Torture. Moral issues aside, does it work?

You have a man in your care, with a fact in his head. Can you torture it out of him? Maybe. But he hates you, because you’re torturing him, so he might tell you the fact in an incomplete or misleading way. And couldn’t you have gotten the fact from him using another method? Consider Knightian uncertainty: you don’t know what you don’t know, and a well-treated prisoner might divulge additional facts that he didn’t have to. A tortured man never will.

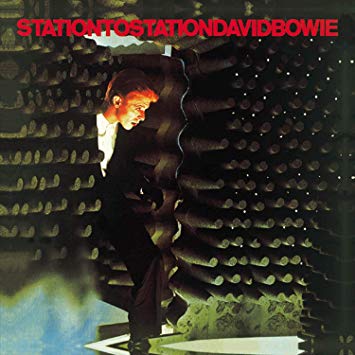

Defenders of torture, of course, have a slam-dunk defense of their art: that it created David Bowie’s Station to Station.

It contains the greatest Bowie song ever (“Station to Station”), the greatest Bowie lyric ever (to be discussed), the greatest Bowie pop song ever (“Golden Years”) and the greatest opening chord on a Bowie song ever (Carlos Alomar’s Am7 on “Wild is the Wind”). I advise listening to this album soon and often. It’s amazing. But do be advised: it was created through torture.

It was created during a horrific period of Bowie’s life, where the drugs begin taking the man. Alone in a mansion in Benedict Canyon, Hollywood, he went insane. It’s all there in the biographies: storing his piss in jars, seeing UFOs, to see his spectral aura, exorcising Satan from his swimming pool, believing that the Rolling Stones were sending him messages in their album covers. Some of these might be myths, or embroideries on the truth. Bowie himself is no help. He says he doesn’t recall making Station to Station at all.

Did he create Station to Station? The album isn’t a pathetic drooling mess of needle injection sites and discarded cocaine twists, as most “druggie” albums. It sounds tight and professional, brightly mixed, with some of his best top melody singing. This is the work of a man at the peak of his power.

The title track is, well, a perfect song. It runs for ten minutes, and you want it to keep going. Train noises are heard, wandering across the stereo field. The train is moving, and we’re not on it. The blurring steel hammer disappears over the horizon, and a loping 2/2 alla breve vamp takes its place. It sounds tight and smouldering on the record, but gigantic live. One of the downsides of the whole Bowie-being-dead business is that he won’t ever play “Station to Station” again. Listeners are free to imagine him in their bedroom, miming to the song while wearing a dress, but somehow it’s not the same for me.

Halfway through, the song erupts, blasting out lyrical and sonic incalescence. “Once there were mountains on mountains!” Cmaj, Dmaj, Emaj, Amaj, Emaj, F#min. The great lyrical moment happen here: “It’s not the side-effects of the cocaine! / I’m thinking that it must be love.” Listen to his difficult, strained delivery, and these two lines crackle with the energy of broken power cables. The world turns beneath him, mountains collapsing to rubble. Just for a moment, David Robert Jones from Brixton is Zeus, hurling thunderbolts. His mind sounds smashed to pieces, reassembled, but somehow stronger and purer than it was before. This signals the final shift in “Station to Station”. The band spins out of control, as if a life-rope’s been cut, and the remaining five minutes are spent in a long vamp built from repeated declamations of “it’s too late”.

Contrary to popular belief, Station to Station has other songs. “Golden Years” is an extremely catchy and well-realised single. The performances aren’t quite as tight as, say, Low (listening to the vocals in isolation reveals that he’s a bit loose with his timing) but the total effect is one of sublime perfection. “TVC15” and “Stay” are similar in tone: jittery, anxious, and funk-driven. “TVC15” is apparently based on a nightmare Iggy Pop had of a TV swallowing his girlfriend. “Stay” is Carlos Alomar earning his paycheck, featuring a jagging main riff with a ninth note thrown in there. The words of the chorus are near incomprehensible word salad: a good evocation of a man who has turned his mind into an MC Escher painting. “Wild is the Wind” ends the album on a plangent note. A jazz ballad, with a wonderful misty and distant feeling.

