“Transition…” – David Bowie, “TVC15”, Station to Station

He was right to muse on it, because transition is interesting. Not medical transition (though that must have intrigued him also), but philosophical transition. Ship of Theseus. Lumpers vs splitters. Much of philosophy is based around the question “when does a thing become something else?”

Is transition a continuum, like day becoming night? Or can it be quantified into discrete steps? Historians have spent countless hours wargaming World War II, trying to isolate the point where Hitler definitely lost. Was it 1940, when the Luftwaffe was crushed in the Battle of Britain? 1941, when the United States entered the war on the Allied side? 1942, when Stalingrad held? When was the final moment that Germany could have won World War II, and after which, they absolutely couldn’t? And how thinly can we slice the bratwurst? A month? A day? A single second?

Aladdin Sane is an exposition of transition. We see Bowie at a cracking point, where fame was becoming overwhelming, a burden. He invented a new character, a guy with worms filling his brain and white-ants eating his bones, but his confusion was no fiction. Over the next year his backing band would either leave or get fired, unable to handle his egomania and drug abuse. The paranoid Berlin years have their genesis here.

Musically, it’s fierce and punishing: along with The Man Who Sold the World, this is the heaviest thing Bowie ever recorded. But it has an experimental side that, again, seems like a preview trailer for Berlin. Transitions. Beginnings and ends.

We see both sides of the album, right out of the gate. “Watch That Man” is a loud party song – Bowie (perhaps in character, probably not) is at a party, noticing scenes of glitz and glamour and pronouncing them merely “so-so”. Maybe it’s not even that. Maybe it’s about to become a nightmare.

“Aladdin Sane (1913-1938-197?)” is the end stage of that party. The song is dominated by a 45-bar avant-garde jazz solo by pianist Mike Garson. Surely Bowie’s brilliance was becoming impossible to deny by now. Damned well nobody else was doing stuff like this in 1973. What’s the meaning of the dates in the titles? 1913 was the year before World War I. 1938 was the year before World War II. Does this mean that Bowie thought that the third World War would happen in the 70s? And did it?

“Cracked Actor”, “Jean Genie,” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together” are homages to or parodies of the Rolling Stones. The guitars crush and maul, and his vocals sound both inspired and exhausted. “Time” sees a new influence popping up: Jacques Brel, who he discovered via Scott Walker. “The Prettiest Star” is a lovely song: it was originally his failed second single, here remade with Ronson’s guitars and some added backup vocals.

The album overflows with great music, but two songs overshadow the others.

The first is “Panic in Detroit”, anarchic and violent, a track which burns with the guttering energy of a trash fire. The female backing vocals pull its genre way from rock, making it sound as indeterminate as any riot. The second is “Lady Grinning Soul”, a delusive opium dream made music. I like it every bit as much as “The Bewlay Brothers”, which means Bowie scarcely ever wrote a better song.

Aladdin Sane is far tighter (and a good bit better) than Ziggy Stardust. The Mick Jagger meets Jiminy Cricket character of Ziggy Stardust evolved into Aladdin Sane, a manic guy caught between two transition points and being torn apart by fame. The trip is finishing, and the come-down has begun. This is 3am insomnia, the album: paranoid, anxious, and still unable to sleep.

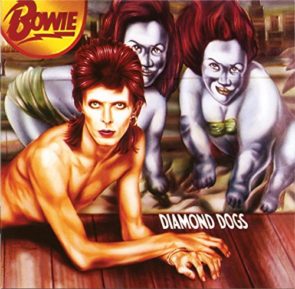

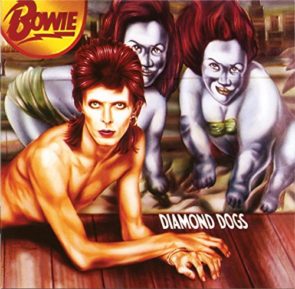

David had a remarkable talent for throwing fragments down at random and having them form a complete picture. Diamond Dogs is a fractured album with mismatching halves (the first a concept about a post-apocalyptic gang that rides around on rollerskates, the second an abortive attempt at a stage musical version of Orwell’s 1984) but it ends up being one of his most complete-sounding records.

The halves feed each other, and bleed onto each other. The post-apocalyptic tracks form an optimistic beachhead, which the 1984 side effectively quashes. First the fire, then the flood. I’m reminded of Harlan Ellison’s A Boy and His Dog: gaudy adventures in the wreck of the Earth, with a grim final page.

The title track is probably the worst song: it sets the tone, but doesn’t get out of the way when it should. Why is it six minutes long? It’s the most blatant homage to the Rolling Stones Bowie ever wrote, and one of the last. Sometimes I skip it.

“Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing Reprise” is a genius-touched epic, farmed from William S Burrough’s technique of cutting up lines and reassembling them (again with the happy accidents). Bowie’s singing is wonderful, and the mood established by the scrambled lyrics are delirious scissored photographs of urban decay. The three tracks are curiously interchangeable, they all seem to work fine on their own, or in any order. Maybe their positioning is itself a cut-up.

