A polemical essay, written by a layperson, on the birth, rise, fall, rise again (etc) of the Robin Hood. I can be reached for comments on (917) 756-8000 or at contact@win.donaldjtrump.com.

Knave Sir Robin

Robin Hood is a legendary English outlaw who hid in a forest. The legend of the legend hides in a different forest: one made of pulped paper.

The character exhibits a fascinating tension: he’s the world’s most famous folk figure, but we know almost nothing about how he was created. He’s the Superman of the Late Middle Ages, but there’s no Action Comics #1 for Robin Hood. Researching the character’s origins is like shoveling smoke. Even by legendary standards he’s a ghost: we can be more certain about King Arthur’s formation (hundreds of years earlier) than we can about Robin’s.

When was he created? By whom was he created? Was he created?

As with Arthur/Artuir/Artorius, it’s faintly possible that Robin was once a real person. The 1225 York assizes mention a “Robert Hod” fugitive whose goods (totalling 32 shillings and 6 pence) were confiscated by the crown. There’s no reason to believe that this (or any other) man was a “historical” Robin Hood. Robert/Robin was the fourth most common name in Medieval England, and Hood not uncommon. Think of the difficulties modern historians would face in writing about a “James Smith”.

There’s a stronger case that the legend dates from this period. In 1261, a fugitive called William (son of Robert) is referred to in a royal document as William “Robehod”.) Then there’s a ‘Gilbert Robynhod’ in the Sussex subsidy roll of 1296. This unusual concatenation of forename + surname into a new surname suggests a false or adopted title…so adopted from where?

History is full of Robins and it’s easy to make false connections. There’s a 1282 French lyric poem called Le Jeu de Robin et de Marion (“The Play of Robin and Marion”), but as there’s no French tradition of Robin Hood stories and Maid Marian doesn’t exist in the earliest English tales, historians regard this as an unrelated figure. Ditto for the folk figure of Robin Goodfellow/Hobgoblin. Exploring a maze means getting lost in false ends; exploring history means getting lost in false beginnings.)

In 1377 we hit paydirt: William Langland’s Piers Plowman contains a character who knows the “rhymes of Robin Hood”. This is a huge break: Robin Hood’s legend unequivocally existed by the 14th century, and he was apparently famous enough for Langland to name-drop without explanation.

A century later we find the first surviving copies of the tales themselves, including:

Robin Hood and the Monk (>1450?): Robin is captured while at his prayers in St. Mary’s in Nottingham. Little John hatches a plan to free him.

Robin Hood and the Potter (<1503?): Robin, disguised as a potter, outwits and humiliates the Sheriff.

Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne (<1475?): Robin crosses blades with a vicious hired killer.

Robin Hood and the Sherrif of Nottingham (<1475?): a fragment of a play that seems to be telling the same story as Gisborne. Robin Hood was a common figure for plays – there’s a record of one performed in Exeter in 1426-27.

Robin and Gandelyn (1450?): an eerie poem where Robin shoots a deer with his bow, and is slain by a mysterious arrow in turn.

A Gest [Tale] of Robin Hood (1493-1518?): a rambling series of adventures that’s clearly multiple stories joined together

Here, we see Robin Hood, 1st Draft. They’re fragmentary and contradict each other a bit. Does Robin live in Sherwood (Monk), or Barnsdale (Gest, Gisborne, Potter)? Why is the Nottingham Sheriff chasing Robin eighty miles beyond his jurisdiction (Gest)?

Robin’s character is all over the place in these stories. He’s depicted as a comic buffoon, a devout man of God, and a thuggish murderer. In none of them does he steal from the rich and give to the poor. The Sheriff of Nottingham isn’t an obvious villain but a lawman doing his job.

The morality is gray. Gest has the most benign depiction of Robin (ending lines: “For he was a good outlawe / And dyde pore men moch god”). Contrast with Monk, where the “good outlawe” cheats Little John out of a bet. Or Potter, where he tries to rob a passing traveler of forty shillings. Or Gisborne, where he decapitates a man, mutilates his face with a knife, and sticks his head upon his bow’s end.

