Drop a stone in a pond. Ripples will spread out. Cultural events are similar, but sometimes the ripples occur before the stone falls. Facebook, iPhones, and The Lord of the Rings (books, not movies) are stones. Myspace, Blackberries, and The Hobbit (book, not movies) are ripples. Although important in their own right, they had the misfortune to occur before a similar (but much bigger) thing, and have been swallowed by it within the public mind.

Cassette tapes (and the culture surrounding them) were ripples: the stone would would fall twenty years later. They were ugly plastic rectangles containing about ninety meters of magnetic tape. Music recorded on them usually sounded hissy and noisy (this itself became an aesthetic), but the tapes were so cheap that it was now possible for the average child to copy music. People would tape songs off the radio (complete with hacky DJ voices and commercials), as well as make illegal bootlegs of live bands. This led to a full-blown kulturkampf between tapers and record labels in the 1980s, culminating in the BPI’s often-parodied “Home Taping Is Killing Music” slogan.

Some labels fought cassette tapes, but others embraced them. C81 (a compilation cassette released by NME at the start of the tape boom) is an example of the latter, containing twenty-four tracks of British and American “indie” music circa 1981. I’m sure that all the bands involved were branded as sellouts until their dying day.

The tracklisting is as schizophrenic and scattered as any fourteen year old’s mixtape: legends like Pere Ubu and Scritti Politti exist alongside bizarre “art” projects like Furious Pig that apparently did nothing notable except appear on C81. It’s both ethnically and musically diverse, with selections of funk, ska, reggae, dub and so on. Also, whoever put this together clearly wanted to fuck Lora Logic, because she’s on here twice.

As with many compilations, it sprays and it prays. “You won’t like everything, but you’ll probably like something.” I enjoyed the apocalyptic mini-epic “The Seven Thousand Names of Wah!”, the histrionic but understated “Shouting Out Loud”, the Scritti Politti song, and “Parallel Lines”, which is a thesis on everything punk should be: taught, fraught, and small.

But the best piece of music C81 has to offer is Cabaret Voltaire’s “Raising the Count”, which initiates the listener into a kind of electronic Satanic ritual: a black mass powered by 200 watts. The song is as destructively repetitive as a pneumatic drill rammed through your basilar membrane. You will either turn it off in confusion, or get sucked into a hypnogogic state. Cabaret Voltaire had existed for most of a decade by the time C81 came out, and would continue to release music for about twelve more years (although I find their later techno/house music to be less interesting than their early experimental work).

So, good music, and good capture of a particular moment in British musical history. C81 is now most easily acquired in digital form, which was the next evolutionary stage of tape culture. Cassette tapes were ripples, and digital piracy was the stone, doing everything cassettes had done (including killing the music business) about two orders of magnitude more successfully. The record industry profiting off tape trading seems gruesomely poetic in retrospect. It’s as though Louis XVI, before the French Revolution, had invested royal money in guillotines.