Then “Rebel Rebel” opens with its scorching signature guitar riff, played by Bowie himself. This was his first studio release without Mick Ronson, and he seemed eager to upstage his former axeman. There’s interesting production elements going on in “Rebel Rebel”. Rock guitarists typically lay down two guitar tracks side by side (one panned left, the other right.) Bowie, it appears, only recorded one, panned dead center. This gives his tone a sharper, more brittle sound (compare “Rebel Rebel” with “Watch that Man” or “Hang Onto Yourself”), it cuts rather than bludgeons. It’s a great riff, however it was recorded. There’s a legendary story about how tennis legend John McEnroe (fresh off of Wimbledon), attempted to play it in his hotel suite, and botched it so badly that Bowie himself overheard from the room below, and banged on the door to correct him.

As with “Diamond Dogs”, “Rebel Rebel” feels gaseous. There’s a perfect ending point at 3:30 that Bowie blows right past, continuing for another minute. Rock DJs soon got into the habit of dropping the axe at three and a half minutes, and soon Bowie was doing the same (as you can hear yourself from the version on Reality, for example). Some of David’s songs (eg “Breaking Glass”) grew longer with time: this one grew shorter.

Then the 1984 half of the album begins, which is the stronger side. The songs work marvelously, whether alone or together, and there’s no pacing issues evident.

“Rock ‘n Roll With Me” is the last dance before the war begins. “We are the Dead” is a descending vamp through parlous gray madness, with none of “Rebel Rebel’s” optimism. The tinkling organ sounds aggressively and effectively fake – the sort of musical instrument they’d have in Oceania.

“1984” is a fascinating funk rock experiment, quite similar to the music on Young Americans. Then the album’s greatest track arrives, the astonishing “Big Brother”. “Chant Of The Ever Circling Skeletal Family” ends the album in primitive violence. The sudden, jarring end (in the middle of “Brother”) is particularly effective.

There’s still another story to Diamond Dogs which has nothing to do with apocalypses or Orwell: David succesfully staying in the game as an artist. At the time, the glam genre he’d hung his hat on was falling to pieces. For the first time, T-Rex’s new album was not a top 10 hit, and they never had another one. Mott the Hoople had failed to follow up “All the Young Dudes”. Was Bowie next? Would he join the rest of the glam rockers in obscurity, paved over by uncaring history?

Happily, Diamond Dogs was the album that achieved escape velocity, breaking free from Planet Glam. He left his old style behind, revealing that it had needed him more than he neededit. This is more than an album. It’s the sound of David fighting for his life and winning.

“Great” is a landmine in the English lexicon. It means “eminent or important”, but has picked up a secondary meaning of “qualitatively favorable”. Hitler was a great man, and Hitler wasn’t a great man. Both of these statements are true; sometimes important things are not good and vice versa.

Let’s Dance is great. The album broke Bowie in the United States, and it’s clearly one of the most important things he ever did. Soon Bowie would be on the run from its shadow, trying to recreate it and failing (Tonight), then unsuccessfully circling back to what he had before (Tin Machine). But time has diminished Let’s Dance, and made its weaknesses more apparent. You might say it’s dancing on feet of clay.

The songwriting is very smart (absolutely to a fault). The title track opens with harmonised vocals stepping upwards in thirds, a postmodern reference to the Beatles’ “Twist and Shout”. “China Girl” contains a pentatonic major melody that suggests the famous Oriental Riff. Everything’s allusions and callbacks, Bowie trying to fill dance-floors while remaining palatable to theater types.

The production glitters like diamonds. Cubic zirconium, maybe, but for a few minutes you’re having too much fun to notice. Nile Rodgers’ mix is all edge and cut, meant to decapitate dancers through a club PA. A careful listen reveals that the mid-range frequencies are scooped away, turning the album into a flashy but hollow facade. It’s all highs and lows, and lacks substance. There’s little guitar (why pay Stevie Ray Vaughan for his time and then not use him?), and when it appears it sounds thin and weak.

Side A contains all the hits, plus the forgettable “Without You”. Side B is the more uncertain and interesting one. “Richochet” puts its snare on the 1 and 3, giving it a staggered rhythm that sounds “off” even though it’s perfectly on. The lyrics are portentous enough for the drums to sound like bomb blasts, with Bowie’s vocals a robotic call to take shelter. Not a great track, but you finally see some struggle from Bowie, which is a relief on an album as mercilessly polished as an Apple tech demo.

“Cat People” is a remake, “Criminal World” a cover, but both come off fairly well in Nile Rodgers’ hands (although “Cat People” loses its mystery and rushes to the climax too early). “Shake It” is a disposable dance song that pads out the minutes, and then the album’s over. It’s shocking how fast the Let’s Dance ends, and how little music you’ve heard.

There was nowhere to go after Let’s Dance. It annexes itself with sheer power, the way nuclear warfare ends the need to its existence. Let’s Dance is exterior and nothing else: an amazing exterior, nothing really has depth or stays with you. Low grows stronger every time I listen to it, and Let’s Dance grows weaker.

The album is like its production job – a big but empty musical souffle. It was a monster that Bowie never needed to fear: he was better than it, always. Let’s Dance is great album, but I cannot say that it’s a good one.