Small details clarify Robin and his High Medieval world. Gest states that the king is Edward (presumably, one of the first three Edwards, who reigned from 1272-1377). Additionally, its rhymes only work with a modern long e vowel (“tree” / “company”), so it likely dates to after Jesperson’s Vowel Shift (around 1400).. The simple, repetitive language found in many of these tales suggests an oral origin.

It’s easy to imagine a wandering minstrel dropping local names and figures into his ballads to win over his audience that night, and easy to imagine a composite Robin Hood patchworked out of bits of prior literature. He fits into the nascent genre of outlaw stories (inspired by real figures like Hereward the Wake and William Wallace), and there are some “proto-Robin Hood” stories that possess the character’s spark if not his name. The tales contain tropes common to the period, such as disguising oneself as a potter. And some of the vaguer manuscripts (such as Gandelyn) might not even be about Robin Hood. It’s a common name, after all. A nasty name.

Regardless, this version of Robin was soon to die.

The English public came to love the scruffy outlaw, and by the 15th century Robin Hood stories were firmly esconced as part of the May Day games, enjoyed by rich and poor alike. He appeared in plays, lyrics, songs, and prose poems. The omnipresent references to games and contests feel a lingering part of those years. Robin became a shared, communal figure. If Robin was ever the creation of a single man (unlikely), then this certainly had stopped mattering by the Late Middle Ages. He belonged to everyone. If he was originally meant to be a villain, it proves that you can’t sing of a monster without the monster becoming a hero.

Robin’s “Bigger than Jesus” moment came in 1405, when an unknown Franciscan friar grumbles in Dives and Pauper that people would rather hear tales of Robin than attend mass.. Next to forbidding figures like Prester John and Beowulf, bowed heavy under the weight of myth and legend, Robin was a normal, down-to-earth figure. He’s flawed, foolish at times, and relies on his friends to save him. Although he’s skilled at fighting (interrupted at his prayers in Monk, he snatches up a Zweihänder and kills twelve men with it), he’s not invincible. People often best him both at swordplay and archery. In other words, he’s like us.

Years passed and the final refining touches to Robin’s myth were added. New characters (such as Friar Tuck and Maid Marian) were folded in, while others (such as Much the Millar’s Son and Richard atte Lee) were cast and are now almost forgotten. The character was reimagined to better fit audience tastes. He became less brutal, and more recognizably heroic. He came to embody English ideals of justice and fair play.

But he lost something of himself in the process.

The Gentrification of a Legend

“Robin vs Arthur” is a perennially popular term paper topic. They seem made to be compared. Camelot vs Sherwood Forest, Merry Men vs Knights of the Round Table, Friar Tuck vs Maerlin, Maid Marian vs Guinevere. Their similarities highlight their differences, and their differences their similarities.

Arthur (as per Malory) is a conservative hero: a Christian warrior-king who claims the throne in an age of decadence and chaos and restores Britain to her former glories. His legend is one of chivalry; of noblesse oblige; of romanticism. He wants to Make Britain Great Again.

Robin, by contrast, cuts a very modern figure. Is stealing money wrong? That depends on who you are, who you’re stealing from, and what you do with the money afterward. To Robin, morality isn’t decided by absolute rules but by the power relations between the two parties. To put it crassly, King Arthur votes Tory and the Robin Hood votes SWP.

So it’s interesting to see the chaotic, Puckish figure of early Robin gradually get smoothed out into a “safe” (nonthreatening) romanticised version of himself. This echoes Pinkerian ideas of how civilization works: in the long run, the Empire always wins, with rebellious elements destroyed or assimilated as neutered parodies of themselves. The cult that doesn’t die becomes a religion. The sorceror that doesn’t die becomes a scientist. The knave that doesn’t die becomes a kingsman. Does the Robin Hood that doesn’t die become an Arthur?

A good example of this is Robin Hood’s bloodline. In the first stories, he’s a yeoman – one social rung above a peasant. The fact that he’s robbing travelers on the road to survive indicates a marginal place in society. But I guess some people didn’t like the idea of a smelly commoner doing interesting things, and in the 16th century there were retcons to make him a noble.

