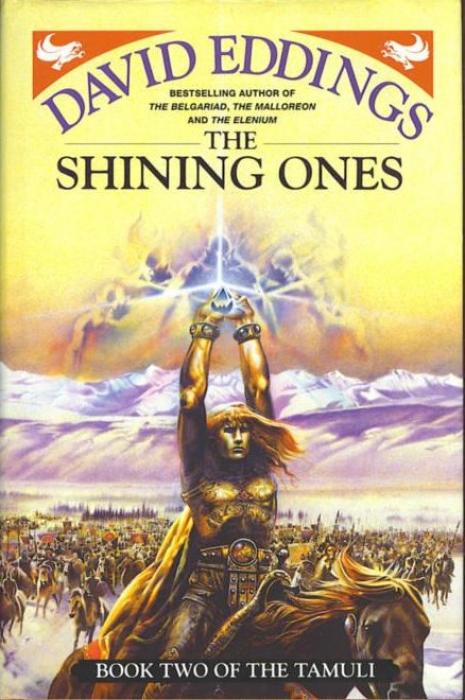

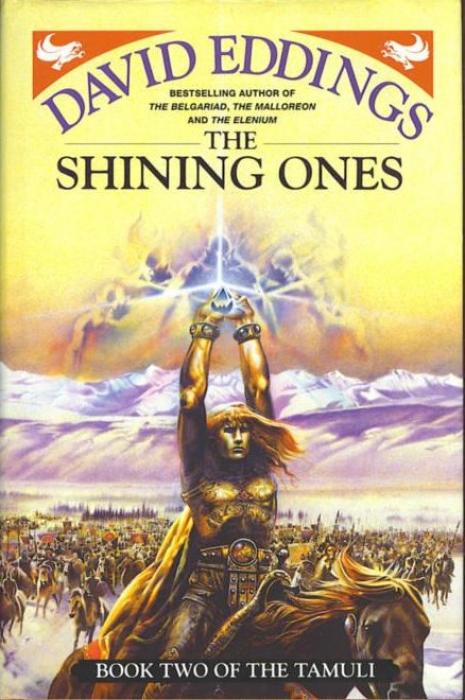

This is the most pointless and boring fantasy series that I’ve read BY FAR. Even if it possessed one small testicle and had podiatric contact with a single withered buttock it would have more balls and kick more ass than it does now, which is none and more none, respectively.

This is the most pointless and boring fantasy series that I’ve read BY FAR. Even if it possessed one small testicle and had podiatric contact with a single withered buttock it would have more balls and kick more ass than it does now, which is none and more none, respectively.

The Tamuli is a series of three books featuring the character Sparhawk, who appeared in a previous Eddings trilogy called The Elenium. The Elenium was a feeble fantasy series in its own right, lightly fingering the reader when he wants to be fistfucked, but it had good characters and snappy dialogue.

This has good characters and snappy dialogue, too, but the story is rotten and decrepit to the core. These books run about a thousand pages in paperback, and I am unable to care about anyone or anything in them. There are journeys to strange lands and invocations of mighty magic, and they bore me. The Tamuli shows us how to do less with more – how write a book about gods and wizards and the end of the world…and make the reader yawn. Remarkable.

The book suffers from the same problem that torpedoed Brian Jacques Redwall series: villains that aren’t a challenge to the protagonist. Eleizer Yudkowski once advised fanfiction writers “You can’t make Frodo a Jedi unless you give Sauron the Death Star.” In this book, Sauron is a Jedi and Frodo has the Death Star. The heroes are always ten steps ahead of the villains. Battles are easy squash matches. Gods are on Sparhawk’s side. Spawhawk himself has the powers of a god. What gives? Miss Marple is at greater risk in her investigations than these guys.

Mostly, The Tamuli is a series of tedious happenings, and an overburdened edifice of a plot that’s sagging inward under its own weight. It’s never clear how much significance to assign to specific plot points. You don’t know whether they’re vital clues or filler…and there’s filler in abundance.

We get scenes about the wacky love life of Bevier, or the anthropology of the Tamul empire, and David Eddings’ fem-dom fetish. There’s a female warrior called Mirtai, and Eddings’ frequently reminds us of how powerful and strong she is (and how she’s a match for any man) in rapturous fantasies normally reserved for paid membersites with “goddess” in the URL. Enough, man. Getting creepy here.

Even more irritating is that he cuts interesting things out of the book. In The Hidden City it’s mentioned in passing that a huge battle has been won against Cyrgai troops. I might have been interested in that. Instead, I get it second hand. I’m reminded of when I was a child, and listened to an audiobook of CS Lewis’s The Horse and His Boy – with the climactic battle scene cut out to save space on the tape.

