I saw this film for Christmas, the most wonderful time of the year.

One advantage of me being Australian (aside from the whole walking upside down thing, which gets old fast) is that I have an outsider’s view on American entertainment. For example, I don’t know who Kirk Cameron is. A sitcom actor, or something. When Saving Christmas came out and was hammered by critics, many reviews took the line of “haw haw! It’s Mike Seaver from Growing Pains!” I didn’t care about that stuff. I judged the film on its own demerits.

It’s terrible. Silver linings, though: we’re still celebrating Christmas in 2022, which means Kirk’s crusade to save the holiday was a success. I wonder how he did it?

Don’t be fooled by the action-packed cover: Saving Christmas is a vlog of Kirk Cameron sitting in front of a camera, gesturing with his simian hands, his ghastly chimp-like visage twisting with rancid condescension as he explains the meaning of Christmas to all of us dumb idiots. I have never felt so patronized by a stupid person. He has the energy of an uncle explaining that airplanes fly by flapping their wings.

He knows how to save a buck, I’ll give him that. The movie has two sets: “some dude’s house”, and “some dude’s car”. Occasionally he spices things up with “B-footage” that looks like it came from a stock footage site. This film cost literally dozens of dollars to make, and I hope it earned back every penny.

Is this even a movie? In 2017 it barely passed muster. In 2022 it more resembles a high-effort Youtube video by someone called “The Libtard Crusher” whose avatar is Trump throwing Fauci out of a helicopter. All it lacks is a crudely animated furry character who looks smug when he makes a point…well, it has Kirk Cameron, now that I think of it.

So what dubious message does Craptain Kirk have for us?

It’s not “Christmas is overcommercialized!” Kirk is all for commercialization. “Don’t buy into the complaint about materialism during Christmas. Sure, don’t max out your credit cards or use presents to buy friends, but remember, this is a celebration of the eternal God taking on a MATERIAL body. So, it’s right that our holiday is marked with material things.”

He argues – unconvincingly – that “secular” traditions (Christmas trees, nutcrackers, Santa Claus) are Biblically-based. Nutcrackers? They’re soldiers, and Herod had soldiers. Christmas trees? Jesus was crucified on a cross made of wood, which comes from trees. Baubles? They represent the fruit in the Garden of Eden. And so forth.

It’s a simple formula. Is $THING part of Christmas? Just Ctrl-F search for $THING in the Bible, and there you go. Anything you like can be a Biblically-approved Christmas tradition. “Like a computer wrote it” is a common criticism lobbed at movies that are formulaic or uninspired. Saving Christmas goes further: it’s the world’s first movie that could have been written by a one-line Bash script.

Winter? Well, God created the winter solstice. When he’s in a pinch, Cameron falls back to the “God made it” argument, which kind of makes the rest of the film unnecessary, because then everything is part of Christmas.

And this distresses me, because my family had a disgusting proctopaedophiliac Christmas tradition called “oobleklaart”. It’s a heinous sex act, banned in 31 countries and counting, involving a monkey, an unripe rambutan, a power drill, and…ugh…just thinking about it makes me shudder. Those poor gerbils…

Anyway, if Kirk is correct, oobleklaart is authentically part of Christmas, because the 27 separate items and ingredients necessary to perform it (we’ll ignore the plutonium-239, which is man-made) all come from God. Is this true? Is oobleklaart Christmas? Say it isn’t so, Kirk.

In general, I’m not on board with attempts to make Christianity hip and happening.

Firstly, none of these people would recognize “hip” if theirs was smashed by a sledgehammer. At the end there’s a rapped version of “Angels We Have Heard On High”, which is a risky move for a group of actors who have never heard a rap CD that didn’t have “CLEAN VERSION” on it. When they dance, they flail like electrified corpses.

Christianity should transcend cool. The Bible has a certain dignity to it. It’s not a trite or silly book. Trying to tie it up with a bunch of toys doesn’t even reach the level of sacrilige. It speaks to a cultish obsession with dopamine that’s as secular as it gets. “Don’t ask questions! Just consume product and then get excited for next product!” Christmas may survive commercialism. It may not survive Kirk Cameron.

No Comments »

Ambien is so-called because it gives you a morning (a.m.) that’s good (bien), Warfarin is thus-titled because it was developed by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, Lasix is accordingly-dubbed because it lasts six hours, Premarin is hencely-christened because it comes from the urine of pregnant mares, Adderall is consequently-designated because it relies on an organic compound found only in European snakes, Prozac is repercussionly-cognomenized because the chemist was into High School Musical. I started making these up.

So why is this website called Coagulopath?

Well, because of a small but extremely important fact about myself that I’ve never revealed to anyone. A secret, if you will. My time is now short, so I’ve decided to tell the world at last, in the form of a SHA-512 hash.

56bfdd67f46f62375b35cc9cce0a7b75

f2716bfdc98542709c4306c91e2084ee

4b6cb44951373ba5ef6f51b1b0875602

f710ee643fdde00f63aaebe4b7e79aaf

Now you know.