In Richard Grafton’s Chronicle at Large (1569), Robin is now an earl. At the century’s end Anthony Munday wrote two plays where Robin is the Lord of Huntingdon. By the time of the Stuart Restoration he can seem somewhat pathetic, such as in the 1661 play Robin Hood and His Crew of Souldiers, where he grovels before a messenger of the king.)

This is now the dominant form of Robin Hood’s backstory: he’s a dispossessed noble fighting against the bad Prince John until the true king arrives. He’s not against the king. He’s a supporter of the king. His robberies and slayings are justified because they’re committed against an usurper. In other words, his fate was to have the older, Arthurian ideal of heroism grafted into his body.

These days, with the nobility in retreat and upper class becoming a slur, some might prefer the earlier Robin. Even if he’s a brutal killer, he’s the people’s brutal killer.

This argument can be overstated. Even the early version of Robin is still gallant and respectful toward his social betters. In Gest, he tells his men not to harass yeomen, squires, husbandmen or knights. And although Robin is frequently set against monks, he’s also deeply pious – the motivating action of Robin Hood and the Monk is the hero’s desire to pray at Nottingham. He quarrels with and cheats his friends, but he’s also fiercely loyal. In general, his antisocial acts have selfish motives: they’re not some Hobbesian political statement. Many of the rabble-rousing populist elements to the Robin myth (like rebelling against oppressive taxes) are not found in the early stories, but the later ones.

But still, Robin and Arthur feel like they exist on opposite sides of a ravine that cannot be crossed. Where Robin seized greatness, Arthur was born to it. He didn’t pull the sword from the stone because of his strong muscles. As a child, he didn’t have strong muscles – that’s the point of the story! It’s a David and Goliath fable, where success against overwhelming odds clearly proves that God is on his side.

Contrast this with Robin Hood’s usual shtick: challenging people to games and contests of skill. Sometimes he’s disguised. The fact that he’s Robin Hood doesn’t matter – his deeds speak for themselves. His weapon, the powerful English longbow, is itself a symbol of merit over blood. The humblest bastard ever born could slay a noble with nothing but a strong arm and a clear eye. Or hell, why not a king? “God made some men tall and some men short. Sam Colt made all men equal.”

Just the same, this idea is interesting in its implications. If Robin Hood is some meritocratic folk figure, would he even need to be English?

Wale Tales

Stephen Lawhead, in the afterword to his novel Hood, posits that the original Robin Hood was Welsh.

Quoted at length because I find it interesting:

Within two months of the Battle of Hastings (1066), William the Conqueror and his barons, the new Norman overlords, had subdued 80 percent of England. Within two years, they had it all under their rule. However-and I think this is significant-it took them over two hundred years of almost continual conflict to make any lasting impression on Wales, and by that late date it becomes a question of whether Wales was really ever conquered at all.

In fact, William the Conqueror, recognising an implacable foe and unwilling to spend the rest of his life bogged down in a war he could never win, wisely left the Welsh alone. He established a baronial buffer zone between England and the warlike Britons. This was the territory known as the March. Later, this sensible no-go area and its policy of tolerance would be violated by the Conqueror’s brutish son William II, who sought to fill his tax coffers to pay for his spendthrift ways and expensive wars in France. Wales and its great swathes of undeveloped territory seemed a plum ripe for the plucking, and it is in this historical context in the year AD 1093) that I have chosen to set Hood.

A Welsh location is also suggested by the nature and landscape of the region. Wales of the March borderland was primeval forest. While the forests of England had long since become well-managed business property where each woodland was a veritable factory, Wales still had enormous stretches of virgin wood, untouched except for hunting and hiding. The forest of the March was a fearsome wilderness when the woods of England resembled well-kept garden preserves. It would have been exceedingly difficult for Robin and his outlaw band to actually hide in England’s ever-dwindling Sherwood, but he could have lived for years in the forests of the March and never been seen or heard.

This entry from the Welsh chronicle of the times known as Brenhinedd Y Saesson, or The Kings of the Saxons, makes the situation very clear:

Anno Domini MLXXXXV (1095). In that year King William Rufus mustered a host past number against the Cymry. But the Cymry trusted in God with their prayers and fastings and alms and penances and placed their hope in God. And they harassed their foes so that the Ffreinc dared not go into the woods or the wild places, but they traversed the open lands sorely fatigued, and thence returned home empty-handed. And thus the Cymry boldly defended their land with joy.

