When you read early erotic novels (1748’s Fanny Hill, 1747’s Les Bijoux indiscrets, 1787’s Justine, etc), something sticks out. No, not that. Don’t be disgusting.

I’m talking about the authors: Cleland, Diderot, Sade, etc. They’re all men. Female-written erotic work in the Western canon literally crosses from Sappho’s poetry (~570 BC) to Pauline Réage’s Story of O (1957) in one step, with nobody in the intervening 2,527 years. Early erotica authors were literally all male.

Or were they? It’s possible (though unprovable) that one of the shadier early manuscripts was written by a woman, and either published anonymously or under a man’s name. Note that that the two prominent female erotica authors of the postmodern era – Réage and Anaïs Nin – both took active steps to conceal their identities. Réage was a pen name. Nin’s stories in Delta of Venus (which were written in the early 1940s and published posthumously in 1977) were intended for a private collection.

“Death is a mystery, and burial is a secret,” Stephen King wrote in one of his books. So is sex, at least where women are concerned. We accept with a shudder that they have sex (that’s where babies come from), but writing or reading about sex? That’s just too weird. Men are beasts and can’t help themselves, but why would a lady write about something that should be hidden?

Well, the hiddenness makes it attractive. The box you most want to look inside is the one you’re told to leave alone. It’s the censor’s paradox: people want forbidden fruit.

The increasingly explicit content of the mid 20th century ruined erotica, in books as well as film. It’s rather like Johnny Rotten’s observation that you demystify the swastika by wearing one: if everyone dressed in Nazi regalia, it wouldn’t trigger the cultural acceptance of fascist ideas: it might actually do the reverse. Could anyone feel awe at the sight of a sonnenrad, after seeing the lamest dork in the neighborhood wear one?

Anaïs Nin’s early writing actually has more shock value than modern porn; you can see her hands bleeding as she pulls walls down.

As I’ve said, we were never meant to read Delta of Venus. This adds the reader’s unintended voyeurism to sins on the page, which are legion: incest, buggery, rape, bestiality, and pedophilia. Nin writes about all of this with an praeternatural lack of judgment. She just documents human iniquity on the page, the way a camera obscura might.

It’s certainly diverse. One wonders what Nin’s collector (probably a heterosexual man) got out of stories like “The Boarding School” (“The experienced boys penetrated his anus to satisfy their desire, while the less experienced used friction between the legs of the boy, whose skin was as tender as a woman’s. They spat on their hands and rubbed saliva over their penises. The blond boy screamed and kicked and wept, but they all held him and used him until they were satiated.”). Sometimes the tales are gruesome and excessive. “Mathilde” and “The Ring” feature genital mutilation. Horrible stuff. You shouldn’t want to read it. I forbid that you read this book. Please don’t open the box.

It seems to me that erotic writing has gentrified itself. It now possesses rules about what subjects are okay, what subjects are off-limits, trigger warnings, and so forth. Some AO3 stories have lists of tags and disclaimers that are nearly as long as the stories themsevles. By contrast, Delta of Venus offers a look back at a weirder, wilder time: where erotica was so far from the pale it was almost in the black.

Nin, like Tolkien, was rediscovered in the 70s. She cuts a confusing figure: it’s hard to know what to make of her. She was of Hispanic descent, yet her settings of Brazil and Peru seldom rise above exoticism (her descriptions of Paris in “Marcel” are far more vivid). She rejected the Catholicism of her youth, yet it hangs across her writing like the Shroud of Turin (“The Boarding School”, for example, gets most of its punch from the emotional repression of its setting).

She’s hard to claim as a feminist figurehead. She lived under the shadow of men all her life: Henry Miller, DH Lawrence, her father, and the anonymous “collector” who made all of this possible. The stories are all written for male consumption, although with shards of her personality poking through the pornographic narrative like iceberg-tips. She stands in two epochs: old-fashioned yet modern. This make her captivating: she can’t be captured for some political cause.

“I will always be the virgin-prostitute, the perverse angel, the two-faced sinister and saintly woman.”

