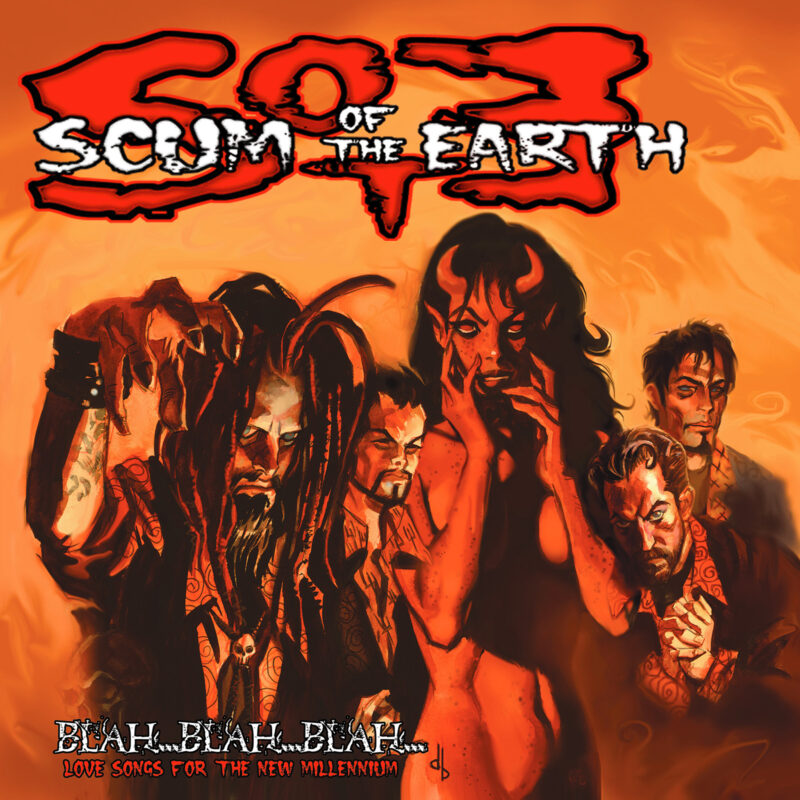

In 2004, Rob Zombie fired his guitarist. This guitarist – who had performed on the multi-platinum Hellbilly Deluxe and had clearly done a lot of the songwriting – immediately formed a new band, Scum of the Earth, along with White Zombie’s Ivan DePrume, and Powerman 5000’s Mike Tempesta.

This kind of “double band” thing is traditionally a way to settle scores and prove who mattered and who didn’t. Would Rob Zombie fail without Mike Riggs? Would Scum of the Earth become the new hotness? Would Bush be re-elected and, if so, would he succeed in “making the pie higher”? These were the questions we asked in 2004.

Spoiler: Rob won. He is still selling out arenas and making movies and touring with balding fifty year old sex criminals. Mike Riggs now works as a tattoo artist. Few remember Scum of the Earth’s inauspicious debut album today, and even fewer will tomorrow.

It deserved better. At least, it didn’t deserve to be totally forgotten. The album is fun. A little cheap sounding, but do you care if liquor comes in a cardboard box if your goal is to get wrecked on it?

Blah…Blah…Blah…Love Songs for the New Millennium demonstrates one thing: the Hellbilly Deluxe sound was indeed Riggs’. You hear it everywhere: the slamming, grooving riffing style, the electronic rhythms, the stop-start dynamics. This is unmistakably the brain (and picking hand) that created “Dragula”. Sometimes the songwriting is uncannily close, such as on album highlight “Murder Song”. When Blah…Blah…Blah… is good (and it is on about half its songs) it sounds far more like Rob Zombie than Rob Zombie’s post-Riggs music, which could be described as “70s nostalgia with about two heavy songs to make the fans happy”.

So what went wrong? Why did the album flop?

Well, larger-than-life shock rock needs a larger-than-life frontman, and Riggs had little charisma or showmanship. Back in the Ozzfest/Family Values days he seemed like a gruesome sideman to Rob, with a hollow acrylic Fernandez guitar that he could fill with blood or rotten meat. But once he had to front his own band he came across as a shy, reticient guy without much to say.

