC shirt, which I always thought was a little off (Metallica is fine, but AC/DC was a band your dad listened to). Beavis is an anarchic force of chaos, barely held in check by an occasional “shut up, buttmunch” from his domineering friend.

B&BDA is 25 years old, and many of its cultural references seem dated. In another 25, it will need a Rosetta stone to be understood. It came out in 1996, and although it made money there wasn’t a sequel. The show was cancelled in 1997, and for years it existed in a weird dead zone: too old to be relevant, but not old enough for a nostalgia-fueled comeback. That happened in 2011, although the show will probably never command the level of attention it had before.

B&B don’t really work when you transplant them into modern times. In 2018, it’s old people who sit around watching TV all day, not kids.

But some parts of Beavis and Butthead haven’t aged, and some that did really shouldn’t have. When government agents try to track the duo down, they use a fax machine. Beavis and Butthead are stupid, but there are worse things. There is intelligence paired with malice. They should be glad that they weren’t living in 2018, smartphone addicted rather than TV addicted, with the NSA understanding them far better than they understand themselves.

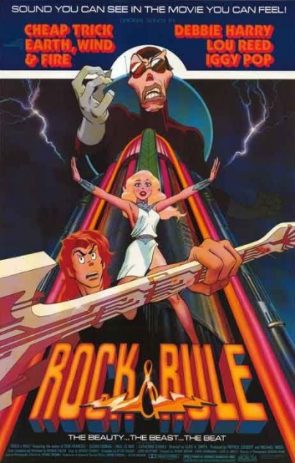

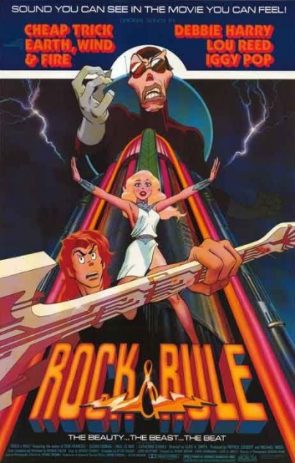

This is a 1983 Canadian post-apocalyptic science fiction fantasy musical adult* cyberpunk neo-noir animated furry i hope i die

The plot is incidental (and embarrassing); cartoon mice save the world through the power of rock. It’s based on a 1978 Nelvana TV special called The Devil and Daniel Mouse, but updated to be edgy and dark and very, very serious. The songs are pretty thin, and guitars are wielded more often as weapons than as instruments.

But there are good moments, too. Some nice animation, and occasionally great character design. I say “occasionally” because it partakes in animation’s most onerous trend: Humans with Dog Noses. Who started the HWDN craze? Carl Banks? The Beagle Boys were obviously cartoony, but here we have straight-up humans with dog noses. It looks ridiculous, and immediately deep-sixes the edgy, dark, serious premise.

Dog noses are the first of many questionable artistic choices. The supporting characters are drawn like funny animals, but the lead characters are drawn realistically. They don’t seem to exist in the same world, and when whenever a lead and a support stands together the sharp disjunct between the two styles is all you can focus on.

My favorite part of the movie is everyone’s favorite part: the villain Mok. He steals the show with one of the most innovative character designs I’ve ever seen in an animated movie: a pastiche of Mick Jagger, Lou Reed, and Thin White Duke-era David Bowie. His face is an unimaginably complex manifold of vertices and angles, blending the feminine and masculine (and canine, but I’ve made my point), and the animators deserve kudos for keeping his ridiculousness on model. The movie suffers greatly whenever Mok’s not on screen, although there are fun computer-generated visuals and Debbie Harry does the best job she can.

The story in brief and in full: Mok (“the only Ohmtown rocker to go gold, platinum, and plutonium in one day!”) is seeing his commercial success wane, and hatches a plan to summon a demon from hell so he can…I dunno. I seriously have no idea what he’s trying to do, but we never understood what David Bowie was trying to do in real life, so there you go.

He kidnaps the female singer from a shitty glam rock band, because only her voice can complete the satanic ritual. Her dislikeable male co-singer has to rescue her along with some bumbling comic relief characters, who are more like comic constipation. Mostly, the movie succeeds in making you groan and cringe, such as when we find out they’re playing at Carnage Hall in Nuke York.

Bootlegs credit the film to Ralph Bakshi, which is false, yet also true, because this sort of movie probably wouldn’t exist without him. The success of Wizards and Fritz the Cat ushered in a few brief years when studios gave a bit of rope to animated films that weren’t obviously for children.

The rope had apparently played out by 1983, and Rock & Rule feels tampered with. The Gibsonian cyberpunk atmosphere is leavened with moments of wacky slapstick that could have been spliced in from Goof Troop (they couldn’t, for chronological reasons, but the vibe is similar). In particular, Mok’s henchmen ride around on rollerskates, which might have been an effort to save money on animation. When your characters are on wheels, it doesn’t matter if they slide around on the frame.

If a studio meddled with Rock & Rule, this is understandable. The film is confused and hard to market, and I’m still not sure who it was for. But it didn’t make any money even with all the commercial compromises, so why did they even try? Go for broke on your crazy post apocalyptic rock musical furry whatever! I’m reminded of this exchange from Karate Kid:

“I’d get killed if I go down there!”

“Get killed anyway.”

* (“Adult” means two fully-clothed characters feeling each other up, implied drug use, a Satanic pentagram, some intense imagery, and one character calling another “dick nose”, which if true would still be an improvement over dog noses.)