That, I think, is the Robin Hood legend in seed form. The plucky Britons, disadvantaged in the open field, took to the forest and from there conducted a guerrilla war, striking the Normans at will from the relative safety of the woods-an ongoing tactic that would endure with considerable success for whole generations. That is the kernel from which the great durable oak of legend eventually grew.

Finally, we have the Briton expertise with the warbow, or longbow as it is most often called. While one can read reams of accounts about the English talent for archery, it is seldom recognized-but well documented-that the Angles and Saxons actually learned the weapon and its use from the Welsh. No doubt, the invaders learned fear and respect for the longbow the hard way before acquiring its remarkable potential for themselves.

[…]

Taken altogether, then, these clues of time, place, and weaponry indicate the germinal soil out of which Robin Hood sprang. As for the English Robin Hood with whom we are all so familiar… Just as Arthur, a Briton, was later Anglicised-made into the quintessential English king and hero by the same enemy Saxons he fought against -a similar makeover must have happened to Robin. The British resistance leader, outlawed to the primeval forests of the March, eventually emerged in the popular imagination as an aristocratic Englishman, fighting to right the wrongs of England and curb the powers of an overbearing monarchy. It is a tale that has worn well throughout the years. However, the real story, I think, must be far more interesting.

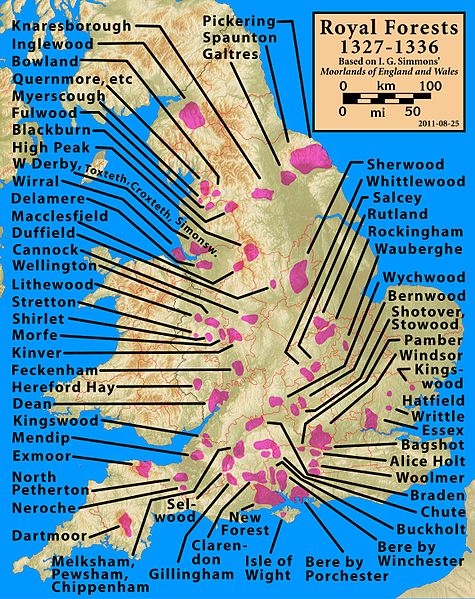

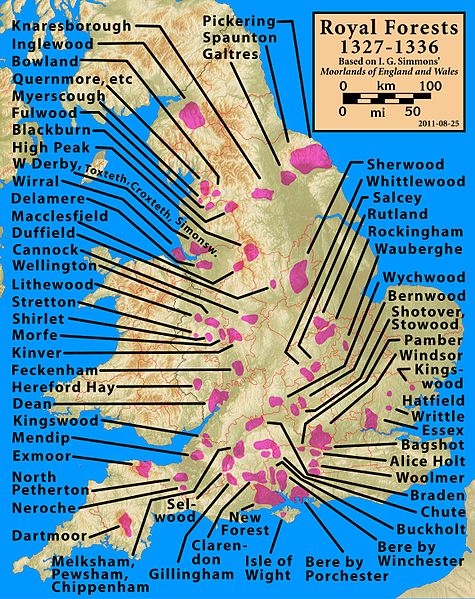

Robin Hood, a Welsh icon? Intriguing if speculative stuff. Some of his claims seem a little over-argued. The “ever-dwindling” Sherwood was still one of the largest preserves in England as of 1327-36.

And if Robin’s legend was merely the sparks thrown off by the Welsh/Norman conflict, why has so little of this context survived in the stories? The locations associated with the Robin Hood stories (Nottingham, Locksley, Sherwood, Rockingham, Barnsdale, and so on) are all many days’ march away from the Welsh border. How did the tale migrate so far, while leaving nothing of itself in Wales? It’s as odd as the modern US/Mexico border tension birthing a Chicano folk figure who’s only spoken about in Wichita, Kansas, but never in San Diego or Ciudad Juárez.

But there’s something that Lawhead doesn’t mention.