Riggs anti-promoted Blah…Blah…Blah… with truly incredible interviews, such as this one. What makes this project different from any of your previous musical endeavors? “I don’t know…Different people.” What does Rob Zombie think of the band? “I don’t know.” What will you be doing for Halloween this year? “Playing a show somewhere, can’t remember.” He promises to make a second album, and says that it will be “Hopefully, better than the first.”. In a genre where megalomania is virtually a job requirement, this man was hell-bent on discouraging you from listening to his music.

This indifference carries over to the album’s lyrics. Rob Zombie isn’t the greatest lyricist, but he can always be relied on for Burroughs-style lines that send your mind down interesting places. Riggs’ writing is seriously uninspired. Once he’s murdered some sluts and worshipped the devil a few times, he seems to run out of material.

And he cannot sing at all.

He doesn’t have a good voice. That’s the big problem here, particularly as the music is so vocally-driven. He seems to have known it, too: I recall him asking his label to allow him to work with a different singer. They refused, because of some stupid reason that I’ve forgotten and presumably only makes sense to record labels. He should have walked right then. It’s so obvious that this band needed a better singer.

He yelps, slurs, and barks, in a thin and high-sounding voice that’s about three notes deep. The various production tricks (like the way his vox track is slimed up with heavy chorusing) just draw attention to his vocal deficiencies like a blinking engine light.

It gets worse. “Little Spider” and “Give Up Your Ghost” feature acoustic guitars and clean singing. I am proud so say that I have never listened to either song all the way through and I never will.

The production is all over the place. Indie albums often have a fractured, piecemeal quality – they get recorded in various places, when dribbles of money become available – and that’s very apparent here. No two songs are mixed or recorded the same way. The kicks on “Murder Song” are are a healthy +6dB louder than the ones on “Get Your Dead On”. The guitars on “Nothing Girl” have a scooped out Tim Skold/KMFDM character (to the point where they might as well be synths), while “I Am the Scum” sounds like nu metal. The snare drum on “Pornstar Champion” is a digital sample, but the rest of the drums are live.

It’s a bit of a mess. And since Riggs lacks Rob’s major label Rolodex, he can’t paper over his weak spots with guests like Ozzy Osbourne and Tommy Lee and Iggy Pop. A random groupie sings on “Bloodsuckinfreakshow”, along with Riggs’ own son. Apparently the kid agreed to “perform” in exchange for two thousand dollars, terms which Riggs agreed to, on the condition that that the label had to pay him first. They apparently never did, so for all I know, Riggs’ son is still waiting for his two thousand dollars!

So the two big draws of Rob Zombie (the massive production and massive voice) aren’t here. What’s left is Riggs’ musicianship and guitar playing, which carries a lot of these songs. But by the time you get to nothing songs like “Nothing Girl”, you’re just listening to filler. This is a thirty-six minute album that actually runs for about fifteen. It could and perhaps should have been an EP.

I was a big Rob Zombie/Powerman 5000 fan at the time I discovered this – an early version of this site was called The Australian Nightmare, after Rob’s Howard Stern theme song. But this triggered a tyranny of small differences thing in me. There’s nothing worse than a thing you love done just a little bit wrong, and Blah…Blah…Blah… is a lot wrong.

Now that my obsession with Rob Zombie has faded, I can actually appreciate it. It’s forgotten and obscure, but it has its moments, and being dead is no hardship at all for a zombie.

No Comments »