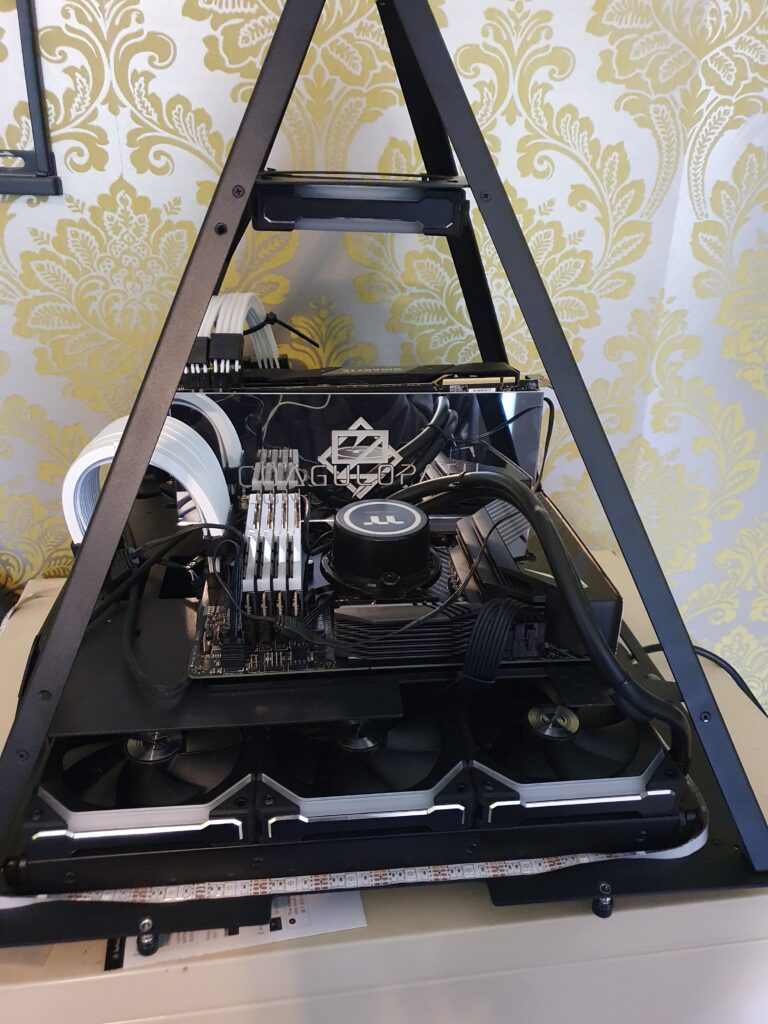

In 2021 I built a PC. I wanted it to be weird, with personal touches.

Parts list:

- AMD Ryzen 9 5900X 12-core processor

- MPG B550 Carbon Wifi motherboard

- Gskill 3600 32 GB DDR4 x 2 (64 GB total)