In the early 13th century (almost certainly before the start of the Robin Hood legend, in other words), a prose narrative called Fouke le Fitz Waryn was written, based loosely on the life of Fulk FitzWarin III.

The historical Fulk III is interesting in his own right. Essentially, in 1200, King John refused to renew Fulk III’s hereditary title to Whittington Castle, and in 1201, Fulk led an outlaw band in revolt against the king. He skirmished with the crown for years before being granted a pardon (and the rights to Whittington Castle) in 1203. Fulk III seems to have been a troublesome fellow. This was only the first f many issues he provoked, which culminated in Henry III saying “May the Devil take you to hell.”

In Fouke le Fitz Waryn we meet a romantic cipher of Fulk III who’s very similar to Robin Hood. The tales are set in the woods, and there are adventures aplenty: quests, disguises, kidnappings, monsters, magic, and mischief.

He’s no hero, but he has a sense of mercy (and irony). At one point, Fulk and his outlaws ambush the king’s hunting party while disguised as peasants and coal burners. “And Fulk and his company leaped out of the thicket, and cried upon the King, and seized him forthwith. ‘Sir King,’ said Fulk, ‘now I have you in my power, and such judgment will I mete out unto you as you would have done unto me if that you had taken me.'” But then the king pleads for his life, and Fulk lets him go.

Historians have often wondered about the links between Fouke le Fitz Waryn and the later Robin Hood legends. Gest is a particularly cogent reference point: many events line up in both narratives. Both stories have a similar scene where a wealthy caravan is waylaid, the caravaners abducted and terrorized…and are then allowed to dine with the outlaws before being sent on their way with their property. And in Robin and Gandelyn, the murderer of Robin is named as “Wrennoc”, who is the son of one of Fulk’s enemies in Fouke le Fitz Waryn.

Why is this significant?

Because Whittington Castle is on the border to Wales! Fulk III was a marcher lord! He doesn’t appear to have had any Cymry ancestry (the name FitzWarin is Norman French), but this is a big piece of evidence connecting Robin Hood to the political milieau of Wales.

You could also argue for a Scotland connection. Andrew of Wyntoun, writing in about 1420, asserts that Robin and Little John were historic figures living in 1280, in the reign of Edward I. He writes approvingly of their banditry, and connects it with the anti-English sentiment found in Scotland (notable that this is around the time William Wallace was alive, who also dwelled in a wood).

All of this is thin gruel, but it would be a typically black twist of history for an anti-English icon to be repurposed and rebranded as a symbol of English identity. Indeed, if you want a modern parallel to Robin Hood, you might think of a $20 T-shirt with Che Guevera’s face on it.

Laughing to Scorn Thy Laws & Terrors

But focusing on specific details risks missing the Sherwood Forest for the trees. The story of Robin Hood had to come from somewhere, but the figure of Robin Hood can come from anywhere. He’s merely the expression of an idea that has worn well: you can break the law and still be a hero.

His thuggish, cruel side became smoothed away. But this, in part, demonstrates a desire for people to identify with him, to see themselves in this forbidding brigand from the woods.

You can laugh as Kevin Costner plays Robin Hood with an American accent. You can cringe as some weirdo cranks out a term paper arguing that Robin is actually a radical Marxist–Leninist–Maoist revolutionary. But truthfully, such plasticity is a long and honored tradition of the Robin Hood saga. He’s an outlaw. And outlaws dress in whatever garb they need to.

Robin Hood isn’t a character, he’s a symbol. A dagger glinting in the dark. He remains existentially frightening because of what he represents.

If you deem a tax unfair, you should not pay it. If you consider a law unjust, you should not follow it. If a game is rigged against you, you should cheat to win it. From whence does moral law flow? From the mouths of corrupt priests? Kings? Or is it as Robin Hood’s spiritual compatriots Napalm Death: “when all is said and done / Heaven lies in my heart.” It’s said that nature evolves crabs over and over because they’re an effective shape. Stories evolve Robin Hood because they’re such frightening, effective, and inspiring figures.