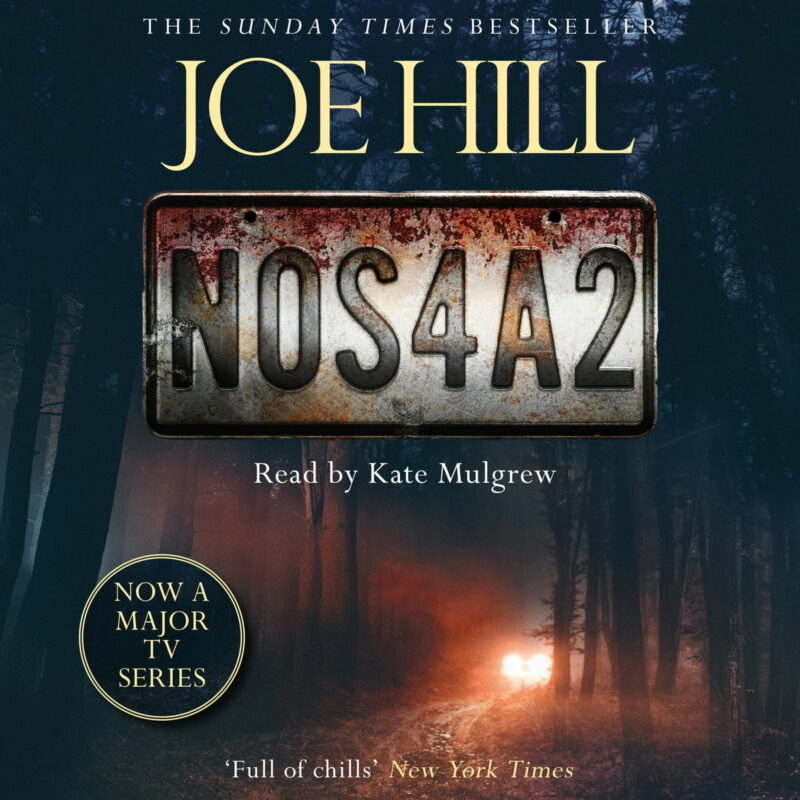

The title shows Joe Hill’s best side: his playful wit. The book is funny at times: and often because it means to be. It also shows his fatal flaw, which we’ll get to soon.

The book’s about larger-than-death pop-villain Charles Talent Manx III. He’s a vampiric creature who kidnaps children in a Rolls Royce Wraith with a NOS4A2 vanity plate. He’s Dracula, John Wayne Gacy, and Michael Jackson at once. Why couldn’t I have been murdered and left on the side of the road by this guy in 1973, instead of that Dennis Rader jerk?

Set against him is Vic McQueen, who also has paranormal gifts: She cross an imaginary bridge and find missing things at the other side. This is described as an “inscape”, a mental shortcut that some creative types exploit (damaging their health in the process). Maybe not the most original or subtle metaphor for drugs, but that’s where NOS4A2 works. The story is bold, brash, and full of color – even if it’s usually color from a spraygun and not a paintbrush.

But the pun in the title doesn’t quite work – nitrous oxide systems first appeared in automobiles in the 1950s, and Manx’s car is from 1938 – and this points to the problem with NOS4A2: it never gains the weight and heft of reality. It’s obviously a construct. The book is too clever, too full of references. It badly wants entry to the gated world of classic horror novels, to the point where it tries to pick the lock.

The plot reads like Stephen King’s ten most famous novels compacted in a hydraulic press. Vampires. Haunted car. Haunted house. Girl with supernatural gift. Ancient evil that feeds of children. Drug metaphor. Creepy undead kids. I was about to say “at least there’s no cornfield”. Then I remembered that there is a cornfield.

Sometimes the namedropping is blatant, such as when we find that Manx’s wintery retreat is in Colorado, or when Bing says “My life for you!” to Manx.

If I’m just lazily listing things, that’s how the book feels, too. While it would be unfair to call it a grinding, soulless list of in-jokes and references like Clown in a Cornfield (the world’s first “young adult” book written exclusively for forty year olds consoomers) the book is deadened by its use of horror cliches. Events in NOS4A2 don’t happen to people, in places. They happen to stock figures in generic settings, most of which are lifted from 1980s books from the author’s own father.

Is this what horror’s supposed to be? I don’t think so.

Horror is meant to be a scalpel to the amygdala. It wakes instinctive fears you might not have been aware you had. It thrives off the unexpected, off dissonance. It can’t become ever become “cosy” or a franchise without losing its soul, but we’re at the point where there’s 20 designated “spoopy ideas” that books variously shuffle around and recombine in various orders, hoping to strike gold again. It’s a real shame. Horror needs to climb out of its own ass.

Another problem is that NOS4A2 is paced very fast. The narrative’s sediment is never allowed to settle. Hill is trying to do too much here – right out of the gate we’re bombarded with various unrelated bizarre, dramatic, or supernatural things (Manx, Vic McQueen’s magic bike, Bing), along with rapid shifts in time and place that leave book’s cohesion in tatters. And there’s no displacement when paranormal events start occurring, because they occur almost from the first page!