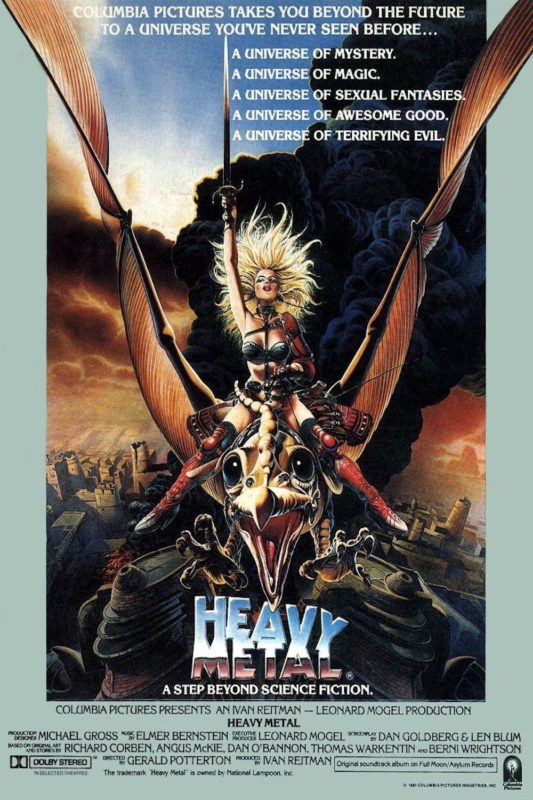

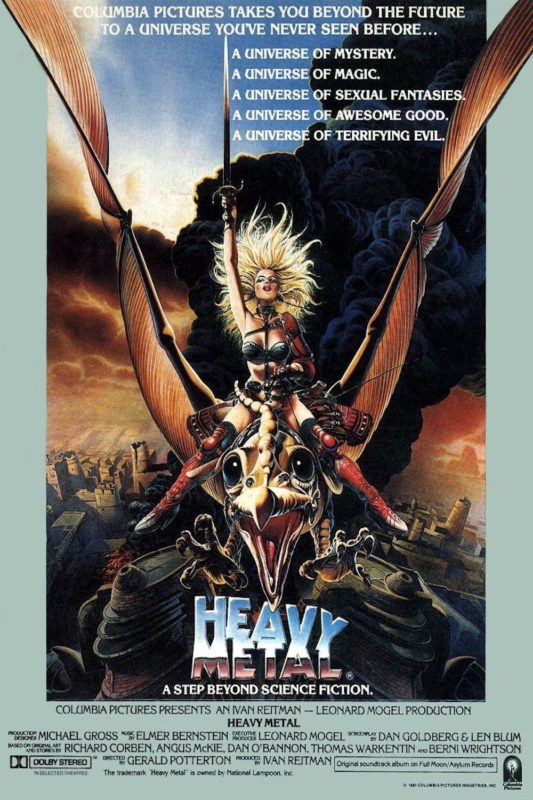

I decided to watch the 1981 animated film Heavy Metal because of its reputation.

Like Vegemite and the blonde German chanteuse on the first Velvet Underground album, Heavy Metal doesn’t have an especially good or a bad reputation; it merely has one. It grossed $20.1 million on a $9.3 million budget, enough to be considered a mild hit but not enough for a sequel. It has 6.7/10 on IMDB and a 60% Rotten Tomatoes score (critics’ consensus: “sexist, juvenile, and dated”).

It’s based upon the Heavy Metal comics anthology, which in turn is derived upon Métal Hurlant, the legendarily explicit French outfit home to everyone from Paolo Eleuteri Serpieri to Moebius; the film adapts stories from the comics, which vary from erotica to science fiction to horror. The art style changes from segment to segment, ranging from itchy “realistic” rotoscoped footage to stuff that could be a Saturday morning cartoon.

I watched it once. It made an impression. I watched it again. I decided I really liked it.

Halfway through my third rewatch, I thought this is my favorite movie of all time.

Heavy Metal is spellbinding yet rationally hard to defend. I like it more than any movie I’ve ever seen, but what intellectual case can be made for it? It’s embarrassing. There’s actually a story about a dweeb who visits a fantasy world, gains huge muscles, and has sex with hot babes. The art is sometimes excellent but more often workmanlike. The “groovy, man” tone of the writing hasn’t aged well. If “auteurness” is important to you, this lacks the personality of a Bakshi film or the polish of a Don Bluth. I have no idea who the individual directors are, or what they did before or sense. So what does it have that makes it special?

It has heart. Sincerity. It throws itself before the mercy of the court and receives a pardon. Heavy Metal elicits the nostalgia-drenched emotions of a beloved childhood film that I haven’t seen in twenty years, but I first saw it ten months ago. How’s that possible? How can you be Pavlov’s dog and salivate before you hear the bell?

“Soft Landing” is a stop-motion music video depicting a Corvette falling from orbit and landing in a field.

