So obscure it hardly exists: The Buddha of Suburbia is a quasi-soundtrack to the BBC serial of the same name, based on a book of the same name, written by an author of not the same name (he’s called Hanif Kureishi – “Mr Buddha of Suburbia, Esquire” would be a bad name, although perhaps not as bad as “Zowie”.)

On my first listen, I hated the first song so much that I didn’t listen to the rest for a long time. This was a mistake: “The Buddha of Suburbia” might be adult contemporary glurge, but everything after it is fascinating, and much of it is good.

It’s Bowie’s scrapbook circa 1993, filled with doodles. It’s his most disjointed studio album if you consider it one, the hyped-up penny arcade chiptune of “Dead Against It” is followed by the adventurous world music of “Untitled, No. 1”, which is followed by about six minutes of gentle fuzz and crackling sounds. Some tracks are reworks of the TV show’s music, while others are new. A proper soundtrack to The Buddha of Suburbia still hasn’t surfaced, and likely never will.

The book, from what I remember, was about being a mixed-race Britain, separated from both white and Indian. The songs all exist alone, and can’t be discussed in relation to each other.

“Sex and the Church” is a house track that prefigures Black Tie White Noise. It makes its point – my main problem is that it’s incredibly overlong, and only has about two ideas.

“The Mysteries” is Bowie’s first ambient track since 1981. It sounds similar to Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports, which was created to be both “interesting and ignorable”. An organ builds ominously, like a cloud that never causes rain. Again, it’s very long, but it’s an intriguing experiment.

“Ian Fish, UK Heir” is an anagram of “Hanif Kureishi”, and it’s an even stranger ambient piece that evokes peaceful unlistenability. Sometimes hints of melodies appear in the suffocating carpet of fuzz.

“Untitled, No. 1” is loaded with exotic instrumentation, and Bowie sings in another made-up language. Why no title? Scott Walker released an album in 1984 called Climate of Hunter where most of the songs had no names, they were just “Track Three” and such. This was intentional, he felt that titles would overbalance the songs like poorly-weighted boats – the listener would focus overmuch on the title instead of the lyrics. There might be a similar logic here, as “Untitled” certainly seems too broad-reaching to be pinned down the way “Warszawa” et al can. Chris O’Leary thinks it’s supposed sound like a painting, which is another credible interpretation.

The standout is “Strangers When We Meet”, although you’d never know if you only heard the Buddha version, where the fluffy production robs it of its power. It appears in a much stronger form on 1. Outside, and I still consider it a track from that album.

The final song is “The Buddha of Suburbia” again with Lenny Kravitz on guitar or something. It continues to suck.