- RTX 2080 OC Super

- Lian Li 120MM Unifans x 5

- Thermaltake 360mm AIO

- Thermaltake Toughpower GF1 ARGB 850W Gold PSU

- Some other decorative parts

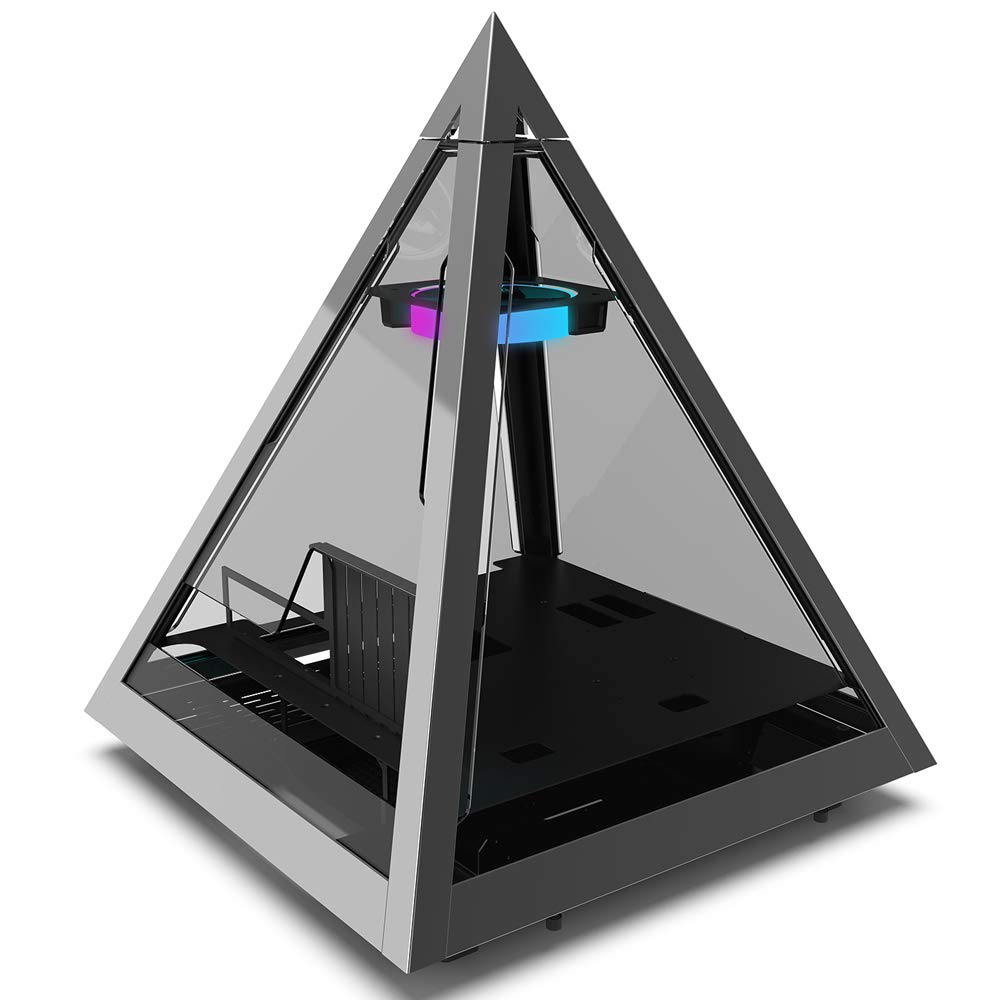

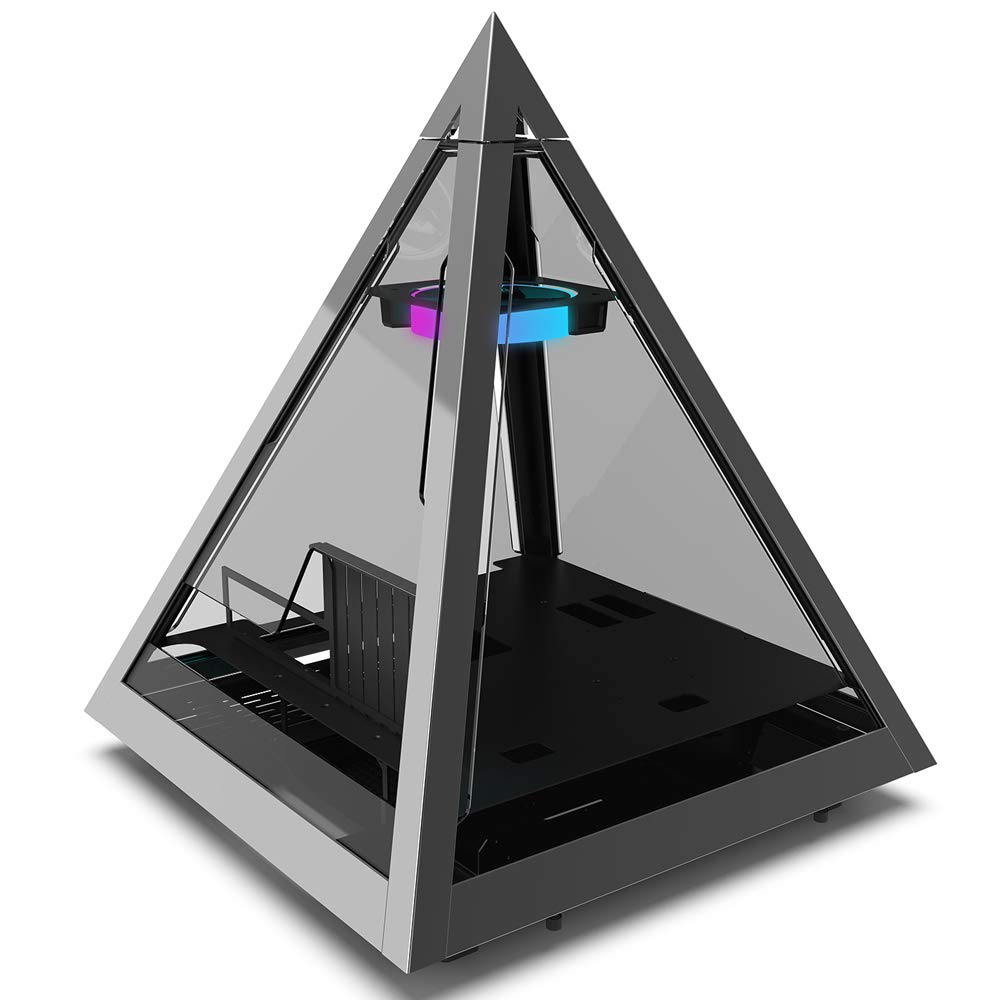

The case was the infamous AZZA CSAZ-804 :

This is the first mass-produced case with a pyramid shape. The AZZA Pyramid also comes in a a “V” edition (with darker paint and extra I/O options), a “Mini” edition (for mini-ITX builds), and a large edition. I now wish I’d gotten the large one. It has the same overall dimensions (589 mm x 490 mm x 490 mm) with differently-spaced cutouts for a RTX 30** series GPU.

Content advisory: many things about this build are just bad. Don’t copy this unless you are prepared to face terrible consequences.

Problems

- My GPU is sucking air through a glass panel

- Many of my installed games are bad, receiving 6/10 or lower from GameSpot

- My radiator pump is the highest point of the loop, causing air bubbles to gather in the pump (potentially shortening its lifespan, see here.)

