Despite being heralded as the last of “the Berlin Trilogy”, the sequence of albums Bowie while in tax exile, it sounds nothing like Low or “Heroes”. Whereas those were singular canvasses full of sound, this is just a collection of songs – some from Bowie’s top shelf, some from the bottom, and one from the wastebasket beneath it.

There’s a odd disunity within Lodger, it’s if nobody was quite sure of what they were doing. Maybe they weren’t. It’s no secret that the creative partnership of David Bowie and Brian Eno was falling apart by this point: Eno’s “compose in 17/8 while standing on your head and gargling noodles” tricks were growing irritating, and weren’t producing usable material. One stunt involved the backing band switching instruments. Another involved Eno drawing eight random chords on a blackboard and then having the band play whatever one he pointed at. Entire days were wasted in this fashion, producing nothing but countless hours of garbage. After Lodger landed on the charts with a desultory thud, Bowie chose not to work with Eno for his next release.

Which isn’t to say Lodger doesn’t have moments of greatness, which it does. But for the first time since Bowie landed in continental Europe, it has failures. Not lots of them, but they’re hard to ignore, particularly when one of them is up there with the most awful songs he ever wrote.

But let’s start with the best part: the three leading songs. “Fantastic Voyage” is a flamboyant, sashaying piece that reaches back to his Station to Station sound. Its lyrics connect mental illness and cold war paranoia. It’s a simple matter: we all have bad days (the Thin White Duke could attest to this), but national leaders have bad days, too…and they have the ability to destroy the world. This is the flaw in the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction – it relies on everyone in the world being rational and sane. What happens when nuclear weapons end up in the hands of a lunatic? The line “learning to live with someone’s depression” is darkly mocking. When the bombs start to fly, we might not need to learn.

“African Night Flight” is a paranoid freakout. It sounds a bit like a 33 RPM record of “Aladdin Sane (1913-1938-197?)” played at 45 RPM by mistake. Panicky, compelling stuff. “Move On” takes chords from “All of the Dudes” (a potential megahit that Bowie foolishly gave away in 1974 to nearly-forgotten glam act Mott the Hoople), and reverses them, turning a pop song into fascinating avant garde pop. As with “Heroes”, the lyrics seem laid on with a trowel, as if he’s parodying what a typical songwriter would write.

“Yassassin” is four minutes of drizzling shit. I can’t find words for much I hate it. It’s like middle school, when your teacher decides you need a dose of capital-c Culture and you get dragged off to see a kabuki show or something. Fuck off. I don’t want culture. I don’t want to broaden my horizons. Throw this song in the bin.

Side two begins with the musically average and lyrically excellent “DJ”. Bowie is at his cruelest and most sardonic here, he’s an egocentric disk jockey who thinks he’s king of the dance floor (“I got believers!” he crows). But as with Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy, we soon realise there’s something very wrong with him. DJs tend to be a bit “off”: they’re all performance, all illusion; no matter how full or how sweaty the dance floor gets, other people wrote the songs they’re playing. The crowd is grinding to Lady Gaga and Beyonce, not the guy behind the stacks, but many DJs lose sight of that. It’s a trade that attracts delusional narcissists.

“DJ” paints a picture of a man dangerously lost to fantasy, the real world slipping past his fingers like a shiny black record. He’s “(at) home, lost my job”, but that’s okay. It’s “realism”. Getting fired builds street cred, and he wouldn’t have it any other way. He says “I’ve got a girl out there, I suppose”…why are the last two words there? A repeated line in the chorus is “can’t turn around, can’t turn around”. Why can’t he turn around? Perhaps if he does, he’ll see that he doesn’t have quite so many “believers” as he thought. Perhaps he has no believers at all. Maybe it’s all an illusion, and he’s just a pathetic failure with no job and no girlfriend, spinning discs to an audience of nobody in his apartment. The song ends with the word “believers” skipping on its final two syllables. “Leave us…leave us…leave us…”

“Look Back in Anger” is a good track, inspiring Oasis and rendering them irrelevent in three minutes and eight seconds. Soon after, Lodger starts running into engine problems again. “Boys Keep Swinging” is fun and bouncy, but doesn’t stay with you. Nudge-nudge, wink-wink gaybaiting in the age of Jerry Falwell and Save Our Children doesn’t seem shocking, just hack. Then we get the ham-fisted “Repetition”, an unpleasant song about a man punching his wife around.

Album closer “Red Money” is a decent reworked track from The Idiot, although it sounded better with Iggy Pop singing it. More to the point, it’s now the second piece of old rope on a ten track LP (third, once you realise that “Boys Keep Swinging” has the same chords as “Fantastic Voyage”). Remember how Low and “Heroes” needed to make weight with covers and cast-offs? Oh, wait. They didn’t.

One can be too hard on Lodger. It’s another strong album, with lots of classic Bowie moments. But it was promoted wrong by RCA Records, and continues to be promoted wrong by fans to this day. It is not of a company with the two albums before it. The real Berlin Trilogy (according to to Bowie-ologist Chris O’Leary) is The Idiot (an Iggy Pop album hijacked at gunpoint by Bowie, and if you disagree you’re deaf), Low, and “Heroes”, with Lodger being a couple of footnotes. I agree, except “Yassassin” is a turd smear.

