Oscar Wilde espoused an idea called kaloprosopia, creating oneself as a beautiful character. “Life has been your art. You have set yourself to music. Your days are your sonnets.”

Discussions of who you really were irrelevant to Wilde (and still are, I guess, as he’s dead). People misunderstand everything anyway, so why not be misunderstood as something interesting? Turn yourself into the Taj Mahal, which has so much paint and white marble that nobody can believe there’s plain sandstone underneath.

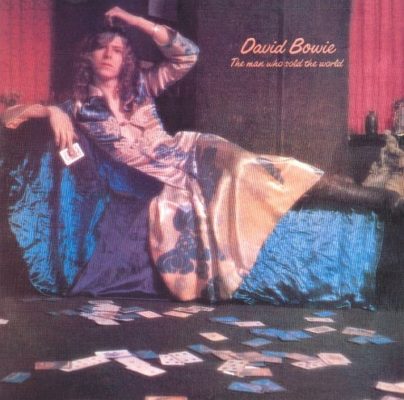

I don’t know to what extent Bowie liked Wilde. All I know is that he appears on this album’s cover in a dress, and in two more years he’d declare himself gay in the pages of Melody Maker, and twenty years after that he’d declare in Rolling Stone that he was never gay and it was all a publicity stunt, and thirty years after that his former wife Angie would allege to a biographer that she’d caught him in bed with Mick Jagger. Reality? Truth? What’s that?

By 1970, Bowie’s career hadn’t amounted to much. A minor hit with “Space Oddity”, and a follow-up called “The Prettiest Star” which sold 800 copies. Commercial rejection caused him to throw caution to the wind and write some of his most bold and startling material. The Man Who Sold the World is a heavy metal album, recorded several months before Black Sabbath’s Paranoid, an album it nearly matches in riffs and intensity.

Unlike Space Oddity, he had a tight band around him now (an early version of the Spiders, lacking only Trevor Bolder on bass): particularly Mick Ronson, who nearly dominates the album with his guitar work. Tony Visconti was learning a trade at a rapid pace, and his production work almost becomes another instrument.

“Running Gun Blues” was a track Bowie never seemed to keen on performing live after he got famous, for whatever reason (“I’ll slash them cold, I’ll kill them dead! I’ll break them gooks, I’ll crack their heads!”) but it rocks hard and has some strong vocal work. Terrible lyrics aside, it’s a notably early entry in the “crazy Vietnam vet” genre; the album was recorded only a few months after word of the Mai Lai massacre arrived in the United States.

The album doesn’t have one closing song, it somehow has two. “The Man Who Sold the World” is the record’s catchiest cut. “The Supermen” is apocalyptic and Wagnerian, with Bowie shrilling out his lines like an Etonian robot Hitler. Either song would work as an album closer, and it seems only a trick of fate put “The Supermen” last.

But the tracks are like planets orbiting the sun that is “Width of a Circle”, an eight minute epic that predates Ronson’s entrance to the band, although I cannot imagine anyone else playing it. The song is driven by massive riffs, and lead breaks that burn like excoriating fire. Apparently, this became Bowie’s “costume change” song in the Ziggy Stardust era. He’d leave the stage entirely, allowing Ronson to solo over “Width of a Circle” for up to ten minutes!

The lyrics are pretty interesting, fusing the Rolling Stones’ sales pitch for Satanism with homosexual innuendo. I don’t know if the “circle” in the title is a reference to Dante or a something even more nefandous, and that way it will stay. As usual Bowie’s a little cleverer than the Spinal Tappery would suggest: “prayers were small and yellow”…why “yellow”? Cowardice? Or a reference to the yellow book that corrupts Dorian Gray (another Oscar Wilde connection)?

The Man Who Sold the World is full of amazing moments, and it’s a worthy start to a legendary run of albums. Ironically, Bowie himself wasn’t totally on board for it. He’d just gotten married (so the story goes), and beyond a few songs that predated the marriage, his partners in glam had some trouble getting him to write and record. The marriage ended in 1980, but The Man Who Sold the World has lasted and lasted. It’s an enduring classic, and still only his beginning.

No Comments »

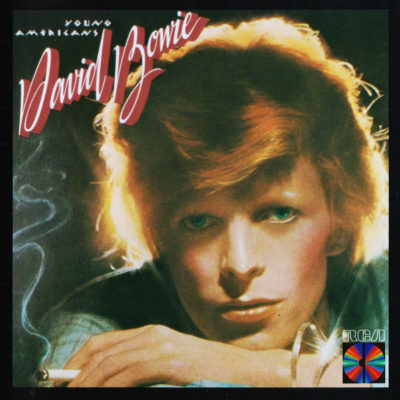

My least favorite of the classic DB albums. I don’t like soul music much, and the songs tend to rely upon “call and response” vocal patterns more than actual melodies, which is a shame.

But it’s still special, and contains two of his finest songs. Bowie (at least at this stage of his career) didn’t compromise much: once he picked a style to explore, he carried it through to its conclusion (although whether said conclusion was “The Laughing Gnome” or “Station to Station” depends much on the year and the drugs he was taking). Young Americans represents a total break from the past. It would have bee easy to throw in some riff-driven rockers so the Ziggy Stardust fans have a lifeline, but Bowie rejected any last vestiges of the glam rock that made him famous.

Anyway, amazing song number uno: “Win”. The tone is tender and comforting, propelled by an exposed but deeply affecting vocal performance. I like “Golden Years” a little more, but between the two you have the best work he ever did in this style.