- The case thermals are sucking of horse cock in general, with too much glass and not enough air

- I have Argus Monitor and Speedfan installed at the same time even though it says not to

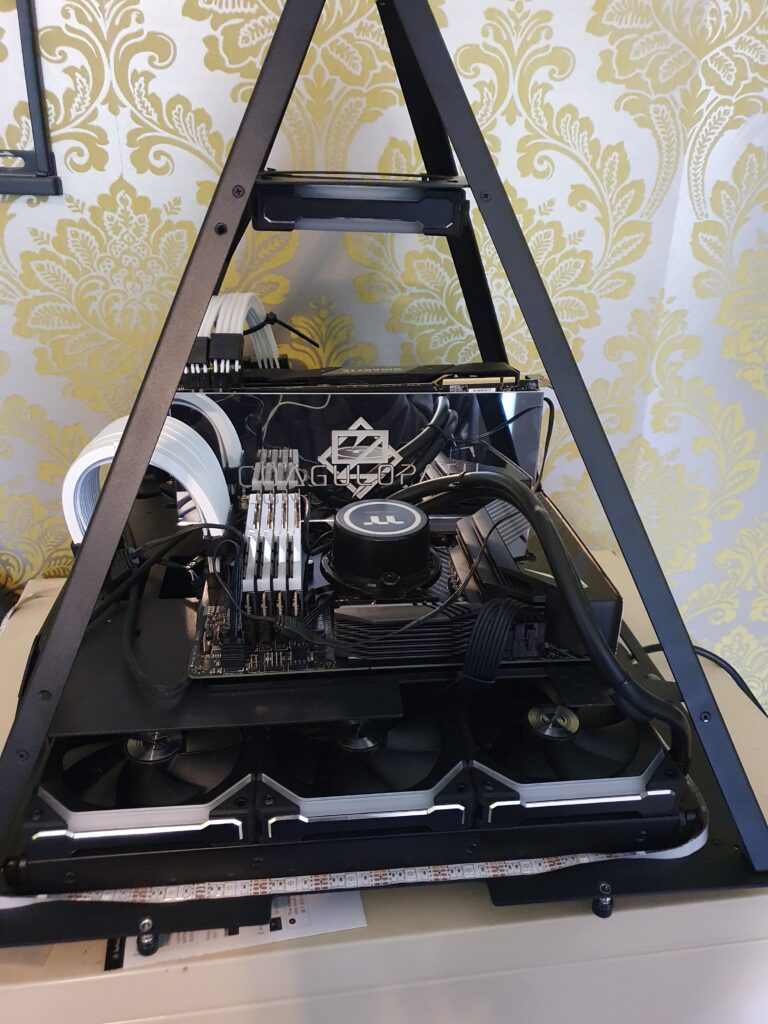

The PC is designed as a showpiece, not to perform well. That said, I got 240 FPS in the Apex Legends training range, and I was only about ~40C over ambient on a hot summer day: below thermal throttling for the Ryzen.

First, I unboxed the case, which was huge. The box seemed big enough to hold my entire life. It’s the heaviest case I’ve yet built in: with no parts it’s 14.1 kg / 31.1 lbs of cold-rolled steel and tempered glass. I don’t recommend dropping it on your foot.

The case has two levels. A “basement” where you put the PSU, radiator, hard drives, and cables, and an upper level that the motherboard mounts to.

It comes with a number of accessories: a riser cable for vertical GPU mountings, and a couple of docks for hard drives. I ended up using relatively few of these. I have no use for 2.5″/3.5″ HDDs and I mounted the GPU the standard way.

The “logical” way to set up this case would be to draw air from the bottom and expel it out the top. I used a 360 radiator, and because I wanted the fans to be visible, I set them in pull configuration. Usually, a gap of about 5cm is necessary for a case to ventilate (as found by Gamers’ Nexus Steve Burke). The AZZA satisfies this requirement.

The Unifans were great to work with. They connect in series by physically slotting together, like Lego bricks. The only disadvantage is that they use a proprietary Lian Li cable type and can’t connect to 4-pin / 5v RGB headers. I ended up with a mess of cables underneath the motherboard compartment.

At the top of the pyramid there’s a preinstalled AZZA-branded 120mm fan, which I replaced with another Unifan. I wonder why Azza didn’t include additional screwholes and brackets for 140mm and 200mm fans, which would allow you to put the fan lower down.

Why would you want to do this? Geometry. The 120mm fan has to be very close to the top of the pyramid, meaning the airflow misses the four sidecut vents. Additionally, there are possible static pressure problems, where the fan doesn’t just draw air from above the components (as is ideal) but also from the sides. If you did Schlieren photography of the case, I suspect you’d see a massive mushroom-cloud blob of heat just hanging over the motherboard. But again, this is a showcase. And a show case.

I used a lot of RGB peripherals, including RGB tape (which I ended up looping around the base of the pyramid), Lian Li Strimer Plus V2 24p + 8p*2 cables. To connect all of it I used one of these.

The engraved RGB backplate for my RTX 2080 OC Super came from JM Mods. It would have looked better without the mirror finish, but I didn’t think of that.

I also installed the Thermaltake power supply fan-side down, so the T logo is upside down. Triggered yet, libtard?

The cables under the motherboard tray looked pretty bad. They’re still a WIP.