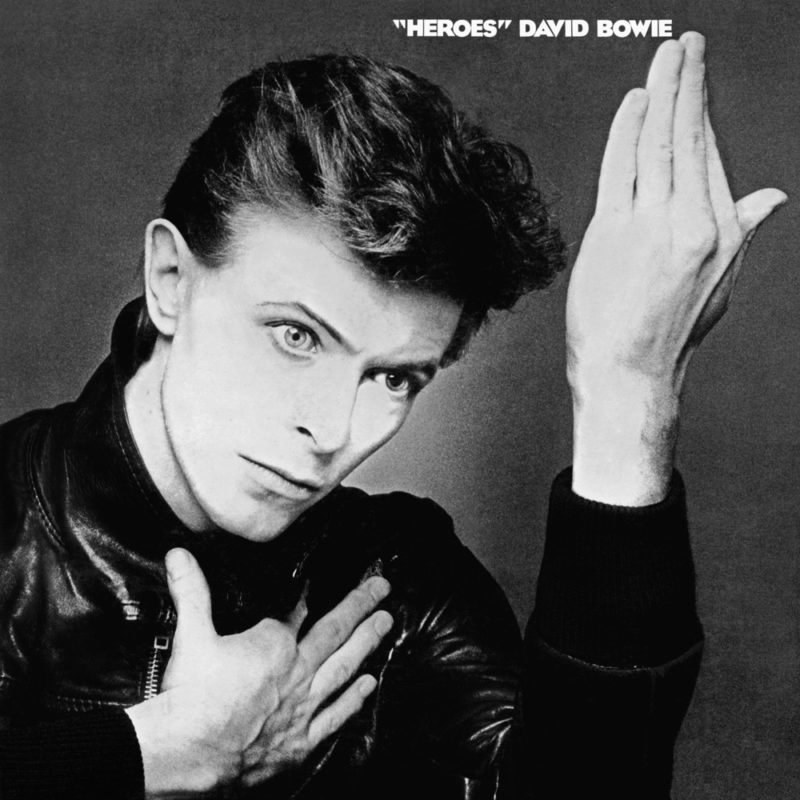

“Heroes” doesn’t equal the height of Low, but it’s an incredible album in its own way. Bowie created astonishing work in Berlin, and “Heroes” carved his name even deeper in the wall.

“Heroes” doesn’t equal the height of Low, but it’s an incredible album in its own way. Bowie created astonishing work in Berlin, and “Heroes” carved his name even deeper in the wall.

The opening track is snaky and serpentine, with Bowie spelunking down to the lower end of his range (“…gone wrong” slides to C#2, one of his deepest studio notes). “Heroes”‘ songs fall into two categories: the ones that make sense on their own, the the ones that make sense as part of “Heroes”. This is one of the former.

By contrast, track 2, “Joe the Lion”, is the latter. I can’t listen to it without the rest of the album: it sounds agitated and broken and gives the listener no relief at the end. But it does provide effective contrast for the krautrock-infused nostalgia of the next track: it’s like driving over a broken road, which changes to smooth blacktop.

The title song is the obligatory classic, which has survived overplay through massive sonic depth. There’s much to discover inside “Heroes”, between Carlos Alomar’s fill-in lines and Brian Eno’s electronic squawks. The song’s like an infinitely unfolding sheet of paper, containing yet more scribbles inside each unfurled fold. The lyrics are broad, and on the page sound faintly mocking, although no trace of this comes through on the record.

Functional harmonists describe music as a journey made of chords. When you listen to the tonic chord containing the key signature, you’re at home (in the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” this chord underlines “in the town…”). The subdominant chord is like leaving home to go on a journey (“…where I was born…”), the dominant chord is like arriving at your destination (“…lived a man…”) and then you might go home again back to the tonic (“…who sailed to sea.”).

Maybe my ear is bad, but little of “Heroes” makes sense when analysed in this fashion. There’s nothing that sounds like home, or a journey, or a destination. Notes swirl like squid ink, sometimes coagulating into chords, more often becoming pure texture. Even interesting. The album’s explorative nature is irresistable, even when it leaves the listener behind.

“V-2 Schneider” opens with air-tattered wailing, reminiscent of London during the blitz. The V-2s (German “Vergeltungswaffe”, “Retribution Weapon”) were long-range ballistic missiles, fired across the English channel at London, where they killed an average of two limeys per missile. The other side of the story was the 12,000 forced laborers who died in the production of the missiles. As with many purported Nazi superweapons, the V-2 was far more lethal to its builders than its targets. “Schneider” is “Florian Schneider-Esleben”, one of the founders of Kraftwerk: Bowie finally removed the letter c from his covert krautrock borrowings, making them overt.