The Beatles cover “Across the Universe” misfires, though considering it also misfired in the Beatles hands, this is probably due to it being a bad song. The “nothing’s gonna change my world…” part remains bewildering: it always makes me think that the singer forgot the vocal melody in front of the microphone and is clumsily ad-libbing a new one.

The song existed as bait to attract John Lennon to the studio, and this gave us the second of Young Americans’ great moments (and a rare #1 hit): “Fame”. The song opens with brass playing a pair of 3/4 bars. The melodies seem to bloom in the air like flowers: their promise false.

The rest of the song is jittery and claustrophobic, consisting of yelped vocals over a sparse rhythm section. Carlos Alomar’s guitar riff is fascinating, jabbing you so quickly and sharply that it seems to penetrate vital organs. If “Fame” was a painting, it would be pointillism. Lennon’s guest contribution is to double the vocals – hitting you with David’s lyrics in stereo.

The rest of the album does the job to varying degrees. The title track (as with the album before it) ends up being kind of a non-event. It sets the tone, but doesn’t really. I quite enjoy “Fascination”, although I miss the heavy riffs and melodic singing.

One dud. Two amazing songs. Bowie would find that America aged him pretty fast, at this stage of his career he produced exceptional work wherever he lived and worked. A pretty amazing accomplishment: we’re watching Bowie jump into empty space…and land on his feet.

No Comments »

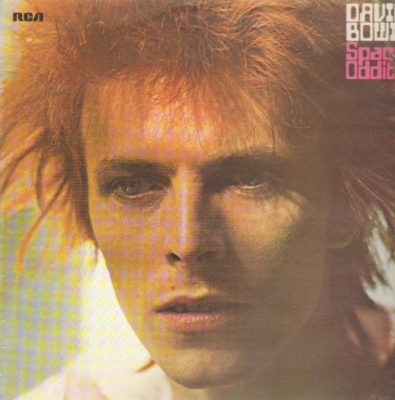

The events of the future are unknown, but The Future is an old friend: we’ve seen it come and go before.

First, new horizons appear. The lookout in the ship’s crow’s nest sights a new continent. Astronauts witness the dark side of the moon. But then the horizons blacken. The new continent is despoiled and pillaged. The moon asks the astronauts “you’re here. Now what?” The unknown turns ugly very quickly, as a piece of paper burns from the edges in.

A theme in science fiction (emphasized in the New Wave of the 1970s) is that we might not know what to do with the discoveries of the future: that our wings will burn away, and then we’ll fall. Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey took a less (or perhaps more) pessimistic approach, the future will change us so that we cannot fall. Evolution will alchemize us: the primitive shaggy apes are doomed, and though their descendants will succeed in the new world, they are not their descendants. Will we live or die in the future? Maybe it’s not simple. Maybe we’ll be different.

David Bowie saw the film while stoned, and it excited him terribly (interesting coincidence: the astronaut in the film is called “Dave Bowman”). His career was bouncing along like a dead cat at the time – failed bands, a dead-on-arrival album in 1967, and no real musical identity. His manager Ken Pitt was wearily cobbling together a promotional film (the unreleased Love You Till Tuesday), and he needed a filler track. Bowie wrote “Space Oddity”.

Forty four years later, it is Bowie’s signature song. It was performed in space by Chris Hadfield, four hundred kilometers above the earth’s surface. Unlike the apes, the humans, and Bowie himself, “Space Oddity” might never die. It has been selected for quasi-immortality. Nothing about the song makes sense. It’s a filler that will live forever; a tonally complex piece (with fifteen different chords) that can be strummed in basic outline by any starting guitarist; a musically indecisive song (neither sounding like folk or rock) that captures an era and a career. I’m still not sure what to make of it, but clearly we have to make something. It will outlive us, too.

The song’s minor success upon release (it was used by the BBC to score footage of the Apollo 11 moon landing – nobody seems to have realised that the song ends with the astronaut stranded in space!) led to a rushed album, initially self-titled, then rebranded as Space Oddity.

It’s not an unreserved classic. It’s confused at times, as if part of it still exists in imagination, and was imperfectly drawn into reality. The songs are mostly longwinded and complex, and the band doesn’t sound as tight as it needs to be. Tony Visconti’s solution was to slather everything in reverb and room noise, leaving Bowie’s vocal track to hold things together.

Although there’s only one outright bad song – the hideous “God Knows I’m Good” – it’s a frustrating listen at times, sometimes underdeveloped, and sometimes over-egged. Tracks like “Letter to Hermione” are so thin they can hardly stand upright, while “Unwashed and Somewhat Dazed” and “Cygnet Committee” struggle not to collapse under their weight. I want to run a butter knife over it, and smooth all the clumpy parts.

But Space Oddity is obviously a start for him. You can see where “Cygnet Committee” ends and “Savior Machine” begins, for example. There’s moments of real artistry: “Memory of a Free Festival” begins as a pile of indistinct musical fog, and just when you’re good and lost, a ship’s prow pierces the mist. You can hear the song make sense of its own confusion, and it’s one of the finer moments of the album. The album’s lyrics are mostly confessional in nature, which isn’t something we saw a lot of before or after. A lot of it’s about disillusionment. “Letter to Hermione,” “Cygnet Committee”, and “Wild-Eyed Boy from Freecloud” are kiss-offs to various relationships and social cliques Bowie was a part of.

Although it lives in the shadow of its very famous track, there’s much of interest here. I would not recommend this as a first Bowie album for anyone, and it might be best as their last: when one’s deep enough in the game to wonder where he came from and how he got to the present. If you want evolutionary steps, this is where we see vestigial legs appearing on Bowie. It’s very spacey, very odd, and very worthwhile.

No Comments »