Anyway, the Coagulopath PC is built. I have many more plans for it.

No Comments »

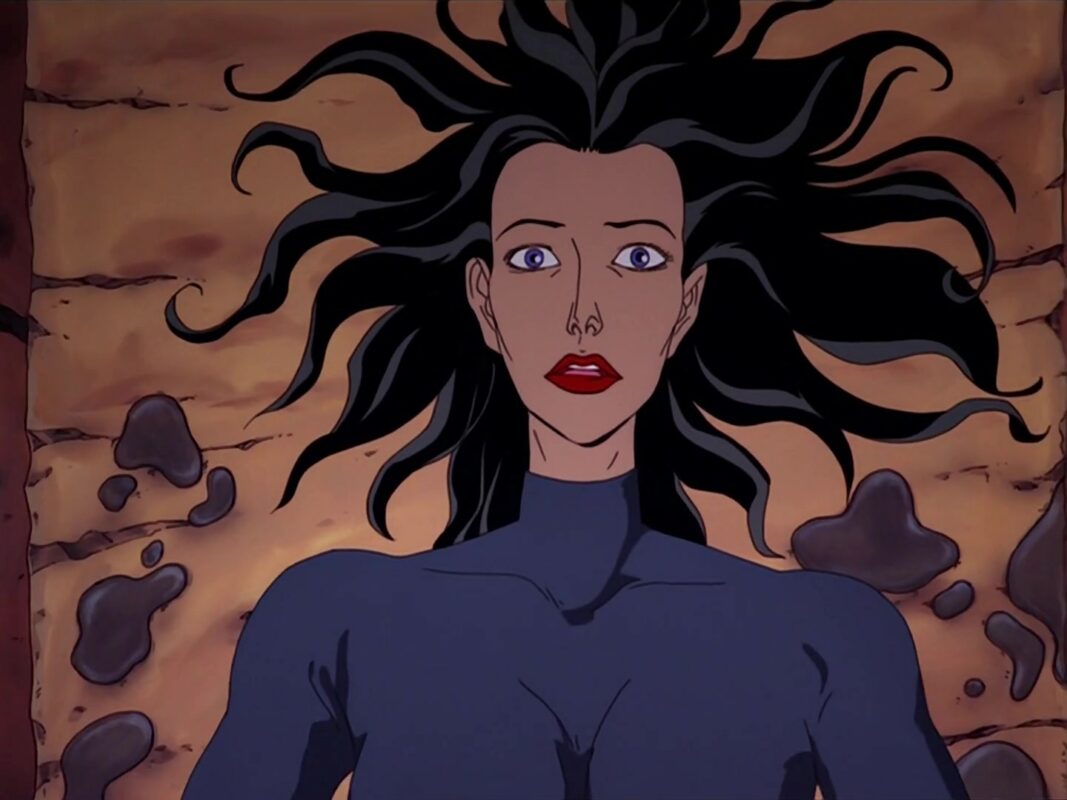

Aeon Flux S3E7, or “Chronophasia”, is one of the most confusing episodes ever put on TV for any series. You can literally feel your brain get further away from understanding it the more you subject yourself to it.

Tireless on your behalf, I have uncovered a few hard facts. For example, it’s the seventh episode of Aeon Flux’s third season, and I believe its title is “Chronophasia”.

How long does this go on? Always.

This episode triggers brain bleeds in fans.

Just have a glance at can anyone really explain chronophasia?, a twenty-five year old discussion where three Aeon Flux writers show up. And the result, after a quarter-century of argument?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Some have argued that “Chronophasia” has no meaning: that it’s either very badly written or a troll episode designed to enrage the kind of fan who obsesses over who killed Laura Palmer.

“So, in answer to the original poster, after all these years, with posts from people actually involved in the writing and creation of the short….No.

No, they can not tell you the meaning of it. No, they have not written an explanation of it. They don’t know why the baby was so powerful. They don’t know if the boy was there from the beginning. They don’t know what was in the vial at the end or why it aided in changing their reality. They have no idea why or how the mummified people died.

They have no idea what was created or why it was created(save to make a buck). It’s like watching a David Lynch film minus the few parts that make sense enough to string together a movie.

Absolutely nothing is to be gained on examination of this short other than that pieces have been placed in opposition and are blatantly left without any conclusion. It is not a reflection of life, metaphysics or science. It is a nothing. You can sleep easy now.

They divided by zero and the zero won.”

- ILXOR user iseewutudidthere

I don’t agree with this reading. “Chronophasia” is messy and unfocused, but there’s a dreamlike logic to it. And from a certain perspective, it does kind of make sense..

There’s just too much of it: the plot’s a 10-piece puzzle that has 11 or 12 pieces. There are a few different ways to assemble the puzzle so that it forms a complete picture, but there will always be pieces left over. We just have to be happy with that.