There’s lots of happenings and lots of detail in these books, and it all seems like the buzzing of flies. The Tamuli can be compared to a plate of mashed potato. Lots of crags and valleys and hills. Lots of interesting things if you’re a potato aficiando. For the rest of us, it is a lump of mashed tuber.

No Comments »

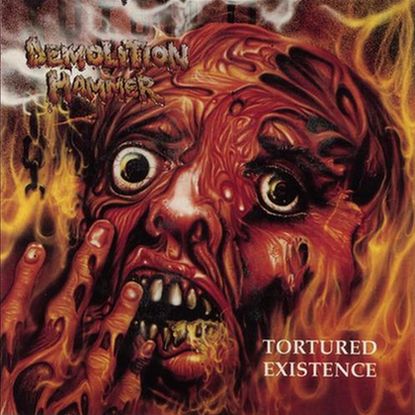

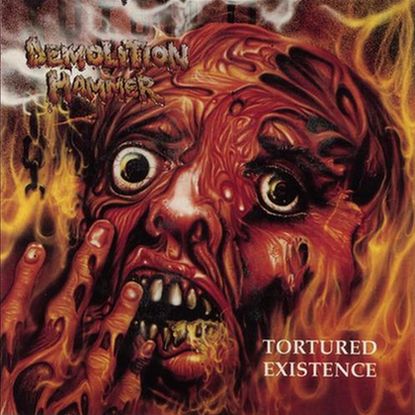

Metal has two taxonomies: the sort with ballads, and the sort without. Demolition Hammer is part of the second sort. There’s not a lot of music here to show your girlfriend, although if the timing’s right she might relate to “Infectious Hospital Waste.”

Metal has two taxonomies: the sort with ballads, and the sort without. Demolition Hammer is part of the second sort. There’s not a lot of music here to show your girlfriend, although if the timing’s right she might relate to “Infectious Hospital Waste.”

Tortured Existence is the first of Demolition Hammer’s three albums. The third sounds like Pantera/Prong mixed with the shitty sixth Ministry album. The second is a thrash metal coat of many colours, influenced by Slayer, Sepultura, Dark Angel, and others. The first album, however, has tunnel vision for a single style, New York brand thrash. Demolition Hammer don’t do anything original, but they sound inspired and energetic.

The riffs are aggressive and unrelenting, similar to Stormtroopers of Death and Nuclear Assault and various other bands from The City That Never Sleeps (Because You’re Playing Metal Too Loud). The production has an odd character. The guitars are loud and guttural, with the mids EQ’d away, giving them a crushing but not very heavy aesthetic – listen, and judge for yourself. Tortured Existence feels like being strangled by a warm, soft paw.

The songs all sound similar, but to the attuned ear there’s variation. “44 Calibre Brain Surgery” is the craziest track, “Crippling Velocity” is the fastest, and “Infectious Hospital Waste” is the catchiest, with most of the other songs walking the territory in between. The songs stick to a formula of punishing riffs interspersed with lead breaks interspersed with barked vocals interspersed with gang shouts. And then, just as this album’s one trick is getting dull, it all ends.

Derek Sykes and James Reilly are a tight rhythm team. The deceased Vinny Daze is an able drummer, although unworthy of the embarrassing levels of praise heaped upon him by some members of the online metal community. I think he suffers from Dead Rockstar Syndrome, where talented, above-averaged musicians like Cliff Burton and Randy Rhoads get hagiographed into musical geniuses. Steve Reynolds barks out lyrics about social, political, and medical aberrations with a distinct Australian-sounding accent.

Tortured Existence was released in a year starting with “199-“, so the timing could have been better for this band. Rather than riding the upward surge of thrash, they had their halcyon days right when the genre was shutting down. They were consigned to cult band status when they had the talent and potential to be much more. They soldiered it out for two more albums (the last one being a horrible attempt at ripping off Pantera), then broke up. There was a cash-cow anthology release from Century Media in 2008 (publically disowned by Derek Sykes), and that’s it for these guys.

For now, though, the Demolition Hammer crashes down. It’s a solid release that deserves its cult status. You could never call it a game changer, but some games aren’t meant to be changed.