Stephen King’s books are usually paced far slower, which gives them a certain stateliness. The nightmarish gross-out scenes are freighted down by a lot of everyday life – nothing happens for an extremely long time in Pet Semetary or The Green Mile, because he’s building up the characters and their world. NOS4A2 thinks it can race through all that in fifth gear, but it really can’t.

In the final pages, the action builds up to an exhilerating climax that goes for broke, takes out a small loan of a million dollars, then spends that, too. Hill’s a gifted natural writer, with an eye for quick, effective characterization. Early on we meet Bing Partridge, a chemical plant worker who might be developmentally disabled. Bing exclusively reads old pre-war magazines and paperbacks, and when he writes a letter, his prose is hilariously stilted and old-timey. This is a subtle but good touch. So is the way Vic goes from idolizing David Hasselhoff to hating him. Lots of writers forget the huge gap between twelve year olds and fourteen year olds, but Hill hasn’t.

But sometimes his characters ring hollow. “McQueen” is an irritating, phoney-sounding name, meant to anchor the book in car culture, and she’s such a congenital screwup that we don’t believe she’d grow up to write a best-selling puzzle book full of brain-teasers. And Vic gets a romantic interest: a big, mellow easygoing from the left side of the bell curve. Yet he’s characterized with a fannish interest in Marvel comics (to the point where he’ll argue what color the Hulk’s skin should be). Have you ever met a comic book fan? They’re not mellow and easygoing. They’re angry, vicious, and highly strung. Lou Carmody caring about comic books is about as believable as Barney Gumble running The Android’s Dungeon.

Most of the book is entertaining and well written. I just don’t enjoy (or respect) a lot of what it’s trying to do. NOS4A2 is loudness-war Stephen King, with the bad amped up far more than the good.

No Comments »

Social media thrives on battles against imaginary enemies. George Santayana said that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. Online, we are condemned to repeat the Gulf of Tonkin.

Everywhere on Reddit, Twitter, and Tiktok, armies assemble and battle lines are drawn…but the foe doesn’t exist. Or it exists but it’s something really stupid. One crazy person who enjoys eating dryer lint will be spun into an imaginary movement of pro-dryer lint eaters that must be stopped at all costs by us, the brave anti-dryer lint warriors, before their dangerous dryer-lint munching agenda takes over the world.