Anais Nin, Henry & June

Even her descriptions of sex embody this contrast, with high romantic verbiage clashing with gutter crudeness.

“For the first time, the hunger that had been on the surface of her skin like an irritation, retreated into a deeper part of her body. It retreated and accumulated, and it became a core of fire that waited to be exploded by his time and his rhythm. His touching was like a dance in which the bodies turned and deformed themselves into new shapes, new arrangements, new designs. Now they were cupped like twins, spoon-fashion, his penis against her ass, her breasts undulating like waves under his hands, painfully awake, aware, sensitive. Now he was crouching over her prone body like some great lion, as she placed her two fists under her ass to raise herself to his penis. He entered her for the first time and filled her as none other had, touching the very depths of the womb.”

Artists and Models

The stories are mostly fast and short, thrashed out quickly, establishing a scenario that swiftly builds to an explosive climax (or climaxes). None take more than a few minutes to read. Nin was supposedly paid a dollar a page for this stuff: one admires her restraint in using so few paragraph breaks.

And while the stories seem bold and incredibly revealing, they’re nothing of the sort. Nin wrote this stuff for money. She was pushed at every turn by the “collector” to focus more on sex, more on body parts, more on the beast with two backs. Her natural inclination toward poetry was throttled. The introduction contains a letter, written by Nin to the Collector. It’s basically history’s first “men only want one thing, and it’s disgusting”.

Dear Collector: We hate you. Sex loses all its power and magic when it becomes explicit, mechanical, overdone, when it becomes a mechanistic obsession. It becomes a bore. You have taught us more than anyone I know how wrong it is not to mix it with emotion, hunger, desire, lust, whims, caprices, personal ties, deeper relationships that change its color, flavor, rhythms, intensities. You do not know what you are missing by your microscopic examination of sexual activity to the exclusion of aspects which are the fuel that ignites it. Intellectual, imaginative, romantic, emotional. This is what gives sex its surprising textures, its subtle transformations, its aphrodisiac elements. You are shrinking your world of sensations. You are withering it, starving it, draining its blood. “If you nourished your sexual life with all the excitements and adventures which love injects into sensuality, you would be the most potent man in the world.

introduction

Delta of Venus is well-written, but its stories often have a note of cynicism, or contempt. “The Hungarian Adventurer” describes a man of incredible attractiveness, charm, and virility (perhaps how the Collector liked to imagine himself?) before turning him into a bloated, aging pig, abandoned by his children. “Lilith” involves a woman trying to spice up a marriage with Spanish fly. The ending is such a thudding anticlimax that I think this must have been the intended effect.

These little rebellions against form are as fascinating as the form itself. Like Nin, the book is complex, with many layers.

“There is a perfection in everything that cannot be owned,” he said. “I see it in fragments of cut marble, I see it in worn pieces of wood. There is a perfection in a woman’s body that can never be possessed, known completely, even in intercourse.”

Marcel

By her own standards, Nin was perfect. Worn, broken, weird; selling prose for a dollar a page.

Yet she could not be possessed.

No Comments »

What did they think of “Talk Talk” in 1966? In 2023 it uncoils from your speakers like a cobra: alive and evil and glaring with death. It’s just 1:56 in length – short, even for the time. The tempo is punishing. The instrumentation is just lunges and stabs of fuzz; flames leaping from a barely-existent structure, as though the song’s burning down while still half-unwritten.

The lyrics are fragments. Ugly, mean thoughts, articulated with the stumbling self-seriousness of a teenager who’s drunk for the first time. “My social life’s a dud! My name is really mud!” Far from poetry…but people have thoughts like that. I used to. Sometimes eloquent phrasing doesn’t capture stupid, sullen emotions, “Talk Talk” may have been the first song they’d heard that truly sounded like the inside of their own mind.