“Sense of Doubt” is very dark, featuring a piano microphoned so that every note cleaves space with the power of an axe. A glittering synth line is introduced, as black as polished anthracite. I assumed this was Brian Eno’s work, but the song credits only Bowie. Much of the Berlin trilogy’s instrumental work was creating through procedural experimentation – the composer(s) drawing a card with instructions on it (“Use an unacceptable color”) and trying to attach a song to that scaffold. This isn’t unlike the process used by the Oulipo group to write books – although the Oulipists have yet to produce their Berlin Trilogy.

Traces of life stir in the shadow of this track. “Neukoln” is Bowie going “hey, remember when I used to play the saxophone?” and pairing it with yet more brutalist sonic architecture. His expressiveness seems like a plant weaving through cracked concrete.

The pattern of songs/ambience was used before in Low, which is part of why I prefer it. Even at its best, “Heroes” is retracing his own path, not forging a new one. The only difference is the final track, “The Secret Life of Arabia”, which is actually a song again. Maybe there is a journey to “Heroes”, but instead of in the chords, it’s in the songs. But there’s no sense of home when you follow those twinkling stars, just oddness and neurotic experiments. Or has home changed while you were away?

Keeping up with the Jones. After an artistically creative and personally devastating period in LA (full-cream milk, red peppers, and cocaine are a balanced diet, right?), Bowie went into hiding in Europe. Low is meant to meant to suggest “keeping a low profile”. He failed. Keeping a low profile would necessitate a bad album, and Low is simply unforgettable.

They “There’s old wave, there’s new wave, and there’s David Bowie” In a record store, they might say “there’s David Bowie, then there’s Low”. Nomimally the first of the so-caled “Berlin Trilogy” (despite parts of it being recorded in France), Low doesn’t quite sound like anything else he’s done.

Side A has songs, bending punk rock, art rock, . Bowie has seldom written better songs, and Eno’s technical wizardry makes the music seem otherwordly. This is most noticeable on “Speed of Life”, which has varispeeded delay that sounds like strobing flashes of light hitting the Hubble telescope from a distant cosmic object.

The songwriting is sparse and free. Entire songs are threaded together with simple ingredients: a single hook, or rhythm, or texture, but are all the more impactful for it. Lead single “Sound and Vision” has no words until the halfway point, and they’re just minimalistic automatism. No references to the Kabbalah or homosexuality. Just Bowie looking at blue light through his window, waiting for ideas.

“Be My Wife” surprises with familiarity, jarring you with a conventional verse/chorus pop song. Bowie was so good at being fake that there’s often a creepy, uncomfortable sense that he’s dropping the mask and momentarily sharing real feelings, knowing that nobody would ever know. The harmonica-driven instrumental “A New Career in a New Town” spins away the remaining grooves much as “Speed of Life” began them: in adventurous fashion.

Side A is an amazing achievement for Bowie, for Eno, and for rock. It is also Low’s worst side.

Side B deeply, profoundly well-realised, a haunting exploration of sound. It’s ambient music made jagged and broken, like a priceless Qianlong Vase smashed on the floor, allowing the viewer to find whatever beauty they may in the fragments.

People often refer to it as “the instrumental side”, which isn’t right, as only “Art Decade” lacks lyrics and vocals. But they’re brilliant, unforgettable pieces of music, and showcases just how much atmosphere Brian Eno could evoke with tape loops and a one-finger melody.

The dominant ambient piece is “Warszawa”, evoking a city of rust and memories, ancient fumes pouring from its skin. Futuristic Minimoog lines counterpoint church bells and religious chanting in a strange, brutal language from another world. It’s six minutes long: hermetic, cthonic, and almost impenetrable upon first listen. You have to peel it back like a palimpsest, and I’m still not sure I fully get it. David Bowie used to play this live. As a set opener, no less.

“Warszawa” was written by a four year old. Well, the first three notes, anyway. David needed to attend court to square away some matters from the Los Angeles fiasco, leaving Brian Eno to try and come up with something. Tony Visconti’s four year old son wandered into the studio, discovered the piano, and plonked out three notes – an A, a B, and a C. Suddenly inspired, Brian Eno dashed to the boy’s side and completed the melody. I don’t see Visconti’s son credited in the album booklet. The tyke should sue.

The album’s remaining pieces gently come down from this crescendo. “Art Decade” is chilly and still, its melodic ideas frozen like images under glass. “Weeping Wall” has very busy instrumentation, its elements sometimes clashing and other times working in harmony. “Subterraneans” is deep, slow, and forbidding. If the album was a day, this would be the deepest watch of the night.

There’s bonus tracks, too, if you get the right version of the album. “Some Are” seems like a marriage of the two halves of the album, while “All Saints” is extremely harsh – industrial ambient rock as corrosive as drain cleaner. I’ve heard rumors that “All Saints” was recorded a long time after Low, and indeed, it sounds very different in its production approach. You get a remixed version of “Sound and Vision”, which belongs in a bin.

“Heroes” doesn’t equal the height of Low, but it’s an incredible album in its own way. Bowie created astonishing work in Berlin, and “Heroes” carved his name even deeper in the wall.

“Heroes” doesn’t equal the height of Low, but it’s an incredible album in its own way. Bowie created astonishing work in Berlin, and “Heroes” carved his name even deeper in the wall.