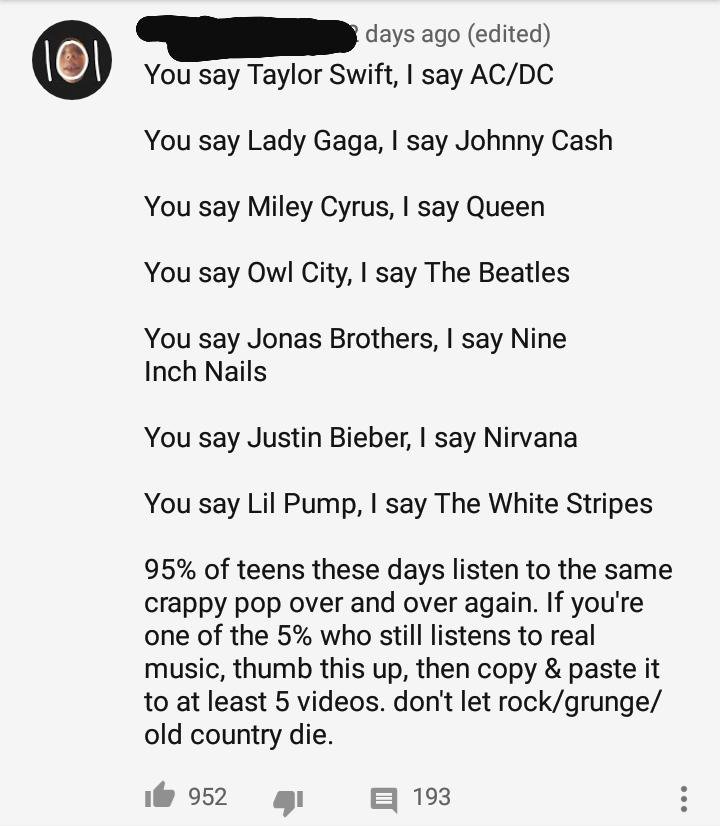

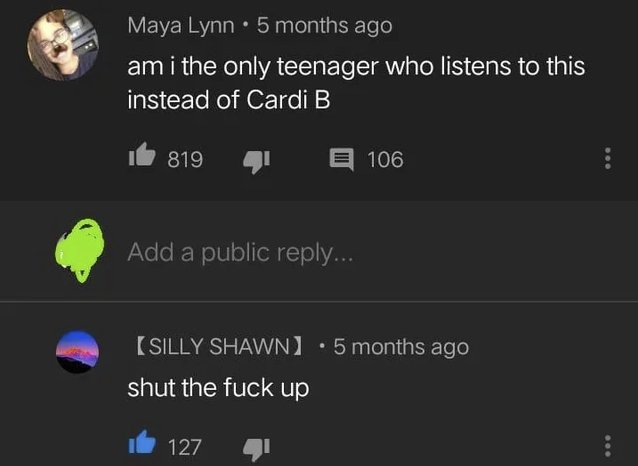

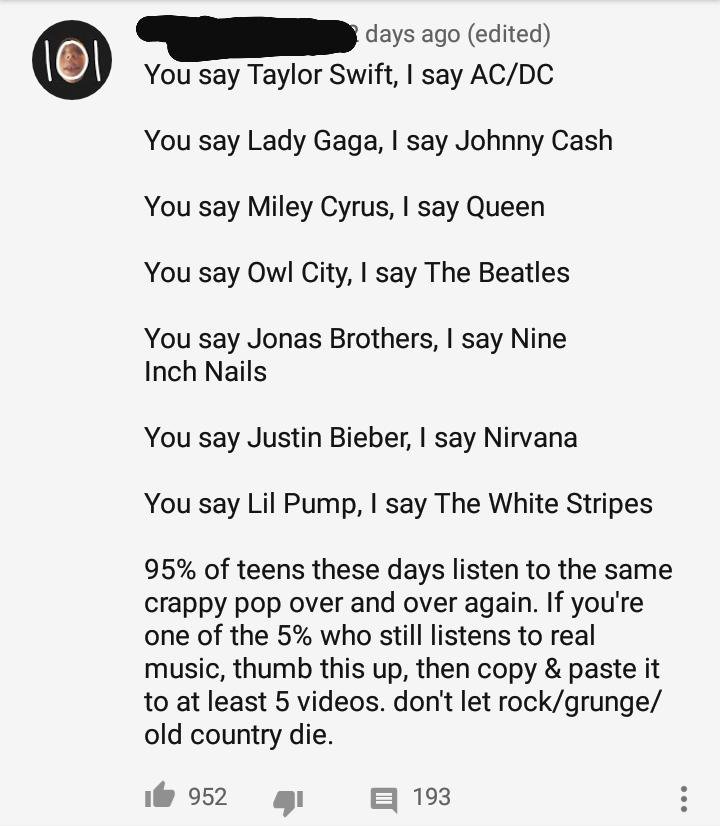

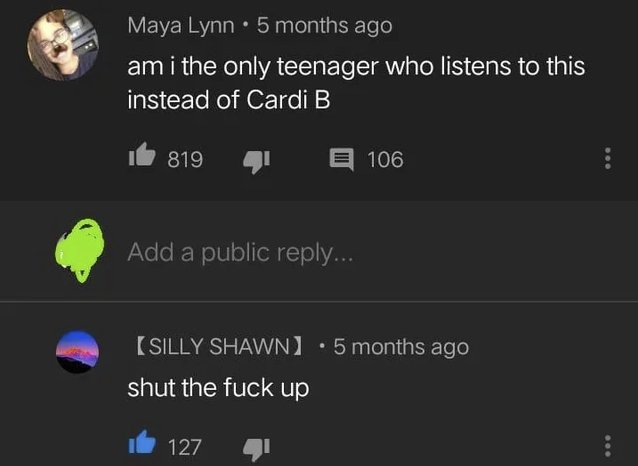

A good example is pop music. For years and years and years you’d glance into the Youtube comments of a classic rock song and see this cancer voted to the top.

You get the idea: fans of classic rock (like Nine Inch Nails…?) bravely standing up to some supposed horde of brainwashed mainstream pop lobotomy patients.