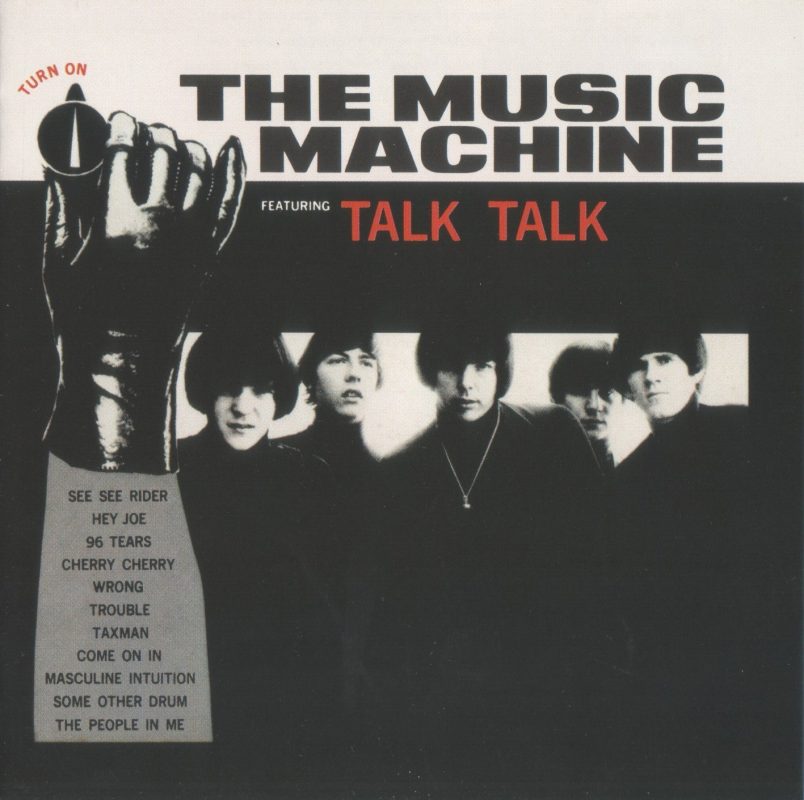

The band was a five-piece called The Music Machine. One year earlier, they’d been playing folk rock.

They were fronted by Sean Bonniwell, a restless self-reinventor who never found a home. “Talk Talk”‘s success (#15 on the Billboard charts in 1966) proved a fluke. They had no followup hit. They were driven first aground and then apart by royalty fights, label disputes, and internal discord.

Bonniwell tried to regroup, but the window he’d exploited was now gone and his moment had passed. The Music Machine’s legacy is 1:56 of brutal noise and an unfulfilled promise. From the outside looking in, it was as though they’d come from nowhere and then gone back into nowhere. They did not become a Great Band.

But in a weird way, that helps me appreciate Music Machine more. There’s a long list of “classic” Rolling Stone approved acts (The Eagles, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Queen) that I either can’t appreciate or appreciate in an academic thinking-things-through way. Part of it is their critical reception: they’re so adored and revered that it triggers suspicion in me. And it distances me from the music, I feel like I’m listening to it from across a GREAT BAND cordon line. The immediacy is gone.

Rock music was never supposed to be a canon, or an establishment. It was supposed to shake your bones. So I enjoy listening to bands like The Music Machine, that doesn’t have a Rolling Stone-appointed crown weighing it down.

If The Music Machine is remembered, it’s for either their heaviness, their earlyness, their subtle influence on other bands, or their rapid collapse. The entire band left soon after their first LP, aside from frontman Sean Bonniwell. He changed the band’s name, changed their style, and then left the music business altogether. It was as though the Music Machine had packed a thirty-year career into one minute and fifty-six seconds.

In other words, they were the Sex Pistols, ten years before. Which brings up the p-word.

Music journalism as we know it barely existed in the mid sixties: as a result, some history is barely-written and misremembered. A lot of people seem to think that punk rock was a seventies phenomenon. That was actually the second wave of punk. The first wave happened ten years earlier, with US “garage rock” bands like The Sonics and MC5, as well as UK acts such as The Downliners Sect and the Kinks. This was raw, aggressive, cheap-sounding music, driven by jangling guitars, powerful drums, and farfisa organs. Much of it was retroactively classified as “punk” in the early 70s – the first recorded reference to the genre is in the March 22, 1970 issue of The Chicago Tribune.