To a commoner, he’s a hero. To a rich man, he’s a horror movie monster. You’re in a forest. A branch cracks. He’s out hunting you. Your money can’t save you. The bag at your side, bulging with coin, is attracting him like chum to a shark. He doesn’t care that you’re wearing royal blue. It makes you an easier target. You hear a whisper of leaves. A thud. Another man-at-arms falls, scrabbling at the arrow in his throat. He’s coming for you. It’s too late to run.

The profusion of proto-Robin Hood figures littering history speaks to his popularity. Robin Hood can appear anywhere. This itself is an indictment of the human condition. He can be found in 20th century Iraq, having traded his yew longbow for a Dragonov SVD 7.62×54mmR sniper rifle. Or, in 19th century Victoria, wearing a iron helmet made of hammered ploughboards. He’s a relationship, a dynamic, a sparking chemical reaction that society recreates over and over. Anywhere the strong oppress the weak, they sow the dragon’s teeth for more Robin Hoods.

No Comments »

Paul Simon’s follow-up to Graceland is about 75% as good as Graceland and suffers from comparison to Graceland at every turn and here’s a fourth Graceland.

It has many excellent moments, and certainly tries hard enough to to be a big event (it’s stacked with Latin American percussion ensembles, and the production credits list a mind-numbing eighty-six names). But although it can survive being worse than its predecessor, it also can’t escape it.

Graceland, aside from being a pop monster, had weight behind it. Launched in the face of a boycott, it tackled political subjects like apartheid, racism, slavery, and classism, along with Simon’s personal issues – his divorce, his deathspiraling career, etc. It was saying something.

Rhythm of the Saints, by comparison, says little. “I Can’t Run” has a verse about the Chernobyl disaster (nearly five years in the past by then) that doesn’t fit with the rest and has apparently wandered into the lyric sheet by mistake. “Born at the Right Time” snarls peevishly about overpopulation (“Too many people on the bus from the airport / Too many holes in the crust of the earth / The planet groans / Every time it registers another birth”). “The Cool, Cool River” seems to be about environmentalism. It’s half-hearted jabs flung in every direction, few landing with much force.

And given that Graceland had sold over ten million copies by this point, Simon isn’t a scrappy underdog anymore; he’s a mega-selling music phenomenon throwing his weight around. The go-for-broke audacity of the last album is gone. Now he comes off as a rich white guy paying Brazilian drummers to spice up his pop songs.

Paul Simon never musically justifies why he’s doing this, or why he’s chosen to explore this new style. Graceland borrowed from everywhere, but it had a method to it. The intimacy and sweetness of the early Simon and Garfunkel felt mirrored in the mbanqa and township jive of South Africa – with its lavish vocal harmonies and communal aspect – and the links between slave music and 1960s folk/rock are almost too obvious to mention. It all fit together.

By contrast, the showboating tribal drumming of Rhythm of the Saints feels calculated and even cynical on Simon’s part. He’s trying to turn Graceland into a formula he can re-use again and again. “Pop songs, fused with [your country here’s]’s music”. If the cards had fallen differently, we’d be hearing Paul Simon playing guitar along with Mongolian throat singers or Malay gamelan orchestras. It’s just unmotivated exoticism.

The songs are mostly good, leaning as they do into rhythmic textures rather than singalong pop hooks. “The Obvious Child” is the obvious lead single. “Proof” hits hard. “I Can’t Run” is the best song: anxious, itchy, desperate to move but stuck in place. There’s an altered version on In The Blue Light which is also good but sad: it replaces the chicotes and castanets with an orchestral, and in doing so exposes how unnecessary the Latin American elements were to the song.

Rhythm of the Saints was commercially lifted by the aftershocks of Graceland. It shifted a lot of copies upon release (and it was soon certified double-platinum), but its sales rapidly died away. Three singles were released; all of them flopped. These are the typical signs of an album that isn’t selling on its own merits but is instead riding a wave.

I’m too hard on Rhythm of the Saints. It’s huge, elaborate, and detailed. Simon clearly cared deeply about this album, and tried to make it as good as it could possibly be. But through it all is the sound of an artist grasping and scratching to a ragged mountain peak, and finally losing his grip. He can’t help but fail a little. When you’re at the top of Everest, where else can you go except back down to the base camp?

No Comments »