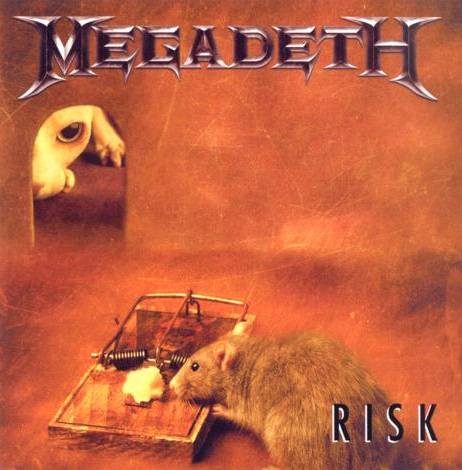

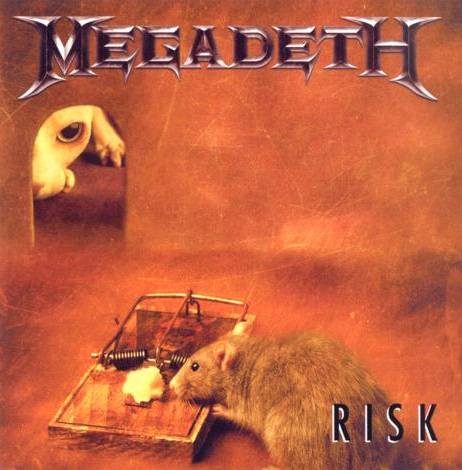

Did you ever think that the mouse hole on the cover of Megadeth’s Risk looks like a eagle’s head? You might need to step back to see it. The cat’s left paw is the beak.

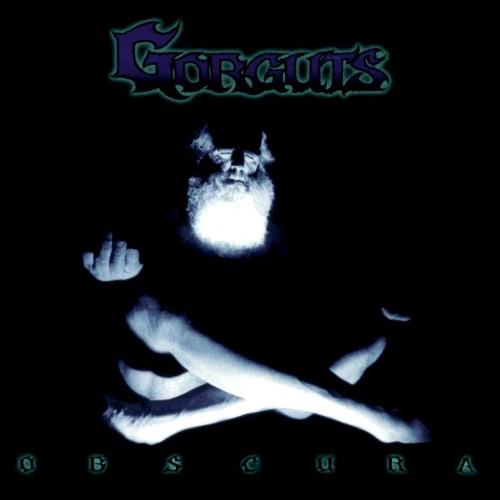

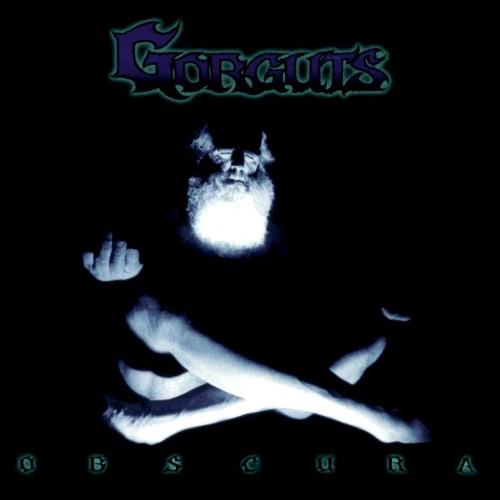

Gorguts’ Obscura is even worse. My eyes keep processing the man’s head as a pig’s head.

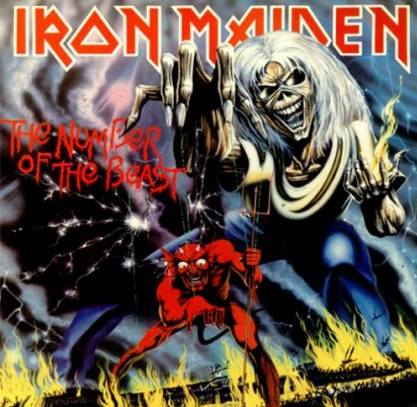

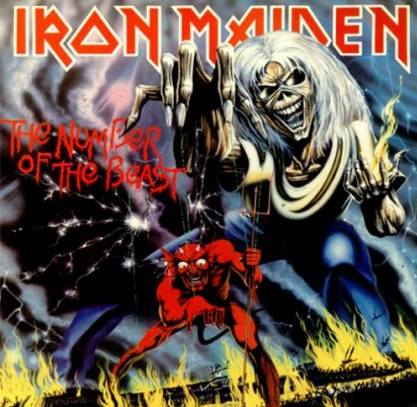

I hate the bolts of lightning on Iron Maiden’s The Number of the Beast. They look like cracked plastic, and when I see it my first thought is always “my CD got stepped on.”

Ride the Sky’s New Protection is meant to depict an angel emerging from a cocoon, except it looks more like an angel who has, in scientific parlance, had a bat. The glistening gelid strands on his torso, his relaxed posture and expression…I can’t unsee it.