Unlike the second wave of punk (conspiracy theories about “God Save The Queen”‘s UK #2 aside), garage rock actually got some singles to number one. “”(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” by the Stones and “96 Tears” by ? and the Mysterians both reached #1, among others. It’s disputable to what extent these songs are punk. The lines between a garage rock band and, say, The Troggs or The Beatles could be pretty blurry. And their 1960s mod and greaser fashions have left less of an impression in the popular memory than the edgier styles pushed by Malcolm Mclaren and Vivienne Westwood.

The Music Machine were among the heavier of the 60s garage rock set, but soon psychedelic rock and heavy metal left them behind in sonic firepower, and Bonniwell proved unable to keep the band on the charts on the strength of his songs.

He was a clever and inventive songwriter, pulling inspiration out of the air, but maybe not actually a good one. “Talk Talk” is sonically impressive but soon wears thin. “Trouble” and “Wrong” are the best songs, particularly “Trouble”, with its dense and rubby rhythms and melodic complexity. “Masculine Intuition” has a really awkward chorus that doesn’t fit the verse. And it’s too short to develop its ideas much: all of these songs are sonic mayflys, dying before they can progress or go anywhere.

The album was recorded quickly to capitalize on a hit single. Most of the tracks were laid down at RCA Studios at three in the morning (on a hand-built ten-track machine built by engineer Paul Buff) after the band had been touring for thirty days, back to back, which explains Bonniwell’s hoarse, ragged voice. A surprising amount of punk aesthetic comes from what is ultimately accident and circumstance. Only in the aftermath does anything seem planned.

The band’s limited stock of originals is padded with covers, which are sometimes great (“Hey Joe” rivals Jimi Hendrix’s version. Bonniwell would later lament that his label wouldn’t release it as a single), sometimes pointless (“Taxman”), sometimes really stupid (“See See Rider”). The cover of “96 Tears” is pretty ironic, as ? and the Mysterians also failed to follow up their one hit.

The Music Machine is a fascinating curio, but they were riven by image and identity conflicts that they never figured out. Were they art, or yeah-yeah-yeah teenage music? They were initially presented as mods, but Bonniwell soon got into transcendental meditation and eastern mysticism. There was little sense of musical history to the Machine. You couldn’t obviously pick out their influences, the way you could for the Beatles or the Stones. This made them seem fresh, but also a little disconnected in time, as though they were visiting aliens. There wasn’t an easy “story” you could apply to the band, which made it easy for music history to not give them a story at all.

No Comments »

Remember that part in Indiana Jones: The Title IX Violation where an Arab character twirls a scimitar around and Harrison Ford just casually shoots him dead? Wizards did that same gag four years earlier, and I want you to know that.

Three million years after a nuclear apocalypse, the Earth has mutated into a kind of high fantasy setting where people use magic (although there are mutants and caches of old weaponry waiting to be discovered). The queen of the fairies falls under a spell and gives birth to twins: the peace-loving Avatar and the malign Blackwolf, who discovers a trove of Nazi propaganda and decides to bring about a second Holocaust.

Wizards is sprawling, louche, animated movie, with no modern counterpart. It’s fundamentally and quintessential a movie by Raph Bakshi: whether this is a compliment, criticism, or neutral observation is your call.

It has little overriding style or aesthetic. It’s just the stuff Bakshi likes piled into one movie: namely British fantasy, a gritty countercultural vibe, big tits, and belabored social commentary. None of the ingredients really mix that well, which is kind of the point. Bakshi seems to be jarring your senses on purpose, playing off the flying sparks as jagged pieces of movie grind together.

This was his first (and most successful) flirtation with a Tolkien-style setting, and it works because it’s filtered through a lot of 70s decadence and doesn’t take itself seriously.

