In my review of Rock & Rule, I stated that it’s an adult film with no adult content.

This is not true; I saw an edited cut. According to the Rock & Rule wiki (??!), a version exists featuring brief nudity from Debbie Harry’s character, Angel. (Described below by an anonymous superfan, who gets way too into it. The Zapruder film wasn’t this obsessively analyzed.)

For most of the film, Angel wears a conservative but stylish red blazer over a black top with matching black pants, boots and a gold belt. After Mok enslaves and drugs her, she is forced to wear a very skimpy outfit for her involuntary performance at his concert. The outfit is a dress with a bare back and a front narrow enough to expose the sides of her bare breasts. The lower half of the dress is two fabric panels in the front and the back divided by slits up to her pelvis on either side, exposing her legs to the top of her hips. Also, Angel is not only going in her bare feet, she also isn’t wearing anything underneath her dress. We can see she’s bare underneath when the breeze periodically causes the fabric panels to lift, exposing her bare tush and the creases of her pelvis. This especially happens when she is singing to the demon and the back panel of her dress flips up, revealing her bare bum.

Can the coast guard mount a rescue mission for this man’s keyboard? It’s clearly drowning in its operator’s drool. Additional credits to society chime in the comments.

Based on her haircut, general appearance, it looks like they actually modeled her at least somewhat on Debbie Harry, who provided her singing voice.

Nothing gets past Sherlock here.

Angel’s brown” fur is actually her skin. After all, “fur is skin” exists according to TV Tropes & Idioms. So her sexy, thick, buxom, toned body is exposed.

A compelling argument, backed by citation. Can I suggest a career as a lawyer? You’ll be spending a lot of time in courtrooms either way.

Yeah, I think she and would get along well to being friends and having fun as girls. Her natural personality reminds me of a lot of the I usually hang out with. You rule Angel girl!!!! <3 :)

You shouldn’t think that, because Angel’s not your friend, or even a real person. She’s a cartoon mouse. Parasocial fixations on fictional characters are unhealthy, and you should make some real friends.

By the way, reading the heart ASCII <3 requires that you tilt your head to the right, and the smiley emoticon :) requires a tilt in the opposite direction. When the two appear back to back, you’d technically have to whiplash your head 180 degrees to read the text. Pretty painful, and if you did it fast enough, it might even prove fatal.

This could be used as an assassination method. Copy and paste “<3 :) <3 :) <3 :) <3 :) <3 :) <3 :) <3 :) <3 :) <3 :)” into an email, send it to your enemy, and see if they snap their spine. Or maybe that’s not how it works, maybe you’re supposed to imagine that the smiley is tilting its head. Can smileys be killed this way? Let’s try. :) :( :) :( :) :( :) :( :) :(. There. I just rocked and rolled it to death.

No Comments »

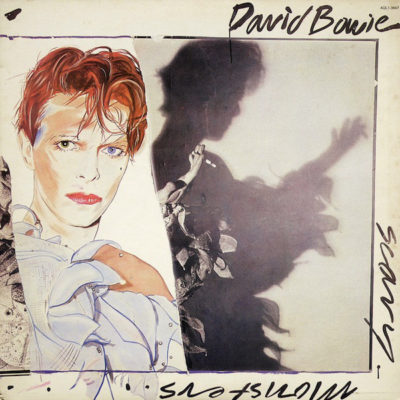

Scary Monsters and Super Creeps is Bowie’s Except Album, meaning it often appears along with the word “except”. “Bowie sucked in the 80s, except for Scary Monsters“. “Bowie was never good when he tried for mainstream success, except for Scary Monsters“, and so forth.

It’s also often spoken about in the same sentence as “scary” and “monsters”. Though that’s less surprising, since that’s the name of the album. It would be strange to talk about the album without mentioning its name, although it would be a fun challenge to do so (and also without identifying it another way, such as “the Bowie album from 1980”). Kafka led a man to the executioner’s block without ever mentioning his crime. Could you arrange words in such a fashion that a reader understands the music, without ever actually being made aware that the album exists?

Scary Monsters is about decay. Not decomposition, not morbidity, just…things falling apart, in a general sense. It’s an album about the crack in your ceiling, and the verdigris embroidering your bathroom floor. All the things you’ve been meaning to fix, even as they advance to an event horizon where it’s not worth the bother.

Bowie assembled some of the finest guitarists to ever set plectrum to string, and made them play sloppily. Vocals are deliberately flat, or mangled oddly in the mixing room (the heavy tremolo rattling the chorus of the title track both disturbs and fascinates). The lyrics discuss fashion and aging, yet they all seem to be about the House of Usher. The building is tumbling down, we’re caught inside it, and we can never leave. Bowie sings about disillusionment and weariness, his voice cracked and broken. None of his albums – not even Aladdin Sane or Outside – evoke this kind of genteel neglect.

“It’s No Game, Pt 1” opens the album in thuggish fashion. Someone took the song, punched it around, and gave it a black eye. Fripp’s guitar part swirls like stagnant water, the drums kick out at you, and it’s interrupted by outbursts of Japanese female vocals, as though someone spliced in the hourly Harajuku traffic report. Although this is the closest solo Bowie ever went to punk rock, it’s cerebral and calculated beneath the blood: more like Public Image Ltd than the Sex Pistols.