No Comments »

No Comments »

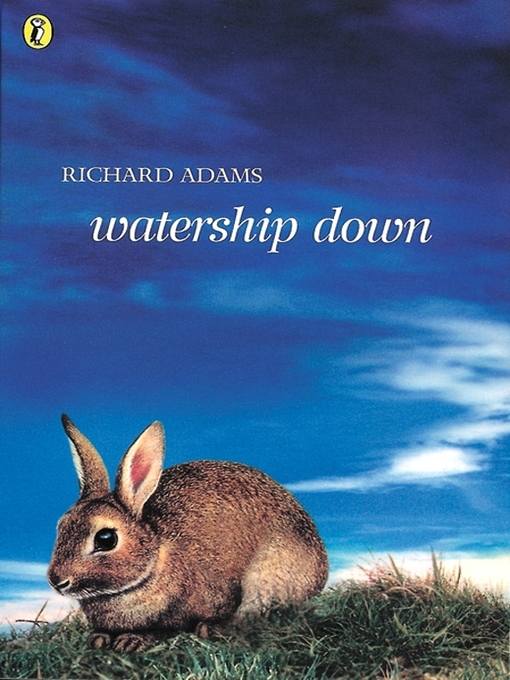

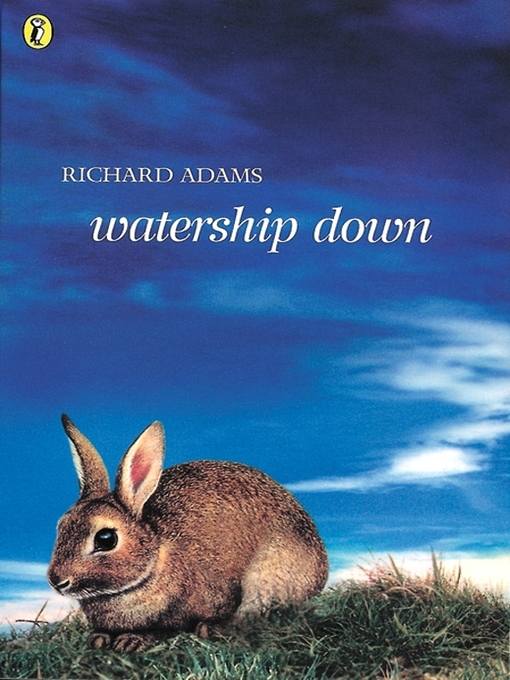

This book humbles you, and makes you realise how powerful stories can be. It’s about rabbits.

This book humbles you, and makes you realise how powerful stories can be. It’s about rabbits.

It’s been said that carnivores evolved binocular vision – both eyes pointing forward – because it’s better for hunting, while herbivores have eyes on the sides of their heads to maximise their field of vision (there are exceptions, pandas have binocular vision, for example). Combine sideways eyes with disproportionate ears and fast legs and you have a rabbit, a creature with a thousand enemies. To be a rabbit is to live in fear. Your very design is a statement of your vulnerability.

It must be stressful to be a rabbit. Constant danger. Constant alertness. Attacks might come from any quadrant and any direction – the sky, or the ground below. Your weapons are inadequate. Your only defence is vigilance. Fortunately, the fictional rabbits in this story have another defence: a precognitive runt called Fiver who one day has a vision of destruction falling on their warren.

Attempts to persuade the chief rabbit fail, and a handful of believers abandon the warren. What follows is an adventure in southern England, and then an attempt to start a new warren next to the aggressive and warlike Efrafans.

Adams makes us feel the terror and smallness of a rabbit’s existence. Human things like trains and bulldozers seem as monstrous as Greek titans. Cats seem as cruel to us as they do to the numerous small creatures in the story. There’s a scene where the heroes are helping some rabbits escape from a hutch and it feels like they’re storming Fort Knox. Reading Watership down is like watching an IMAX movie, every blade of grass magnified a hundred times on the screen.

The numerous scenes of lightness and comedy (such as the stories of the mythological rabbit El-ahrairah) are perfectly inserted into the story, and relieve the tension without breaking it. Characterisation is another strong point. Every real life rabbit has seemed boring indeed next to these ones. Nearly every real life human, too.

Some authors cheat and make their animals into humans (as in Pride of Baghdad). Other authors are conservative and leave their animals fully animal, which sounds laudable but is often boring in practice (I think Tarka the Otter was like that, but it’s been years since I’ve read it).

Richard Adams achieves a balance. The rabbits are anthropomorphalised enough so that we relate to them and understand their motives, but they are still animal enough to thrill the reader with their strangeness.

Despite their vulnerability, rabbits have proven to be astonishingly successful. A thousand enemies haven’t stopped them from devastating my country’s ecosystem. This book is equally successful, and far less harmful. It’s an amazing story that exalts the small, and makes holes dug in the ground seem like palaces.

No Comments »