JRR Tolkien had become a mainstream craze in America during the hippie years (to his horror), with kids reading Lord of the Rings as an allegory for their times. The Shire was Woodstock, magic was weed/psychedelia, Gandalf was one of the wise elder “beats” (Ginsburg, Burroughs, Kerouac), Sauron was the Man, Saruman was a sellout to the Man, and so forth.

Bakshi was always more of a hippie observer than a hippie (1972’s Fritz the Cat is full of criticism for the excesses of the 60s counterculture), but he shared their fascination with Tolkien’s world, and the way its mythic setting cuts across cultural lines. Whether you’re an elderly Oxford don or a “turned on” flower power freak, everyone appreciates a well-kept garden, and everyone hates the bulldozer destroying it.

But when you combine hippie and Tolkien sensibilities, the result isn’t that coherent. The main thing you’ll notice about Wizards is how little it gels, and how awkwardly the parts fit together.

The art style is all over the place. Certain characters are drawn in a cheap TV cartoon style. Others (such as Blackwolf) are drawn in a more classicist Disney fashion. There are incredibly detailed backgrounds (and even rotoscoping), which really look odd next to the minimalism of the main cast.

I assume Bakshi wanted the film to look the way it does: like cels from wildly different films composited together. Illustrator Ian Miller and artist Mike Ploog contributed work, but they were deliberately kept separate during productiion. It’s heavily “influenced” by Vaughn Bode, as Bakshi would belatedly recognize. The movie occasionally feels crafted by a committee living on separate continents, communicating via carrier pidgeons.

Sure, the disjointedness make it a charming and personable movie. You come to love the incongruence, the way you enjoy the big, awkward stitching on handmade clothes.

But the tone never settles, and that’s a bigger problem. Wizards is a kids’ movie with bouncing boobs and swastikas. And the pacing is just bizarre. The first part of the movie is turgid: information and story lore gets dumped on the viewer with a tractor, and there’s ultimately little need for any of it.

It does get a lot better as it progresses. The battle scenes are thrilling, and Bakshi’s world is huge and vivid. He communicates sheer immensity better than most directors. You feel space and scale exploding out of the frame. The music is fantastic.

A tighter writing job would have helped focus the movie more, perhaps at risk of losing its unique aspects that make the film memorable. But there are many other directions Bakshi could have explored. What if he’d made a straight childrens’ film? Or doubled down on the political commentary?

As it is Wizards has themes, but no real time for them. The Nazi wizard angle is a fascinating one. The links between the real-life SS and such occultist movements as Ariosophism are fun to blather about (as many people have, ie Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke in his book Black Sun), but that aside…isn’t propaganda a kind of magic? The ability to control minds with images and words? Does it make more sense to regard Leni Riefenstahl as a filmmaker, or as a witch?

But this is pretty inconsequential in the film: Blackwolf inspires his soldiers with grainy old film clips of violence and war and Hitler speeches, and that’s it. Is that the essence of Nazism, according to Bakshi? Sound and fury? An angry, shouting man? Or is there an ideological component to fascism as well? It’s interesting to me that the world Wizards proposes (which is full of degenerate mutants, and an innately evil enemy who cannot be redeemed or saved) is probably more of a fascist one.

Matt Lakeman once wrote:

I have a friend who was a state-level legislator in the US for many years. Though ideologically libertarian, he ran as a Republican. He once told me that 80% of voters in America are actually libertarians. The problem was that 80% of voters are also actually Republicans. And Democrats. And progressives. And communists and fascists and monarchists and anarchists, and every other political ideology imaginable. They all want lower taxes but more social services, and to avoid wars but a strong foreign policy, and personal liberty but a safety camera on every street corner, etc. Thus, the key to my friend’s electability was to inspire their libertarian values while not triggering every other contradictory value they incoherently held.

This is basically Wizards. It’s trying to be everything for everyone, and scarily often, it succeeds. What do you get out of a movie this eclectic? Confusion? A desire for clarity? Or the sense of wandering in a delirious bazaar, overloaded with colors and noises and scents? For me it’s overwhelmingly the third feeling. It’s a flawed but impressive work, and at the top tranche of Bakshi’s work.

No Comments »