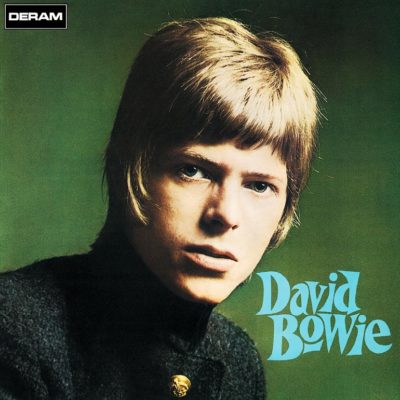

In 1967, David Bowie’s recording career began…and didn’t.

Well, it depends. What do you consider a beginning? Metallica’s first album is Kill ‘Em All, but that’s just a Diamond Head imitation. Their signature sound emerged on Ride the Lightning. That’s their beginning. The first Mad Max movie came out in 1979, but it’s just a violent exploitation film: the series truly starts with Mad Max 2. Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series begins with hallucinatory fragment The Gunslinger: but the story only truly takes shape with book 2, the Drawing of the Three.

First efforts are usually flawed efforts, contaminated by inexperience, self-doubt, and outside interference. They’re not “real” starts, any more than Michelangelo’s first cast-off lump of clay was his first sculpture. David Bowie probably existed by 1969, and certainly by 1970. But in 1967, the cards were still falling. Whoever this is, it isn’t him. Not yet.

David Bowie is musically bizarre in light of his later albums: fourteen show-tunes for shows that never existed. It never misses a chance to be quirky, chirpy, and naff, the songs are bedecked with organ and keyboard parts, and Bowie (who had just turned twenty) does a fine job of sounding like an elderly sex pest.

It draws aesthetics from music hall, a venerable tradition that was fading in the 1960s, and is now utterly unendurable to modern listeners. I have never met a person who likes music hall. Have you? Do they exist? I’ve met people who claim they’ve seen aliens, but the elusive music hall fan still avoids me.

Music hall featured (and relied upon) stage shows and live performances: it may have been the the 19th century’s equivalent to the music video. The album suffers for its lack of a visual element, and feels a bit flat. No doubt Bowie had planned out short films and mime performances and dancing bears for each one, but then the album flopped. The songs are like colorful little parrots, their plumage covered by a dropcloth. We can hear them well enough, but they’re less charming without their bright feathers.

The music is mostly in good order. Even at twenty, Bowie knew how to put a song together. “Love You ‘Till Tuesday” strides into its chorus with a ritardando that made me say “nice” out loud in the middle of an empty room, which was embarrassing. “Sell Me A Coat” is a catchy ohrwurm, hand-tailored for the single release it never received.

The lyrics are a high point, although they’re definitely more interesting than good. Music hall was “low” entertainment, attracting people gate-checked out of polite society, and it played music to match. Bowie takes full advantage of this and just lets it all hang out, writing anything that will scan, no matter how stupid or awful or anti-social.

“We Are Hungry Men” is a humorous science fiction dystopia about a dictator’s solution to overpopulation. I laughed at the line about people being allotted a cubic foot of air to breath, although the part about China someday having “a thousand million” people didn’t age well.

“She’s Got Medals” is Bowie’s first song to deal with transvestism (“Passed the medical! Don’t ask me how it’s done!”), and “Little Bombardier” takes a nasty turn into pedophilia. The closing track is a spoken-word piece called “Please, Mr Gravedigger”, which tightrope-walks between being ludicrous and genuinely horrific.

There’s a lot of filler and half-songs (and quarter-songs), and I won’t pretend I want to hear things like “Come and Buy My Toys” ever again, but the songs are so diverse it hardly matters. They’re presents under a tree: if you don’t like one, you try your luck with another.

Bowie did the same thing – you can see many possible futures for him, refracted in the facets this strange, strange album. A mime? An actor? A vaudeville hoofer? A hippy? The genius who wrote Hunky Dory? I’m glad he chose the future he did, because it easily could have gone another way. In June 1967, an album came out that would change the face of pop forever. This, however, is not a review of The Beatles Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, but the first David Bowie album.

No Comments »

This song was created as part of a prompt: it’s based around the movie The Guest, directed by Adam Wingard and starring Dan Stevens.

The first half of the movie (before it descends into Jason Bourne cliches about supersoldiers and government agencies) is genuinely frightening. A man shows up on the doorstep of a family that has lost a son in the Afghanistan war. He claims to be a soldier, and a friend of their son.

He’s affable enough, but there’s something not right about the stranger. He’s intrusive, and oddly persistent. Nothing about his backstory adds up. Brutal violence lurks in his smile – he’s a human guillotine, with the guard-rail filed down to a hair. What, exactly, does he want?

The movie draws from westerns, particularly the darker, subversive breed pioneered by Clint Eastwood. In it, the Man with No Name rides into town…and he’s somehow even more terrifying than the bandits. He’s ostensibly a good person, but where did he come from? Why did he have to leave? What are his motives? And God help us…what if he’s not actually good?