Other tracks document various vanishing trends in Bowie’s music. One of the last great Bowie epics (“Teenage Wildlife”) can be found here, as can shorter but equally memorable cuts like “Up the Hill Backwards”. Be sure to get the version with the bonus track, “Crystal Japan”, which was written to score a TV ad for a sake company (of all things) but dredges up strong memories from the Brian Eno years.

“It’s No Game, Pt 2” is a slower and less enthusiastic reprise of the first part. There’s an old Hollywood joke: at eight in the morning you’re shooting Citizen Kane, at eight in the evening you’ll settle for Plan 9 From Outer Space. This song captures that kind of exhaustion and weariness, freezing it under glass.

This album has a reputation as a Bowie threw away most of his artistic pretensions and went fishing for hits. Happily, he caught one (“Ashes to Ashes”). Even more happily, the reputation is wrong: he didn’t throw his artistry very far after all. There’s louche experimental moments all over Scary Monsters. This is the rarest thing: an artistically successful commodity. It’s also one of his most consistent and listenable works. Clearly, the future was bright. He would not put a foot wrong in the 1980s.

No Comments »

It’s an odd idea to write books for people who never read them, but it’s worked for Mr Reilly so far. Ice Station is a brutally fast-moving action thriller novel that seeks to be a movie on paper – probably one directed by Michael Bay.

Like all of Reilly’s work, it barely exists as literature: it’s a screenplay with cover art and an ISBN number. The typical paragraph is one line long. The typical adverb is “suddenly”. Descriptions are sparse and visual. There are comic book sound effects whenever someone has their head blown off, which is often.

The book stars US marine Shane Schofield, whose unit has been dispatched to a remote Antarctic research station (are there any Antarctic research stations that aren’t remote?). A metal object has been discovered in a 100 million year old layer of ice: it could be an alien spacecraft. Since nobody “owns” Antarctica, a number of foreign nations are attempting a snatch and grab mission to seize the discovery.

We get about forty pages of backstory (meaning, Reilly setting up dominoes so they fall in the most destructive way possible), then the action begins and never stops. Schofield ends up fighting French soldiers, British soldiers, his own unit, the environment, killer whales, frostbite, etc,

You could probably build an Antarctic research station from the combined metal of all the ejected bullet casings in this novel. The story’s so addictive and streamlined that it’s hard not to read in one go, in fact, experts say the average person reads at least seven Reilly novels per year in their sleep without realising it.

The obvious movie cliches appear: a nerdy scientist who plays Captain Exposition, a cute little girl with a pet, a traitor on the team, a rushed romantic subplot, etc. Reilly doesn’t know how to write anything except action, but it’s amazing action. A high-speed hovercraft chase and a tense battle in a killer whale infested pool particularly stick in the memory. He also knows the media his audience might be familiar with, and includes nods to Die Hard, Tom Clancy, Michael Crichton, and the X Files in all the right places.

Reilly’s plotting is often cited as incompetent, but it’s actually entirely competent – it’s just geared to something other than making perfect sense. Basically, whenever “cool” clashes against “logically plausible” (or “physicially possible”) cool wins. This is the Rosetta Stone to making sense of Ice Station.

For example: Schofield breaks a rib in this story. In the real world he would have great difficulty accomplishing some of his later feats in the story (such as swimming hundreds of meters), but that’s irrelevant. Reilly is the God of Cool, and sometimes he allows the mortals in his universe to break the laws of physics. Schofield needs to keep doing cool stuff, so he does it with a broken rib.

It would be funny to read a “self aware” hero who knows he’s in a Reilly novel (think Scalzi’s Redshirts). He’d try to stay alive by doing the most outlandish and ridiculous things possible. He’d dash to the nearest pet store and buy a cute dog. In fact, he’d wear body armor made of cute dogs stapled together: nobody would dare shoot a bullet at him. He’d also hire a plastic surgeon to make him look like an A-list Hollywood actor (Schofield’s physical description is a dead-ringer for Tom Cruise).

A realistic depiction of the story’s events would also make an interesting novel. Legally, Antarctica is not an ownerless waste, it’s a condominium – jointly owned by twelve nations. If an alien spacecraft was discovered, nobody would send special forces to capture it. Such a “capture” would be worthless – a huge metal object can’t realistically be transported or removed by twelve guys with guns, and it would stay in Antarctica, no matter who wins the shootout.

In Ice Station a group of bad guys hatch a plan to free the spacecraft (if that’s what it is) by detonating thermonuclear charges, creating a new iceberg with the spacecraft inside it, and steering the iceberg north to their sovereign territory. But then it would be pretty obvious what’s going on, and since the Antarctic treaty forbids the detonation or testing of weapons, you might as well declare war with half the world.

I read Ice Station at fourteen (the correct age), and it remains my favorite of Reilly’s work. It’s efficient, the prose is as tight as the wires in a Hong Kong action movie, and it avoids the goofy GI Joe cartoon feel that spoils some of his later work. It’s obviously nobody’s idea of a literary treat, but you don’t need spaceships to fly, and Ice Station proves it.

No Comments »