“Grimaldi” provides the framing device: a glowing green orb called the Loc-Nar (“the sum of all evils”) hypnotizes a young girl and shows her visions of the devastation it has wrought across time and space. These visions form the remainder of the film’s shorts. I hate it when words seem like anagrams but aren’t, and “Loc-Nar” is such a word.

“Harry Canyon” is the hard-luck tale of a New York cab driver in 2031 (ten years away!), driving aliens and vaporising mugs. He gets tangled up with a pretty young moll who’s on the run from the local goon squad (representative line: “Here I was, stuck with this beautiful girl. I knew she was gonna be nothin’ but trouble”). Might be mistaken as a parody of noir crime, but Heavy Metal is too earnest to parody anything.

“Den” is an adolescent nerd power fantasy. Describing the plot in detail would cause me to break out in pimples and start expressing strong opinions about D&D 5th Ed, so I’ll just say that it’s charming and pleasant, with a wonderful final shot. Den has the voice (but not the physique) of John Candy.

“Captain Sternn”‘s eponymous hero is in a jam. He’s on trial for 12 counts of murder, 22 counts of robbery, 37 counts of rape, et cetera. He thinks he has a plan to get off the hook (no, it doesn’t involve getting a job in the TRUMP ADMINISTRATION, ha ha), but as usual the Loc-Nar appears and ruins everything. Entertaining but lightweight, “Captain Stern” is the only segment that could have been cut without dramatically worsening the film. But it’s cute.

“B-17”, by contrast, is horrific. The pilot of a WWII bomber is flying home after a sortie, only to notice that everyone on his plane has died. Or have they? Gruesome and unredeeming, it’s similar to the Aldapuerta short story “Ikarus”, as well as the Twilight Zone episode “Terror at 20,000 Feet”. Great art, and a sense of doom as thick as squid ink.

“So Beautiful & So Dangerous” is about a babelicious fox/foxelicious babe who gets abducted by aliens and decides she’s into anal probes. I haven’t read the original comic but there’s clearly piles of story being left on the cutting room floor – we never learn what’s causing the mutations, for example. You have to leave room for tits and drug references, and this has plenty of both.

“Taarna” is an epic that closes off the film and resolves the story of the Loc-Nar. A peaceful people are on the verge of being slaughtered, and the warrior maiden Taarna rides to save them. It’s a heavily compressed version of a Moebius story, with continuity errors appearing at a rate of about two a minute (random example: how does Taarna get her sword back after escaping the pit?), but its flaws are obliterated by its grand, epic heft. The short evokes nigh-apocalyptic size: seeing this on a big screen must have been something. There’s some gorgeous panoramic shots of landscapes where every grain of sand seems to be animated – were computers involved? The final few minutes are a masterclass in color: bloody battles against an incarnadine sky, sickly green as the Loc-Nar makes its final stand, and a final shot of black splashed with faint colour: hope still exists, but you have to reach for it, into the stars.

Describing anything in Heavy Metal is a waste of time: all I can do is describe my reaction to it, which is beyond positive. Heavy Metal stands alone. It needs every concession ever made, and gets them. I don’t care if it objectively sucks, I don’t care if you think the comics were better: this is the best movie ever made by human hands.

This HBO documentary has enough creepy moments that it’s hard for a single one to stand out.

But imagine that your kid brother is living a real-life fairytale: he’s pals with the world’s biggest music star, hanging out at the guy’s mansion, eating ice-cream and playing videogames with him, hearing secrets worthy of Vanity Fair. It sounds unbelievable, like a tale from the playground’s biggest bullshitter (“I’m going steady with Miss America! No, you can’t meet her, she goes to another school!”) but this is actually happening to your brother. It’s enough to make you believe in magic.

Years later, you turn on the TV: a child like your younger brother is accusing the pop star of abusing him.

Wouldn’t your brain implode? The fairytale is gone, the wondrous years written over with a new and sinister context. Was this happening to your younger brother, all that time? Those holidays and fun-park rides and sleepovers…were they camouflage for this?