“He put all of his effort into his art” is a cliche vapid, but it takes on a darker shade: we’re not supposed to put all our effort into one thing. We’re supposed to have lives. We’re supposed to be normal.

I once read a French horror comic (I can’t remember the name) about a race car driver, with a special bond to his vehicle. With his fuel running out, and the great race of his career on the line, the vampiric car sucks his blood out of his veins and burns it, winning the race and hurling a corpse across the finish line. That sums up Station to Station. The stunning artistic heights were achieved at great personal cost to Bowie. It’s a thumbscrew and a rack on a vinyl LP.

Albums cathartic to artists are often dull to listeners, and this is the reverse: another Station to Station might have killed him. After making this album, Bowie fled Los Angeles. As if he himself was the demon in the mansion, and he’d performed his own exorcism.

No Comments »

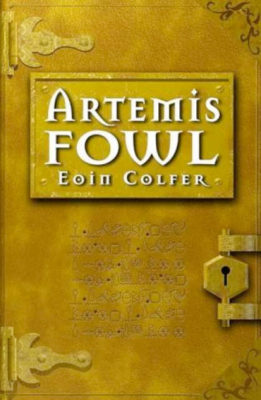

This book arrived bedecked in heraldry as The Next Harry Potter (every children’s book released 2000-2005 was officially The Next Harry Potter, just as every modern David Bowie album was “his best since Scary Monsters”). It doesn’t live up to that, and doesn’t want to: it’s something else entirely. It hardly feels like a book for children. The action is fast and kinetic, the writing is as taut as the wire-work in a Hong Kong action film, and the concept is pretty clever: a mixture of Lord Dunsany fairytales and Die Hard.

The plot sounds outright stupid in summary: like it was created by a desperate screenwriter in the 8th season of a show. “There’s a twelve year old supergenius called Artemis Fowl, and he’s also a criminal mastermind, and has a scary bodyguard who kicks ass like Bruce Lee, and he discover fairies exist…wait, don’t go! They’re high-tech fairies! They have gadgets and guns! He kidnaps one and holds it for ransom, but then the fairies stop time, and…yes, I DID past the office drug test. Stop asking!”

But the book is better than its synopsis, too. There’s storytelling ideas at work here that I haven’t ever seen attempted before or since (even in the book’s own sequels). Want another book like Artemis Fowl? Go to your local bookstore, find the fiction section, look up “Colfer” under the Cs, and purchase Artemis Fowl again. Now you’ve got two copies, and that’s the best you’re going to do. Sorry.

The plot is essentially a kidnap and ransom story, but Colfer’s masterstroke is in the details: particularly centering the story on its villain. Later books would turn Artemis into a good guy: they soon devolved into repetitive, uninteresting capers where Artemis and his fairy pals go gallivanting off to bust the Villain of the Week, and I got bored of them. In the first book, Artemis is genuinely sinister and unpleasant, and a great character. Hell for the company.

Here (as in many places), the book takes cues from Die Hard: that movie developed its villain to the point where he stole the show – you wanted to find out exactly how Hans Gruber would pull off this ridiculous heist, with all the odds stacked against him.

Colfer kicks it up a notch by pitting twelve year old Artemis against a supernatural police force who can do anything from make themselves invisible to removing memories. Of course, the fairy police are as bumbling and bureaucratic as Die Hard’s LAPD, sometimes almost comically incompetent. And they are bound by magical rules – if they enter a dwelling uninvited, the instantly lose their magical powers. And when you’re a guest in someone else’s house, you have to obey the host’s commands. This makes life interesting when the host decides you can’t leave.

The book becomes a fascinating conflict between an almost omniscient race of fairies…and a really smart, really evil kid. That adds to the rising drama: it’s genuinely unclear who will win at the end, and again we see the necessity of Artemis being a bad guy. Nobody would write a children’s book where the hero loses. But a villain…?