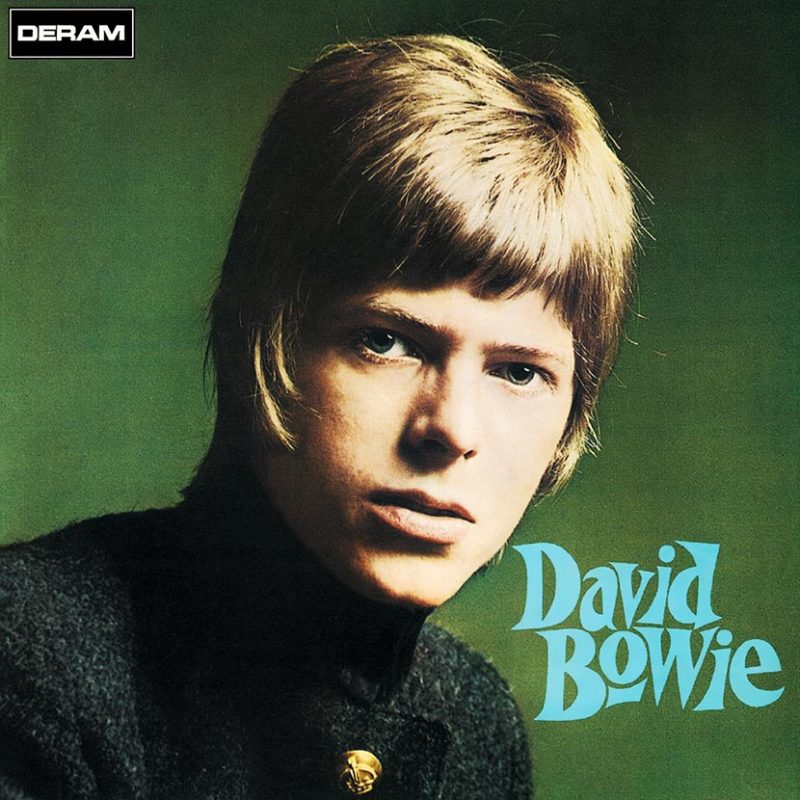

In 1967, David Bowie’s recording career began…and didn’t.

Well, it depends. What do you consider a beginning? Metallica’s first album is Kill ‘Em All, but that’s just a Diamond Head imitation. Their signature sound emerged on Ride the Lightning. That’s their beginning. The first Mad Max movie came out in 1979, but it’s just a violent exploitation film: the series truly starts with Mad Max 2. Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series begins with hallucinatory fragment The Gunslinger: but the story only truly takes shape with book 2, the Drawing of the Three.

First efforts are usually flawed efforts, contaminated by inexperience, self-doubt, and outside interference. They’re not “real” starts, any more than Michelangelo’s first cast-off lump of clay was his first sculpture. David Bowie probably existed by 1969, and certainly by 1970. But in 1967, the cards were still falling. Whoever this is, it isn’t him. Not yet.

David Bowie is musically bizarre in light of his later albums: fourteen show-tunes for shows that never existed. It never misses a chance to be quirky, chirpy, and naff, the songs are bedecked with organ and keyboard parts, and Bowie (who had just turned twenty) does a fine job of sounding like an elderly sex pest.

It draws aesthetics from music hall, a venerable tradition that was fading in the 1960s, and is now utterly unendurable to modern listeners. I have never met a person who likes music hall. Have you? Do they exist? I’ve met people who claim they’ve seen aliens, but the elusive music hall fan still avoids me.

Music hall featured (and relied upon) stage shows and live performances: it may have been the the 19th century’s equivalent to the music video. The album suffers for its lack of a visual element, and feels a bit flat. No doubt Bowie had planned out short films and mime performances and dancing bears for each one, but then the album flopped. The songs are like colorful little parrots, their plumage covered by a dropcloth. We can hear them well enough, but they’re less charming without their bright feathers.

The music is mostly in good order. Even at twenty, Bowie knew how to put a song together. “Love You ‘Till Tuesday” strides into its chorus with a ritardando that made me say “nice” out loud in the middle of an empty room, which was embarrassing. “Sell Me A Coat” is a catchy ohrwurm, hand-tailored for the single release it never received.

The lyrics are a high point, although they’re definitely more interesting than good. Music hall was “low” entertainment, attracting people gate-checked out of polite society, and it played music to match. Bowie takes full advantage of this and just lets it all hang out, writing anything that will scan, no matter how stupid or awful or anti-social.

“We Are Hungry Men” is a humorous science fiction dystopia about a dictator’s solution to overpopulation. I laughed at the line about people being allotted a cubic foot of air to breath, although the part about China someday having “a thousand million” people didn’t age well.

“She’s Got Medals” is Bowie’s first song to deal with transvestism (“Passed the medical! Don’t ask me how it’s done!”), and “Little Bombardier” takes a nasty turn into pedophilia. The closing track is a spoken-word piece called “Please, Mr Gravedigger”, which tightrope-walks between being ludicrous and genuinely horrific.

There’s a lot of filler and half-songs (and quarter-songs), and I won’t pretend I want to hear things like “Come and Buy My Toys” ever again, but the songs are so diverse it hardly matters. They’re presents under a tree: if you don’t like one, you try your luck with another.