That’s the situation the brother of Wade Robson (one of this documentary’s two subjects, with the other being James Safechuck) found himself in 1993. It’s emblematic of how the Michael Jackson story has ended: too good to be true. I’ve heard alcohol described as a way of robbing happiness from tomorrow. Michael Jackson was cultural alcohol: the past was fun; but now the hangover has arrived. Although MJ may have also removed happiness from some peoples’ present, too.

I grew up in the 90s, when he seemed terrifying: a raceless, genderless skeleton with bleached skin and a face crafted from paper mache. I thought it was funny when they called him a “sex symbol”. For whom? Department store mannequins?

Had I grown up in the 80s I might have had different memories: the impossibly talented vocal ninja who (along with Quincy Jones) created large parts of the 80s as they are now remembered.

But even at the height of his career there was something strange about Michael, as though every camera was looking straight through him, missing large parts of the truth. In 1984 he swept up eight Grammy awards for Thriller (which had sold thirty-four million copies in twenty months), and was accompanied at the awards ceremony by Brooke Shields, then one of the most desirable women on the planet. He spent the evening ignoring her in favor of twelve-year-old Emmanuel Lewis, who sat on his lap.

Things deteriorated after Jones left his life. In the nineties he gained a reputation as a gifted but eccentric and even faintly sinister man – Howard Hughes with a surgically reconstructed nose. The tabloids (sensing skeletons in the Neverland closet) aggressively hounded him, and this became the narrative upheld by fans to this day: poor Michael Jackson, harassed by the media. Can’t they just leave him alone? If Leaving Neverland is true, the media didn’t chase him nearly hard enough.

It’s a documentary about narratives that are not exactly false or true but blends of the two: it doesn’t hide (for example) the fact that Safechuck and Robson testified that Michael Jackson never touched them during the 1993 Jim Chandler trial. However, it sets this in the context that they’d each been Michael’s favorite and they each wanted to be his favorite again. They wanted his approval, his love, and so when Michael told them what to say, they said it.

The documentary runs for four long hours. There’s a lot of biographical detail on two people you’ve probably never heard of unless you’re a hardcore Jacko defender with his entire legal saga pinned on the wall with red tape (in which case your opinions about Safechuck and Robson are probably negative). At first the homespun folksy stories of S&R’s childhoods seem pointless, but they quickly prove their worth: Jackson is such a massive figure that it’s easy for everyone in his orbit to seem like a 2D cutouts, as inhuman as the dancing zombies in “Thriller”. The director wants to make the accusers seem like people you know.

It worked. I believe them: their stories sound credible and are backed by a decent amount of evidence. Misremembering a date or a location is typical when twenty five years have passed. So is feeling affection for one’s molester.

There’s detailed descriptions of sex acts. A word of advice: if you don’t want to hear the sentence “in Paris, he introduced me to masturbation”, watch something else. Equally disturbing are the faxes Michael sent the boys, and the desperate manipulation he apparently tried towards the end to stop his entire house of cards collapsing.

The truth, as near as I can tell, is that Michael Jackson was probably a pedophile and his defenders were wrong. Their webpages and blog posts and Facebook groups (“TOP 10 PROVEN SAFECHUCK LIES!!! #MJINNOCENT”) are barricades built to defend an imaginary man who lives in their heads and nowhere else.

Where does that leave Michael Jackson in the year 2020? Is he “cancelled”? Is that even possible? There’s a psychological term called “splitting” – an inability to view people as having both good and bad sides. Michael’s strongest defenders clearly love his music, and certain aspects of his personality (philanthropy, generosity, etc) inspired them. Claims that he molested children represent a threat to that image of Michael – their Michael – and so they argue themselves into logical pretzels defending him.

It doesn’t have to be that way. You can still enjoy Michael’s music (and be inspired by the positive sides to his character) without retreating into solipsistic delusion. Michael was always good at making people become better versions of themselves, and we become better when we embrace the truth. Watch Finding Neverland and let Michael Jackson change your life one final time.