I didn’t “watch” The Song of the South.

You know what I did? I sat my white ass down….and listened.

No Comments »

I didn’t “watch” The Song of the South.

You know what I did? I sat my white ass down….and listened.

No Comments »

“During the Vietnam War, every respectable artist in this country was against the war. It was like a laser beam. We were all aimed in the same direction. The power of this weapon turns out to be that of a custard pie dropped from a stepladder six feet high.” – Kurt Vonnegut

Whether you love or hate Donald J Trump, he easily ranks as one of the ten greatest US presidents in the past decade. He overcame many obstacles on the path to presidency: for example, the arts community didn’t like him.

In alliance with the media, they dropped the mother of all custard pies on his 2016 Presidential run. For example, they called him mean names. Really mean names, like Drumpf and 45 and Cheeto Mussolini and Fuckface von Clownstick. They called him fat and old and made fun of his hair. They drew him as an orange baby, and as a pile of poop. They drew him kissing Putin (because Trump and Putin are gay homos! LOL!). Remember that cameo he had in Home Alone 2? Someone digitally edited him out! Ha! Surely Trump would never recover recover from that.

Shockingly, Trump somehow became President despite this scorched-earth idpol campaign. This was cold water on the mood of the left. “He will not divide us” became “another day in hell”.

This was a symptom of a crisis of faith – the left had simply lost. Nothing was working. Their traditional weapons were all ineffective or had been subverted. The working class were now wearing red MAGA hats, chanting “build the wall!” Social media had become an attack surface for memes about how Hillary was running a Satanic pedophile ring under a pizzeria. And although Trump’s splenetic attacks on the media caused a brief #NotTheEnemy snuggling of the scribbling classes, nobody’s heart was in it. “Why are we pretending to like the media now? Isn’t Trump president because of the media?”

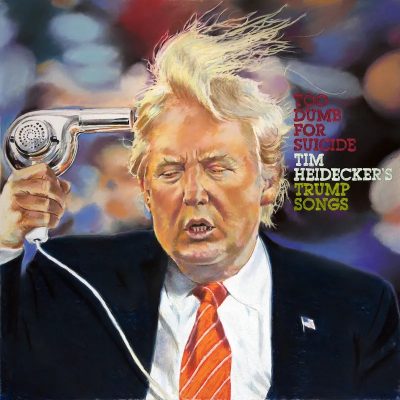

All of this leads me to this album by Tim Heidecker.

Heidecker is an alternative comedian – a term he surely hates. His flagship shows – Tom Goes to the Mayor, Tim and Eric’s Bedtime Stories, and (particularly) Tim and Eric’s Awesome Show, Great Job and On Cinema, reveal a man who enjoys breaking media apart, or folding it in upon itself. On a shallow level, his shows parody badly-made entertainment, but they do more than that: they strip mass entertainment down to its bones. Heidecker’s best work is gives you a “seeing the Matrix” feeling. Few men have penetrated as deeply (or as funnily) into the corruption and emptiness of modern culture, and for that I deeply respect Heidecker.

…But then he started taking an interest in politics.

Little by little, it began to ruin his comedy. On Cinema swiftly devolved from a hilarious skewering of shitty podcasts to a legitimately angry political satire with Heidecker playing a cartoon version of Trump. His cleverness and self-awareness disappeared. Soon he was unironically participating in stuff like The Big Unfollow, a campaign to reduce Trump’s Twitter follower count.

In 2017 he released Too Dumb for Suicide, an album of Trump protest songs. They were written quickly in various times and places and moods (usually “with the blood still boiling from whatever indignity or absurdity had popped up on my newsfeed that day”, as Heidecker once wrote). Some are exhuberantly filthy, others sound like a captive lamenting in Babylon. In short, it listens like a Greek chorus of the anti-Trump left, capturing its gradually deflating mood.

The songs are decent pastiches of 70s dad-rock. “Mar-a-Lago” is based on Jimmy Buffett’s “Margaritaville”, with an easy, swinging cod-country rhythm. It contain’s the album’s most benign portrayal of Trump: a bumbling duffer manipulated by dark forces beyond his understanding when he really just wants to play golf. “Richard Spencer” is a Randy Newman ballad about punching people (sadly, not Randy Newman). “Imperial Bathroom” is a late 70s Elvis Costello song about Trump’s bowel movements, complete with nasal paint-thinner vocals and a blaring farfisa organ. Lyrically it’s not far removed from late 70s Costello, either.

Suicide is good more than great, and adequate more than good. While Heidecker knows how to write a tune, he’s not a dazzlingly brilliant songwriter. And though he can sing and play guitar, his performances usually just make you want to listen to whoever he’s parodying. His voice is highly limited, and the arrangements of several songs are bent like pretzels to accomodate his narrow range.

Many of these songs are as ephemeral as mayflies, dashed out in response to something happening on the news. They don’t have much juice in 2022, unless you want to Google obscure Trump scandals from half a decade ago (“hey, remember when he was trying to make his private pilot the head of the FAA?”).