Artemis Fowl has flaws (some of which would metastazise like a cancer and kill the later books in the series), and often succeeds more on shock and awe tactics than amazing writing. Tip: read it very fast. That way you won’t have time to think about the finer details.

Details such as how the fairy cops are called the Lower Elements Police Recon, or LEPrecon (leprechaun!). That gets a laugh, but why do fairies use English words, when they’re explicitly described as having their own language? And how did “leprechaun” (a word dating back to the 17th century), come from “recon” (a military abbreviation of “reconaissance” that apparently dates back to the 1940s, if Ngram viewer is correct)?

Artemis apparently possesses magical powers of his own, such as when he uses a household magnet to unscrew a screw (magnetic torque can’t operate on a uniform substance such as a metal screw). This is also one of those books where a character translates a text in an ancient language, and it comes out in perfect rhyming English couplets. Sometimes Colfer just loses track of his own rules. A “bio bomb” is described, which explodes and turns living tissue into “a cloud of radioactive molecules”…but a group of characters journey into the fallout zone of one expecting to find bodies.

The Artemis Fowl books never gained the mass fame of the Harry Potter series. In my opinion, they’re collectively not as good. Harry Potter had an arc that continued from book to book, but Artemis Fowl didn’t even feel like it needed a sequel. The premise was fully explored, and afterwards there was nowhere left to go. The kid-friendly trappings held it back a bit: it feels like a story for grown-ups at its core, and it would have been improved by a bit more of an edge. Marketed wrong, promoted wrong, and developed wrongly by its own author, in isolation Artemis Fowl is an extremely good piece of work.

No Comments »

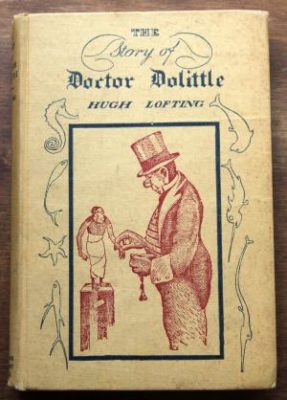

Action, adventure, and uncomfortable ethnic stereotypes; The Story of Dr Dolittle has everything you could ever want in an early 20th century children’s book.

The book (and the series that follows it) features a scatterbrained doctor with the ability to talk to animals. The first two or so Dolittle books follow a strict format: John Dolittle goes adventuring, gets into trouble, animals rescue him in a funny or interesting way, all of this happens again about ten or fifteen times, the end. Hugh Lofting soon grew in sophistication as a writer, the later books tend towards singular stories with allegorical themes. These often focus entirely on animals, dropping Dolittle out of the picture entirely.

There’s surprising philosophical acuity to Dr Dolittle. Wittgenstein said “If a lion could speak, we could not understand him”, and Hugh Lofting plays with this idea: humanity is cut off from the animal world by language, and this represents our failing. Who says animals don’t talk? Have you heard how incessantly birds chatter? How much dogs bark? Animals are always talking, constantly sharing thoughts and ideas, and we aren’t listening. The Dolittle books can be didactic on this subjects, and the latter ones feel written by a temporally displaced PETA activist. Often they verge on expressing outright contempt for humanity.

We have a good guess as to where Lofting’s antipathy comes from.

The Dr Dolittle tales started out as letters, scribbled and sent home from the trenches, and the author’s wartime experiences hang over the Dolittle tales like a flag’s shadow: never touching the story, but always present. The Great War was a bad one, industrial revolution alchemizing the battlefield, and a generation of young men witnessed entrails slithering out of bullet and bayonet wounds, faces melted by mustard gas, and mobile hospitals where the shrieking never stopped and the ground stank for weeks after. In the midst of this, Lofting was struck by the gallantry of horses and mules, and was embarrassed at how little his fellow men could do for them. He created John Dolittle in retribution, a physician who could give them the medical attention they seldom received in real life.