No Comments »

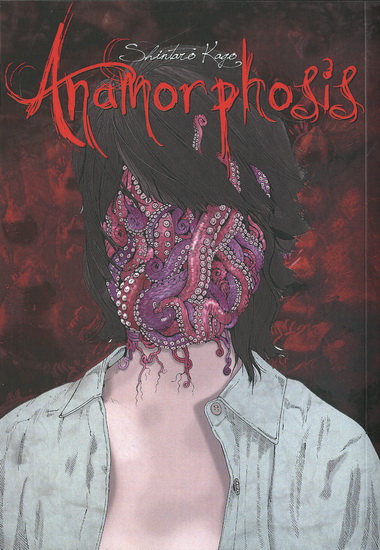

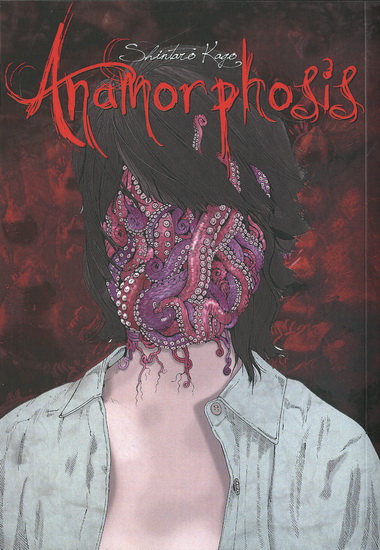

They used to ask the foul-mouthed “do you kiss your mother with those lips?” For Japanese mangaka Shintaro Kago, the equivalent is “do you think about your mother with that brain?” This guy has made a career of being fucked in the head, and the Shintaro Kago Mental Pathology Express keeps on rolling down the tracks with Anamorphosis, yet another collection of the bizarre and the grotesque.

They used to ask the foul-mouthed “do you kiss your mother with those lips?” For Japanese mangaka Shintaro Kago, the equivalent is “do you think about your mother with that brain?” This guy has made a career of being fucked in the head, and the Shintaro Kago Mental Pathology Express keeps on rolling down the tracks with Anamorphosis, yet another collection of the bizarre and the grotesque.

The centerpiece is a long-winded parody of House on Haunted Hill. A group of people must stay on a haunted movie set for 48 to win a bet. Not his most satisfying work, but quite enjoyable if you like black comedy and macabre slapstick. Unusually elaborate for Kago, too. It’s not every day he writes something that needs a dramatis personae. It also has a fair few kaiju/monster movie references, and the result is amusingly syncretic – as if Vincent Price and Godzilla had a baby together (in the world of Kago’s manga, such a thing is definitely possible.)

The rest of the volume contains a bunch of Kago one-shots. “Bishoujo Tantei Tengai Sagiri” is about a female detective who must solve a ludicrous murder. “Rainy Girl” stars a girl who attracts rain wherever she goes, and the complications this brings to her sex life. “A Small Present” returns to Kago’s much-loved theme of infant murder. “Hikikomori” is about students refusing to attend school – with nauseating results. Kago’s gross-out work gets all the press, but he’s a talented satirist, too. “Behind” uses a common real-life fear – doctors leaving surgical tools inside their patients – as its kick-off point, although obviously he takes it to strange and unwholesome conclusions.

“Previous Life” is rather clever. A girl is possessed by a snake, and a spiritualist discovers it’s because one of her ancestors killed a lot of snakes (karma, etc). Fortunately, the spiritualist is able to go back in time and stop the snake killer in his tracks. The girl’s sister sees a business opportunity, and manipulates other peoples’ pasts to help them succeed in the present. She has an swimmer’s ancestor kill lots of fish to improve her time in the Olympics. She has a mangaka’s ancestor kill lots of mangaka to improve his drawing skills (there’s a funny panel with Tezuka et all getting blasted with a shotgun). She also has her own ancestor kill buxom women so that she’ll have big tits (her father: “I wanted her to stay flat.”).

“Salesman” is about a girl who approaches the forlorn, and, rather than save them, helps them commit suicide in the most efficient way possible. “Changes” is a freaky gross-out story, archetypically Kago. “Weightlessness” is the volume’s finest moment. Such an unprepossessing little story, but the reveal at the end really took me by surprise.

The nice thing about Kago is that his comics, offensive subject matter or no, are always accessible and user-friendly. There’s none of the abstract Boschian ramblings of Usamaru Furuya’s Garden or the dizzying web of imagery that’s Suehiro Maruo’s Paranoia Star or any of the other excesses of most products described as extreme manga. Only Junji Ito beats him in mainstream appeal. With the title story Kago diverts a bit from his normal path, and it’s no coincidence that “Anamorphosis” is the only part that drags. Kago’s at his best when he’s on a roll – hitting you with shock after shock, not letting you breathe. The title story requires him to devote page time to subplots and characters, and you can feel some of his usual manic energy ebbing away.

But never mind. Kago’s a consistently entertaining mangaka, and Anamorphosis is another superior product from him. Step right up, and join the Kago Kult.

No Comments »

This is the most pointless and boring fantasy series that I’ve read BY FAR. Even if it possessed one small testicle and had podiatric contact with a single withered buttock it would have more balls and kick more ass than it does now, which is none and more none, respectively.

This is the most pointless and boring fantasy series that I’ve read BY FAR. Even if it possessed one small testicle and had podiatric contact with a single withered buttock it would have more balls and kick more ass than it does now, which is none and more none, respectively.