Sometimes they backfire, and make Heidecker look pathetic. Or “For-Chan”, he takes aim at people who were mean to him on Twitter. “MAGA” just consists of nasty dehumanizing caricatures of stupid racist Trump voters. If you wrote a song like this about Obama supporters , there would be hell to pay. Maybe this was all hard-hitting satire in 2017. But now, a different picture emerges: Heidecker is a social media addict, doomscrolling Twitter like a junkie chasing the dragon, getting high on rage and misery.

Ironically, he’s getting played by the same cynical media he used to laugh at, and his comment about newsfeeds is revealing. The media wanted his blood to be boiling. They wanted him to think that Trump was America’s Hitler. How doesn’t he see that?

Although journalists individually may not like Trump, the media as an institution adores him. It only cares that you keep clicking and keep reading and keep getting angry, and Trump was crack cocaine. In Jul 2015, Huffington Post announced that they would only cover Trump’s candidacy in the Entertainment section, along with the Kardashians and the Bachelorette. “Our reason is simple: Trump’s campaign is a sideshow. We won’t take the bait.” One year later, the front page of their site had twenty-two Trump stories on it. Turns out they did take the bait. So did Heidecker.

And there’s still another side of Suicide, Too Dumb For: naked, unreconstructed fantasizing. “Sentencing Day”, for example, describes a universe where Trump is finally held accountable for his crimes.

The jury was 12 to none

The case was cut and dry

The only question remains is:

Will he live or die?

On one hand, the song’s kind of masturbatory: like a teenage girl writing fanfic where Harry kills Hermione and marries her OC self-insert.

On the other hand, it’s real. Heidecker is giving voice to authentic emotions here, and this is something you seldom saw in his work up until now. He’s not being vague. He’s not hiding inside a clever Kaufmanesque persona. He’s just being a person, saying what’s on his mind.

And then there’s “Trump Tower”, which was written (if I’m not mistaken) on the day of Trump’s inauguration.

“Well, they can take me down to the bowels of Trump Tower / And put me on the rack next to all of my brown and black brothers / And make me pledge allegiance to the hashtag MAGA, no other/ And rip my arms and legs off while I’m crying for my mother / But I’ll be hell-bent to call that motherfucker President.”

It sounds like a bit, but just listen to it. Heidecker sounds exhausted and sad and spiritually sick. He means every word. He did everything he could, and it wasn’t enough. The custard pie went splat, and Trump became President.

No Comments »

The first Helloween album is a classic of German power/speed metal. “Ride the Sky” in particular is one the most ripped-off songs ever. It was white-hot innovative in 1985 and still listens pretty well today.

On the back of albums like this, Germany was the dominant country for power metal through the 80s, 90s and 2000s. (In later decades it ceded space to Finland and Sweden, which is also when the genre stopped being worth listening to, for the most part). There’s a “Teutonic” PM style you can easily recognize: Judas Priest style songwriting with lots of 16th note picked-riffs, and “rough” vocals that are more enthusiastic than good. This regional style is highly distinctive: you can typically say “yep, this power metal band’s from Germany” a few seconds after the needle falls.

Kai Hansen and Michael Weikath go about 50-50 on the songwriting (most of the songs were written years earlier than 1985, for various proto-Helloween bands). Hansen’s efforts are stronger, probably because he has to sing them and better knows the limitations of his voice. “Ride the Sky” is an excellent opener, full of energy and riffs. (Also, is it the first known example of a power metal band rhyming fly with sky?) “Phantoms of Death” has wicked riffs and an excellent gang vocal chorus. It features a keyboard line, like a preview of the direction they’d take on their next album. Check out the Iron Savior cover, too. “Gorgar” (which was written in 1981) has a silly, humorous tone: Running Wild and Blind Guardian certainly weren’t writing songs about pinball boards at this point. Helloween’s lightness set them apart from other bands – they weren’t serious about what they did, which sometimes helped them and sometimes didn’t. They have a lot of nerve crediting the intro track to “Weikath/Hansen” when it’s just the melody of “London Bridge Is Falling Down”.

Weikath’s songs are good but are all the exact same tempo (“Reptile” excluded), making them a slightly repetitive. “Heavy Metal” is a Scanner kind of song, and “How Many Tears” is rampaging and furious epic, running a bit long at seven minutes. Hansen’s voice just doesn’t work here – he sounds ragged and out of breath in the climactic chorus. “Tears” more than any song demonstrated that the band needed to find a dedicated singer.

There’s a few different versions of Walls of Jericho hanging around. The original 1985 Noise LP is the definitive version. The 1987 CD edition has a bunch of extra songs, but it doesn’t listen as well: “Starlight” is worse than “Ride the Sky”, and “Judas” and “Murderer” have the exact same chorus (the songs are tracklisted at opposite sides of the CD, in the hopes you won’t notice!) I really love “Warrior”. Hansen is in total command here. “Silent falls the hammer!”

Production values? What are they? You hear reverb-drenched Marshalls and not much else. Whenever the songs get fast or busy, the music kind of flies to pieces in your auditory canal like a pinata, but that’s much-loved tradition of Teutonic PM too.

(It’s also a tradition to have questionable band names. Helloween got its name because, as Hansen explained once, “Halloween comes but once a year, but you can have Helloween every day“. It’s actually one of the better names Germany has to offer: other bands include Chinchilla, Edguy, Pink Cream 69, and…ugh…Custard.)

No Comments »