I tried to reflect this in the horizontal motion of the piece. We begin in jarring 7/4 time, and the G mixolydian melodies attempt cloying sweetness and instability. The family at the start has lost a son, and although they’ve found a rhythm it’s not a good or satisfying one. Nothing like the life they had before.

Then the broken half-rhythm is invaded by knife-attacks of backmasked guitars and neotonal piano flurries. Then the ambiguity about the song (and the soldier) vanishes, ripped away like a mask, and you wonder why you ever thought there was ambiguity to begin with.

I’m not super happy with this, but it’s the best thing I’ve managed yet from a production and mastering perspective. Working around technical limitations sucks. (I ended up with hats chained to the snare bus somehow, limiting percussion possibilities.) My brain still thinks in 4/4 even when I’m writing 7/4 and 6/4, and some of the piece suffers for that.

At one minute and fifty-one seconds, this is a short-staying Guest.

No Comments »

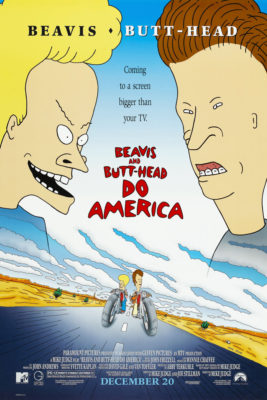

Beavis and Butthead wander around America, being so stupid that they’re almost immortal. The show itself works the same way. It’s one-dimensional to the point of being immune to criticism: everything is right there, on the surface, an inch from your face. There’s nothing to “unpack”. There’s no message, or subtext. Merely by reading the title, you’ve plumbed its deepest depths.

Read contemporary reviews and you’ll see flop-sweating critics trying to find nuance in a show that doesn’t appear to have any. What can you say about Beavis and Butthead? That it’s a show about two idiots? Is that it? Is there anything deeper going on at all?

Maybe. Let me attempt an explanation:

The show is an extreme parody of Generation X nihilism. The 80s became the 90s, the Berlin Wall fell, Nirvana’s Nevermind came out, and millions of young people collectively decided it was uncool to care. Your clothes? Flannel and torn jeans. Your career? Skateboarding, or playing guitar in a local band called Turdsplatt. Your death? Late twenties, overdosing on some fashionable drug (probably heroin.)

Generational contempt hit an all-time high. Parents in the 60s thought their kids were commies, parents in the 80s believed their kids were devil-worshippers, but at least those things require initiative. Now, kids just sat in front of the TV all day, growing dumber and less curious by the second, as the Ozone layer burned and bombs pounded Vukovar. For the first time, the youth weren’t scary, just embarrassing.

Yes, this stereotype was unfair. The most famous Gen X’er, Kurt Cobain, was industrious, introspective, and mentally ill, not an apathetic slacker. But the lack of fairness is sort of the point: Beavis and Butthead are caricatures from baby boomer imaginations, rendered in full ridiculousness. Mike Judge isn’t mocking teenagers, he’s mocking their parents. “Look at this. Is this really what you believe your kids are like?”

But what about the movie?

The story begins with Beavis and Butthead noticing that their TV has been stolen. After pronouncing weighty judgement on the situation (“this blows”), they set out on a journey to find a new one, road-tripping across America and snickering at every sign on the interstate (“heh heh…Weippe…”)

They’re soon wrapped up in a drama involving government agents, a deadly bioweapon, and the President. The specific details are unimportant, since Beavis and Butthead successfully misunderstand or ignore every single thing that happens to them (no mean feat, as one of them is an elbow-deep cavity search). There’s funny jokes, and even some pretty good animation (particularly a peyote-tripping scene created by Rob Zombie).

Roger Ebert enjoyed the film, but noted his difficulty in telling the two central characters apart. I can confirm that they are distinct: Butthead is taller, has dark hair, and is somewhat more intelligent. He wears an AC/DC shirt, which I always thought was a little off (Metallica is fine, but AC/DC was a band your dad listened to). Beavis is an anarchic force of chaos, barely held in check by an occasional “shut up, buttmunch” from his domineering friend.

B&BDA is 25 years old, and many of its cultural references seem dated. In another 25, it will need a Rosetta stone to be understood. It came out in 1996, and although it made money there wasn’t a sequel. The show was cancelled in 1997, and for years it existed in a weird dead zone: too old to be relevant, but not old enough for a nostalgia-fueled comeback. That happened in 2011, although the show will probably never command the level of attention it had before.

B&B don’t really work when you transplant them into modern times. In 2018, it’s old people who sit around watching TV all day, not kids.

But some parts of Beavis and Butthead haven’t aged, and some that did really shouldn’t have. When government agents try to track the duo down, they use a fax machine. Beavis and Butthead are stupid, but there are worse things. There is intelligence paired with malice. They should be glad that they weren’t living in 2018, smartphone addicted rather than TV addicted, with the NSA understanding them far better than they understand themselves.

No Comments »