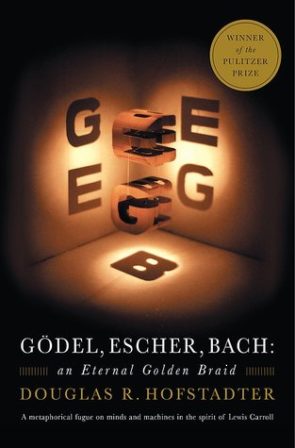

An 18th century German composer who wrote the theme for a king, with a principle melody that ascends yet remains trapped in tonal space. A 19th century Dutch artist who created maddening and hallucinatory artwork, defying intuition about perspective and reality. A 20th century German mathematician who described the limitations of a formal system addressing itself.

According to this book, Godel, Escher, and Bach were three blind men touching the same elephant: the Strange Loop.

“The “Strange Loop” phenomenon occurs whenever, by moving upwards (or downwards) through levels of some hierarchial system, we unexpectedly find ourselves right back where we started.”

You get on an elevator on floor 1, go up nine floors, emerge on floor 10, and then take the stairs back down. This is a loop. But imagine taking the elevator from floor 1 to floor 10, and the door slides open to reveal…floor 1. This is a strange loop.

“But things like that don’t exist.” They might not in architecture, but they do in the things that give rise to architecture: math, language, and human consciousness. Statements like “this sentence is a lie” and “I am nobody” are linguistic paradoxes. They’re like MC Escher’s Drawing Hands: destroying and recreating themselves over and over. Idioms like “pulling oneself up by one’s own bootstraps” are loopy. “This is not a pipe” is loopy. Barbershop poles are loopy.

One of the eye-opening parts of this book is how you start noticing strange loops all around you. The website you’re reading is powered by PHP, which stands for “PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor”. This isn’t a mistake: the language’s name is an acronym containing its own acronym inside it! Like spiders, strange loops exist closer to your body than you think.

But there’s more to strange loops than weird art and logic puzzles. Hofstadter seems to be poking towards a theory of consciousness itself.

In 1996, David Chalmers explicated the two main problems of consciousness. 1) How does a collection of atoms develop a consciousness (meaning a subjective experience, an internal monologue, or whatever). 2) Why does this happen? Why don’t we experience the world the way a robot might?

Hofstadter’s sense (never forcefully argued) is that strange loops are responsible for the consciousness we experience. Just as the three letters “PHP” contains an infinite number of “PHPs” inside them, our three-pound brains are able to “unfold” into something more than the sum of its parts, via iterations of very complicated loops. This doesn’t address the second of Chalmers’ questions, although in a later book Hofstadter compares the soul to a “swarm of colored butterflies fluttering in an orchard” – something attracted by the fruit, but not a part of the fruit. The loops don’t require conscious experience, the conscious experience emerges as a kind of froth when all of these loops combine.

This implies that an algorithm would be capable of introspecting about its own existence. A string of math on a very large blackboard would perceive the color red, and feel pain. It’s a provocative idea, but don’t expect to find this formulated with a QED at the end. As the constant artistic motifs suggest, GEB isn’t a hard science book. This is probably why people actually read it.

GEB is filled with illustrations, games, puzzles, and – most notoriously – dialogues inspired by Lewis Carroll. Some of these are astonishingly creative. The passage about the crab canon made me stop reading for a moment, because it was incredible, and I wanted to be able to remember it instead of immediately forgetting. It was mind expanding. Nearly mind-exploding.

Although GEB contains a primer on the basics of computer language, intellectual rigor isn’t the book’s goal. One of Hofstadter’s many interests is Zen Buddhism, which is our culture’s most potent form of anti-logic and as such is of interest to the student of the strange loop.

When the nun Chiyono studied Zen under Bukko of Engaku she was unable to attain the fruits of meditation for a long time. At last one moonlit night she was carrying water in an old pail bound with bamboo. The bamboo broke and the bottom fell out of the pail, and at that moment Chiyono was set free! In commemoration, she wrote a poem:

In this way and that I tried to save the old pail / Since the bamboo strip was weakening and about to break / Until at last the bottom fell out. / No more water in the pail! / No more moon in the water!

Zen never makes lessons easy for the student: you’re the one who has to do the work and become cosmic. But GEB makes the road far more fun than it has to be. What stands out about Hofstadter’s prose is how readable it is. Hofstadter isn’t a wordsmith, he’s a word alchemist, making dull things sparkle. The prelude to my edition contains a digression in the difficulties he had typesetting the book, which sounds as gripping as Hannibal crossing the Alps. (There’s also a somewhat cringeworthy part self-flagellating about the how the original printing of the book uses the default male voice.)

So is “loopiness” the way a collection of atoms can collectively seem to think, reason, and experience? The book leaves me unsure, as I think it was meant to. It’s the world’s longest Zen koan, fragments of information that never coalesce into a hard idea, but seem to get me closer to enlightenment than I was before.

Interesting aside: Godel, Escher, and Bach are three wise men (initials GEB), also the three wise men of the Nativity tale are Gaspar, Melchior, and Balthazar (initials GMB), also M is E rotated 90 degrees, also they brought gift of gold, frankencense, and myrrh (initials GFM), also F is the letter after E in the Roman alphabet, also “Godel” is nearly an anagram of “gold”, also I lied when I said this part was interesting.