“There was never supposed to be one “right,” comprehensive interpretation of the episode (just as there is no “right” answer to whether or not there is an active virus or which — if any — of the scenarios represents “reality”). Ultimately dream logic prevails — tons of meaning but the solution never quite comes together in a consistent, comprehensive way. A number of possible dualistic alternatives are set up — waking vs. dreaming, madness vs. sanity, reality vs. illusion, virus vs. no virus, science experiment gone wrong vs. ancient evil, baby as victim vs. baby as killer, boy as good vs. boy as evil (also, boy as child vs. boy as man), Aeon knows more than Trevor vs. Trevor knows more than Aeon, and so on — and it’s never clear (to us or Aeon) where things really stand (for all we know this whole thing is Trevor’s elaborate mindfuck/practical joke at Aeon’s expense, with the boy and baby merely players or props). If there is any clear realization at all, it is merely that waking up repeatedly on a stone slab drenched in blood is ultimately not all that much more puzzling or bizarre than waking up repeatedly on a Sealey Posturpedic Mattress.”

The story

Aeon is searching for a baby. She trips and falls through the ground into an underground science lab called Coloden, where everyone is dead except for a strange boy.

Soon it’s clear that she’s trapped in a time loop. Events repeat. She wakes up on a bloodstained altar over and over. Plot points and characters are volleyed at the audience: a baby, a monster, and a vial (which may contain a consciousness-altering virus), and several dead scientists. It’s not clear how these relate to each other, and established facts seem to change every time Aeon goes back into the past.

What’s going on? What were the scientists working on? How did they die? Is Aeon losing her mind? Is she infected with a virus? For that matter, is she now dead herself?

Every time you think you’re making sense of “Chronophasia”, the rug is yanked out from under you. Finally, Aeon gives up, mistrusting everything she sees. The facts seem as hollow and insubstantial as dead leaves. Finally, the entire husk-narrative is blown away by a rising wind of textual and literal insanity, with Aeon losing her identity in a sea of possible selves.

Then comes a final scene. Aeon is depicted as a regular suburban soccer mom in 21st century America, taking her kid to a baseball game.

The end. Tune in next week for The Maxx!

Creatophasia

Showrunner Peter Chung had almost no involvement with “Chronophasia”.

The first draft was by storyboard artist and animator J Garett Sheldrew (who tragically passed away in September). He wrote a “whodunit” mystery where Aeon wakes up covered in someone else’s blood, and tries to unmask the murderer. As the suspect list narrows, she confronts the truth that maybe it’s her.

MTV deep-sixed this idea, deeming it too violent.

Peter Gaffney rewrote Sheldrew’s script into a rambling sci-fi tale, sprinkled with references to things like the Diamond Sutra and Julian Jaynes’ The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. It’s possible that these philosophical digressions are red herrings, not to be taken seriously. Other story ideas may have come from director Howard Baker, executive producer Japhet Asher, and possibly Peter Chung.

Bits of Sheldrew’s original script still exist in the episode like fossils. For example, the monstrous baby is his. I’ve heard that the corpses are his, too – they were supposed to be freshly-killed, but MTV had them changed into (less gruesome) mummies.

“Peter G didn’t like having to incorporate the giant man-eating baby into the script, but that was one element Garett would not let go. I honestly don’t think he had a rational reason for its presence, other than it representingf fear of the responsibility of parenthood (see Eraserhead)– one of Garet’s [sic] infinite anxieties , and no doubt one of Aeon’s as well.” – Peter Chung((Ibid.)

Needless to say, the end result is pretty schizophrenic. Its writers pulled it in many conflicting directions (gothic horror, science fiction, trippy new-age philosophy), and it suffers more than usual from MTV censorship. Many viewers failed to realize that the grayish-blue fluid is blood, believing it instead to be fluid from the broken vials.

It’s very well drawn and animated, and has some striking background art. The abandoned laboratory in Coloden is one of the show’s eeriest locales. Even if “Chronophasia” ultimately means nothing, it’s certainly good at creating an appearance of depth.

The story treads ground that no other Aeon Flux episode does. Only “Chronophasia” references things that happened elsewhere in the show (Aeon dreams of Rorty, Una, and so on). Only this episode implies the existence of the real world. And Aeon’s supposed motive – rescuing a baby – is uncharacteristically heroic for her.

Aeon Flux was released on DVD in 2005, and Peter Chung rewrote and re-recorded the dialog of several episodes. It’s notable, perhaps, that he left “Chronophasia” completely untouched (aside from some digital effects).

Was he satisfied with “Chronophasia”? Did he deem it such an incoherent mess that it wasn’t worth touching with a ten foot pole? Both at once? Make up your own mind.

The episode is essentially a series of open questions. I will try to offer thoughts on them.

Is Aeon dead/dreaming?

I don’t believe so.

The camera takes an omniscient viewpoint. There are scenes of Trevor exploring the caves and interacting with his men, for example. We’re not solely getting Aeon’s perspective, as we would if she was dreaming.

At the start of the episode she falls from a great height. It would seem impossible for her to survive such a fall…but the shot fades to black with a soft rustling sound, as if to imply she’s landing on something soft (like leaves). Aeon visibly sickens as the episode progresses. Would that happen if she was dead?

The episode sees Aeon caught in a sort of time loop. That’s not what death is. Death is the opposite of a loop, it’s the end!

Furthermore, although the virus/boy/whatever causes you to slip into alternate timelines, Aeon can still control her circumstances, to a limited extent. She’s not a puppet.