But you never saw any pro-mainstream pop people in the Youtube comments. You never saw anyone say “Justin Bieber rules, the Beatles drool!” The rockists were fighting a one-sided battle against an imaginary enemy and somehow losing. They came off as deranged lunatics, swatting at spiders only they could see.

The Beatles became a watchword for the good old days when men were men. When lyrics had depth, when musicians had talent and soul and played live with real instruments. Not like today’s music, which is mass-produced commercial crap created by some dead-eyed Swedish DJ named Johann Häågflåärt.

This is all just fanfiction. The Beatles wrote many shallow, mindless songs aimed at a commercial market, and they did sloppy work sometimes – on “Hey Jude” you can clearly hear McCartney say “fuckin’ hell” after missing a piano chord.

The Beatles didn’t play live out of some commitment to artistry but because there was no other option: if Protools had existed in 1967 they would have used it. They took advantage of technology regarded as inauthentic back in the day, such as guitar distortion.

Largely as a reaction to rockist smugness, a counter-movement of “poptimists” appeared. These were people like FreakyTrigger’s Tom Ewing, who enjoyed modern pop music and felt it was worth defending.

Sadly, many poptimists overcorrected and became equally smarmy (and equally brainwormed by politics). Imagine listening to lame boomer crap like the Beatles in 2022. Ew! Don’t you know John Lennon hit his wife? I’m glad nobody from our generation does things like that.

Poptimists branded themselves around progressivism. They wanted to believe that listening to glurge at the top of the Spotify charts constituted a revolutionary act. But, like wearing clothes made in a sweatshop, consuming music created by women or black people is simply not, in and of itself, a particularly heroic act.

The entire war is absurd. Some people enjoy both The Beatles and Taylor Swift. Others enjoy neither. Some enjoy certain Beatles songs more than certain Taylor Swift songs and vice versa. Others regard them as fundamentally alien from each other – varelse, as Orson Scott Card would put it – and beyond comparison. Still others are breaking large stones into smaller stones in an Zimbabwean mine for one hundred trillion dollars a day and have never heard either of them. The world is massive and has many sets of ears, all of them unique.

But war is manichean and abhors complexity. Just as Imperial Japan had nearly no cultural affinity with their German allies, all this uniqueness gets marshalled into some grand “us vs them” battle for society’s soul. Beatles vs Taylor Swift. Tradition vs progressivism. You have to choose a side, Neo. There’s no purple pill.

The truth is, the entertainment complex has only one side. It swallows both the Beatles and Taylor Swift. It swallows the whole world.

You are psyopped if you imagine that your “Beatles vs Taylor Swift” feud means anything to anyone who makes anything. The Beatles often hung out and partied and collaborated with media created “enemies” such as the Monkees and the Rolling Stones, and I’m sure that if Taylor Swift had lived in the 60s, they would have collaborated with her too. Why wouldn’t they? They were all musicians, more alike than different.

Penn Jillette tells a story (in the forward to Howard Kaylan’s biography) of idolizing Frank Zappa…and being shocked when Zappa used the Turtles as his backing band. The hell? Zappa was cool. The Turtles were lame. Was Zappa now a quote sellout endquote???

But soon he realized that it’s foolish to think this way: the entertainment complex doesn’t care about schoolyard cliques. There is not some cool artists table that’s gated off from the rest. High art and low art is a game for critics. To the people who make stuff, it’s mostly all the same.

Lou Reed learned his songwriting craft cranking out surfing songs. Bowie would go from writing progressive rock to exhibiting his penis in a children’s muppet movie. The lines between high and low art get blurred and crossed all the time, and mainstream fluff can be gentrified into “serious art” with little effort: Bowie and Madonna both made their careers out of doing exactly that. Many celebrated masterworks (like the Mona Lisa and the Cistene Chapel) were commissions done for money, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Work-for-hire art can have a human heart beating inside it. That’s the main lesson of Tim Burton’s Ed Wood: that this shitty B-movie director was motivated by the same thing as any director, which is a desire to entertain and move the audience. It only depends on how generous you, the viewer, are prepared to be.

Inversely, lots of “serious art” is created in a spirit of hackish cynicism. I do not believe Damien Hirst has ever been motivated by anything except a desire to make money and belong to a scene.

No Comments »