Other writers for children – JRR Tolkien, AA Milne, CS Lewis – also served in the war, and were influenced in various ways. Tolkien rejected modernity. Milne tried to wallpaper over reality with fantasy and whimsy (is it disturbing that he named his son “Christopher Robin”?). CS Lewis retreated into spiritual nihilism: nothing matters because the world shall soon dissolve like snow; the sun forbear to shine.

Lofting became a misanthrope. He believed, at the end, that humanity was a mistake, that we do not deserve our place on the planet. As the Dr Dolittle books progress, they get blacker and angrier, increasingly given to polemics about the irredeemable evil of humanity. I never finished Dr Dolittle and the Secret Lake, it was wearisome and depressing. Lofting’s disgust becomes a suffocating hand, strangling life from his stories. But that’s many decades away. The Story of Dr Dolittle is fun, with barely a hint of future despair.

As with most good children’s stories, it invites you to take it seriously and ask questions about its world. For example, when does the story take place? The opening passage says that it happened “when our grandfathers were little children”, and the parrot Polynesia (who claims to be either one hundred and eighty one or one hundred and eighty two years old) describes seeing King Charles II hiding behind an oak tree, an event that happened in 1651.

This dates the book to no later than 1832, and makes aspects of it anachronistic – John Dolittle wouldn’t be able to vaccinate the sick monkeys, for example. There’s clues that the book might be set even earlier – the doctor is menaced by Barbary pirates, who had been pacified for over fifteen years by that time. But that would throw still more story elements out of date: such as an Italian organ grinder with a monkey (which is an artifact from the 19th century). The monkey in question later tells stories passed down by his ancestors about “…lizards, as long as a train, that wandered over the mountains in those times, nibbling from the tree-tops.” This was interesting. People in 1920 knew about dinosaurs, but didn’t know they lived in a different time to primates.

Something should be said about the story’s…uh, racial complexities. In short, John Dolittle ends up at the mercy of an African tribe, whose prince, Bumpo, wishes to become a white man. In return for freedom, the ever-resourceful John Dolittle uses medicine to bleach the prince’s face.

Make of that what you want. My two krugerrand: Bumpo is a strange man and his desires are clearly depicted as abnormal in the story (one character calls it a “silly business”, and another states that he looked better as a black man). And given that skin-lightening is now an industry worth tens of billions of dollars (with over 70% of Nigerians using some sort of skin-lightening product, according to WHO), a desire for paler skin clearly isn’t an idea that sprung wholesale out of Hugh Lofting’s evil, racist brain.

The book’s imaginative, but sometimes I wish it went a little further. The episodic “adventure / problem / escape” format can get repetitive, and there’s fascinating possibilities left unexplored. Long chunks of the book involve the doctor trying to bring a rare beast back from Africa – a “pushmi-pullyu”, which has a head at each end of its body (there’s an argument that Dr Dolittle inspired Nickelodeon’s Catdog). The Doctor plans on exhibiting the animal as a sideshow, thus saving himself from financial ruin. One wants to yell at him “You can talk to animals! There are thousands and thousands of ways you could become rich! Use mice to steal the crown jewels! Use paper wasps make casts of the locks to the Bank of England! Use dolphins to patrol the sea floor and find sunken treasure!” If the Doctor wanted to, he’d be running the British Commonwealth within twenty years.

But those goals would be amoral. John Dolittle is so saintly he’s boring, and I wish he had a Moriarty: someone who shares his zoolinguistic powers but uses them for evil, not good.

The Dr Dolittle series enjoyed a good run, but it doesn’t seem to be remembered alongside Winnie the Pooh and Alice in Wonderland. Do the racial elements make the books unsalvagable? That would be a shame. In 1998 it was loosely adapted as big budget Hollywood comedy starring Eddie Murphy, and again as an accidental comedy starring Robert Downey Jr. No doubt it’s being reprinted inside plague bags lest innocent bystanders be infected with racism or something. Buy it however you can find it.

No Comments »