In one timeline, she’s overwhelmed by Trevor’s soldiers. In another, she overpowers them and steals a gun. In one, she ties the boy to the ladder to stop him causing mischief. In another, he’s still tied up (this time to the roof). Things that happen in one universe seem to cast rippling echoes into the next one. And again Aeon keeps getting sicker. She’s not just stuck in a loop. For better or for worse, things are not stable, and the center cannot hold.

There’s a lot of fan theories that the boy/baby represents death. I find myself reluctant to accept this. For one thing, it just seems shallow – the kind of faux-profound film student writing that Aeon Flux normally avoids like the plague. The episode certainly toys with the idea that she might be dead, but only as a stalking horse for its real thematic concern, which is confusion and ambiguity.

Are you dead or alive? The real horror is that you might not be able to tell.

Who is the boy?

He’s the episode’s most important character, and the key to whatever’s happening to Aeon.

Everyone else – Aeon, Trevor, his men, the baby – ends up mangled by the changing timeline. Dead, alive, insane, or altered beyond recognition. Only the boy remains unscathed: the gravity source that all else wheels around.

He claims to have been around forever, and to have killed everyone in Coloden.

Boy: I was here first, before they came here with their experiments. A virus that produces human happiness.

Aeon: So you killed them.

Boy: Except you.

(Some fun ambiguity: the boy could either mean the experiment involved a virus to produce human happiness, or he could be talking about himself.)

He’s clearly a very old being (many of his words are quotes from things like Othello), but he’s also boylike and immature. He ogles Aeon as she undresses. Later, he half-heartedly attempts to seduce her, his bravado hilariously falling apart. “I will have you! …No, not like this!” It’s a pretty true to how twelve year old boys react around women – that mix of lust and horror.

He says “My time is not your time.” and that’s probably the truth of it. He’s both young and old, an entity for whom age doesn’t quite exist.

Honestly, the child actor’s delivery is pretty flat, and this makes it hard to judge the intended emotion of some of his lines. Maybe that was the direction, though.

Who is the baby?

Aeon’s stated motivation is to rescue a baby girl.

“[she’s] one of the test subjects from the little experiment. I came here to get her out.”

There are several reasons to be skeptical of this.

She doesn’t act like she cares about the baby. She explores Coloden and sees evidence of destruction everywhere: dead bodies, shattered glass, and melted blast-doors. Something horrible has obviously happened and she should be heartsick with worry.

…Instead she wastes time changing outfits and goofing around with the boy.

When Aeon comes to the lab and sees the broken vials, she says: “Looks like it’s all been taken care of. Came here for nothing.”

The “taken care of” line makes me think she didn’t come for the baby but for the virus. It’s a key to universal consciousness or happiness, and Aeon traditionally abominates such things (cf “The Demiurge”, “The Purge”, “Ether Drift Theory”). It’s most probable that she’s there to eliminate the virus and all of its works – including the baby, if necessary. As Trevor says, “all she knows is how to destroy”.

I’ve seen people speculate that Aeon is the baby’s mother. If so, she behaves like no mother I’ve ever seen. She displays little interest in the baby’s welfare. She speaks of it conversationally, as though it’s a game piece. She has no personal attachment to the child, and probably only wants it because it’s had contact with the virus.

In any event, the baby is alive, but grotesquely mutated. The boy refers to the baby as “the waker”. “She’s very strong. You have to be good to her.” But then the mutated baby dies, and the odd events continue.

The baby is depicted as a classic teeth-gnashing movie monster, and it’s apparently killed some people (it’s surrounded by bones and “blood”). But I don’t see how it could have committed the stranger events in Coloden – the lapses in times, the mummified corpses, the insanity. My guess is that the baby, like the vial, is only secondary to the events at Coloden, not central to them.

What does the virus do?

We don’t know, Aeon doesn’t know, and little dogs don’t know. Perhaps nothing.

Strange events have already started happening to Aeon before she makes contact with the vial. Either the virus has already saturated the facility (so why care about that one particular vial?), or it’s a red herring, unrelated to what’s going on. Aeon’s first blackout after arriving in Coloden isn’t triggered by the vial, it’s triggered by her seeing the baby.

For what it’s worth, Peter Chung suspects that the virus/vial doesn’t matter.

“The clear fluid comes from the broken vial and Aeon’s contact with it may be connected to her confused state, but is more likely a red herring representing an object on which to project external causation.”

It’s a clever bit of narrative sleight-of-hand. We think the vial’s important, so whatever something odd happens, we attribute it to the vial. Just as anyone who dies after breaking into a pharoah’s tomb has suffered from “the curse of the pharoahs”, instead of, say, lung cancer.

What’s it really about?

Where “Chronophasia” seems to fit best is as a study of reality, and how little of it actually exists in an actual noumenal sense.

To be clear, some reality exists. At the bottom of the universe is a physical substrate of atoms and forces and things like that. But on top of this is a complex interpretative layer, things which we define into existence. When does bread become toast? When does a living person become dead? How many sand grains make a pile? The answer depends on the asker, and the context.