Bowie did the same thing – you can see many possible futures for him, refracted in the facets this strange, strange album. A mime? An actor? A vaudeville hoofer? A hippy? The genius who wrote Hunky Dory? I’m glad he chose the future he did, because it easily could have gone another way. In June 1967, an album came out that would change the face of pop forever. This, however, is not a review of The Beatles Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, but the first David Bowie album.

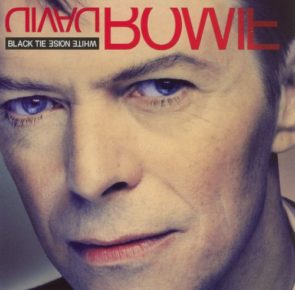

Black Tie, White Noise is legendary, and not just for having a punchable album cover. When it came out in 1993, it marked Bowie’s return from the wilderness – his first solo album in six years. Just try holding your breath for six years – I bet you can’t do it. You probably won’t even make it halfway.

Bowie spared no effort in trying to tank it. He re-united with Let’s Dance producer Nile Rogers, who recounts baffling self-sabotage inside the studio. A potential smash hit (the Madonna-ripping “Lucy Can’t Dance”) was demoted to a mere bonus track. The final tracklist seems to emphasize the artistic and non-commercial songs, particularly a piece composed for David’s wedding to Somali fashion model Iman.

BTWN is a cold, funky dance record. They pulled 70s disco out of cryogenic suspension, partly thawed it, and added some 90s production elements. The album contains the snappy, bright Cheiron Studios sound that was all over the charts at the time, along with sampled beats and grafts from jazz and swing. At first the album’s sonics impress (as Let’s Dance‘s did), but soon you want to hear distorted guitars, and roughness, and humanity. BTWN is too clean. Actually, it’s germophobic.

A couple of the songs connect with me. “They Say Jump” delves into societal pressure through the metaphor of Bowie’s half-brother Terry, who had committed suicide some years before. It’s the closing parenthesis to “The Bewlay Brothers”. “Nite Flights” is a cover of a Scott Walker song, adding lots of air to what was already a large and generous-sounding arrangement. And “Pallas Athena” is a furious and crushing dance track, woven out of thudding drums and stentorian vocal samples.

The title track is a self-conscious aping of “Fame” from Young Americans. Carlos Alomar’s riff is replaced by a funky slap-bass part, the descending “fame”s at the end replaced by ascending “yow-yow-yows” at the beginning, John Lennon replaced by someone called Al B Sure! (whose career spiraled the drain after doing this collaboration). The half-rapped ostinato (“Black! Tie! White! Noise!”) is quite good, although I could do without the “crankin’ out the white noy-oy-oise” chorus.

The lyrics are McCartney’s “Ebony and Ivory”: a guilty white guy talking about how mankind is a beautiful rainbow, with a black musician dutifully playing Br’er Rastus in his minstrel show. I always dislike these types of songs, mostly they’re never as brave as they think they are. “I’m a face, not just a race!” Bold words in 1993. The lyrics reference the Rodney King riots, but still end with all the usual cliches of black and white man holding hands and becoming one. You know what I’d like to hear? A song that’s about how different we are. That maybe black and white aren’t the same, and we need to come to terms with that in whatever way we can. It would be career suicide, but at least it would be a fresh take on things.

The rest of the album is unmemorable. What artistry it has overwhelmed by a driving sleet of digital breakbeats and pad synths. Bowie’s vocal melodies are slender things, unable to support the weight of the arrangements. To be blunt, I don’t need to listen to Bowie for 56 minutes straight, nor do I need to hear about his wedding. The tacky “modern” elements just emphasise how little of the old Bowie is present on the album.

Comparisons can be drawn to another album, twenty years earlier, when Bowie was also newly married. But where The Man Who Sold the World became a classic, Black Tie, White Noise is sadly the first of many inconsistent and often uninteresting 90s efforts.