Philosophers have long mooted the idea of a “multiverse”, generally relying on the Many Worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. What’s often missed is that we’re living in a multiverse right now. Every object in the universe has a billion perceptual shadows flying out from it. I look and see a tree. You look and see a different tree. People have varying retinal cone mosaics and ability to perceive color and none of us see it the exact same way.

Even aside from this, the underlying nature of the tree is ambiguous. I might just see “a pine”, a botanist would see Pinus sylvestris of the Coniferae order, a Wiccan would see a source of earth magick, and a freezing person would see firewood. A blind man would see nothing at all: their sensory picture of the tree would be complete at the feel of rough bark, the smell of pine cones, and so on. Like Aeon in the penultimate scene, the tree keeps morphing and mutating while remaining unchanged. To be something is to be everything.

Even when facts are agreed on, context can totally flip how we understand them. Imagine you see a person threatening another with a gun. You are scared by this. But then you step back and see a stage, and footlights, and a proscenium. You’re no longer scared, because the context for these events has changed: you’re watching a play. This, in neuro-linguistic psychology terms, this is a “frame”. And there are as many frames as there are viewers.

Reality is both fixed and in flux, a single base number endlessly operated on. “One thing contains everything” seems to be the lesson of “Chronophasia”. It’s a nifty sci-fi take on the impermanence of the world around us.

Aeon Flux’s body is a set of atoms that could be sleeping or awake or alive or dead. If the quantum dice had fallen differently she would indeed be a regular woman, taking her son to a baseball game. And perhaps she is that to someone – think of how Trevor sees her as a romantic partner, while the baby only wants to kill her. Her essence (to her chagrin) is largely out of her hands, and depends on frames and interpretations.

These questions are near and dear to Aeon Flux. Peter Chung is the son of North Korean defectors, and although the Bregna/Monican border divide seems inspired by North (mostly due to the show’s architectural style), in truth it’s more inspired by North and South Korea. The border line is imaginary, yet you can see it from space. On one side is among the poorest states in the world, on the other is one of the wealthiest. All because of a thing that’s not real. Like two children bouncing up and down on an imaginary see-saw.

Maybe Trevor sums up what the episode is about when he says “So, play it both ways, would you?”

What does Trevor Goodchild want?

Trevor: This particular strain of the virus causes permanent insanity. But don’t worry, Aeon, I’ll take care of you, always.

Aeon: Naturally, I’d prefer to be dead.

Trevor: Odd, the virus has never been fatal. In fact, there’s some evidence. exposure actually extends life. Why, Aeon, you may have another 80 or 90 years of this. Fresh ground pepper?

Aeon: Universal madness? Is that your current project?

Trevor: As usual, Aeon, you only have half the picture. The virus they were working on here does produce…a particularly nasty psychosis, as you’re learning first-hand. The sauce is good, don’t you think? But we believe that at one time, before the dawn of history…a form of this virus existed in every human brain. In fact, it was an essential component of human consciousness. What it produced then was not a madness…but a sense of connection. Of being in and of the world. But somehow, we developed an immunity. That was the fall, Aeon. Ever since, we’ve been missing a part of ourselves.

Aeon: I think your chef uses too much tarragon.

Trevor: Hard to say where the mutation occurred…in the virus or in the human mind, but if we could reverse the process…My project is not universal madness, it’s universal happiness.

Frankly, I’m tempted to ignore everything Trevor says.

He barely knows where Coloden is, and has only sketchy information about its operation (“According to my information, this was a working facility three weeks ago.”)…so how does he suddenly know so much about the virus? And if Aeon’s infected, is it safe for him to interview her face-to-face, without a Hazmat suit or even a facemask?

His speech about restoring universal happiness has the ring of noble-sounding bullshit. He’s clearly just as interested in acquiring Aeon than whatever his mission is (like always, in other words).

He makes some odd leaps of logic. When he sees Aeon in the jungle he assumes she’s looking for the vial. This is correct, but how did he know that? When he finds the laboratory retort stand with the fifth vial missing, he assumes that Aeon must have taken it, based on no evidence.

He has conflated his quest for the vial into a quest for Aeon, whether he knows it or not. Trevor doesn’t need a virus to unstabilize his view of the world, he’s confused enough already.

Who wrote the final scene of “Chronophasia”?

That’s the big question mark.

Gaffney says he doesn’t know who wrote it, and since he worked from Sheldrew’s script, this necessarily eliminates Sheldrew as a possibility.

In the DVD commentary track (which contains Gaffney, Baker, Chung, and Asher), none of them take credit for it.

So where’s it from? Does anyone know?

Also, rewatching “Chronophasia” again, I realized that I’m (possibly) error when I say there are no material changes in the 2005 DVD re-release.

Below is a VHS recording (top), along with the DVD version (bottom). Note the new translucent fade-to-white, which echoes an effect seen earlier when the vial breaks.

This could suggest a disturbing idea: that Aeon still hasn’t escaped, and is still in the thrall of the virus.

Not Dead. Unborn

The secret to a successful magic trick is to make the audience look at one hand, while you perform the trick with the other.

“Chronophasia” achieves this by growing about sixteen new hands and five feet, all of which are doing different distracting things. It gives us a lot to think about – too much? – but maybe one of those hands really does hold a magic trick.

1 Comment »