Most scams are only viable at a small scale. Strangers in Paris might fasten a “friendship bracelet” around a snatched wrist and then demand payment for it, but this trick can’t go beyond a few tourists losing tiny amounts of money. If it becomes too common – with Av des Champs-Élysées flooded with grifters offering bracelets – tourists will get smart and the grift won’t work. There will never be a billion dollar friendship bracelet industry.

There are only about three or four cons that work at scale (thank God). The most prevalent is the bagholder con: borrow money from some people, use their money to inflate your perceived value, borrow a larger amount of money from more people, and then use their money to repay the first.

This scales very well. In fact, it has to scale. The moment there are no new investors – when Paul wants his money back, and no Peter exists to rob – the scheme falls apart.

Ponzi schemes, pyramid schemes, MLM schemes, and stock market pump-and-dumps are riffs on this idea. Karl Marx identified capitalism itself as a bagholder con, requiring ever-increasing profits to support itself. Regardless of whether he was right, the con succeeds because it’s reminiscent of how real investment looks and works. “Today, you pay me x. Tomorrow, I pay you x(1+y).” This can be a healthy thing, rewarding risk-takers and people with vision. Done right, it is nothing less than fiduciary time travel, moving money from the future (where it’s useless) to the present (where it’s not).

“This thing will be worth lots of money tomorrow. If I just had enough cash to get it off the ground…”

But in bagholder cons, the thing is worth nothing. It’s a lemon. It will have no value tomorrow, next week, next year; it is pluperfectly worthless except as the life support system for a speculation bubble. Sometimes there is no “thing” at all, just a wind-filled space. Charles Ponzi’s 1920 scheme (which involved the arbitrate of postal coupons) was exposed because it was physically impossible for Ponzi to be doing what he said he was doing: he’d have needed to mail hundreds of millions of coupons, exceeding all legitimate mail in circulation many times over.

The winners in such schemes are typically people who invest early, have the value of their share pumped by gullible “bag holders”, and then pull their cash out before reality reasserts and the price crashes to the floor.

The losers are the people who get in late, or those don’t sell – those who think that the price crash is some moral test the have to pass.

Technically speaking, anyone who invests in anything is a loser. There’s no way around it. Money has gone from your pocket to someone else’s. You might expect to regain it later, but until that happens and you cash out successfully, you have lost 100% of your investment. This is similar to how any money added to a poker pot should be regarded as lost money – until you win, it’s gone. But gambling is universally seen as either a fun game or a harmful addiction, while investment (at final evaluation, gambling with a business degree) is regarded as responsible financial behavior. You’re building the future! Maybe your own. Maybe someone else’s.

It’s psychologically interesting to watch scammed people in action. Some are innocent naifs who were duped into believing a bad investment was a good one (Charles Ponzi’s scheme was a good example). Sometimes, they’re doubly duped: they think they’re getting in on a scam’s ground floor when the actual mark is them (most MLMs fit this pattern). David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con describes how surprisingly few victims of cons actually believe the con was a legitimate way of making money. Instead, most believed they were being invited to rip off someone else.

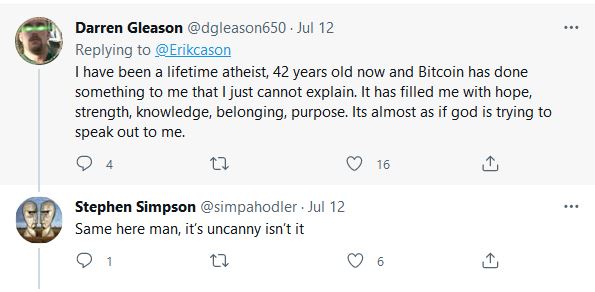

But in either case, the mastermind behind the con does not want anyone to sell. This deflates the bubble, and the bubble’s the only valuable part. So you see conversational patterns cultivated that can only be called cultlike. Unquestioning devotion. Denial of any possible failure. Criticism isn’t tolerated. Questions aren’t asked. Delusional “yeah, we’re all at a party together! WOOO!” styles of rhetoric. There’s a specific way they talk that you don’t see from normal people.

I am suspicious when I see this sort of thing. Hype is a bad signal. It almost looks as if the hype is the entire point, and there’s nothing underneath.

(“hodler” in the second user’s name is affectionate slang for “holding” onto your Bitcoin instead of selling as the price starts to fall.)

In most cases, people with investments have little reason to talk about their investments. If I had a pirate’s treasure map, the last thing I’d do would be to brag about how cool it is to go looking for treasure, or how digging on remote islands will change your life. This can only hurt me, by increasing the odds that the pirate treasure will be found before I get there.

But suppose I didn’t have a pirate’s treasure map. Suppose my income actually came from selling fake maps. Then I might talk about it a lot.

But are cryptocurrencies Ponzi schemes?

The question illustrates a weakness in language. You can say no or yes and be right. Is it literally a Ponzi scheme? No. There are superficial differences. Ponzi schemes are centralized, run by a single criminal, and involve direct transfers of “new money” to pay off old investors. Bitcoin does not have these features.

But if you’re asking “does it share every interesting trait with Ponzi schemes”, I think this is the case.

Every promise of cryptocurrency having real-world utility has thus far failed to materialize. It’s slow, wasteful, expensive, and volatile. Mistakes are permanently written onto an immutable ledger, lost money can’t be recovered, and most solutions (such as “smart contracts”) involve tying the cryptocurrency back to a regulatory body, defeating its purpose.

Various companies adopted Bitcoin in light of the first bubble. Most eventually dropped it, some with frank admissions that it was not suitable for anything except a bubble. Stripe:

Our hope was that Bitcoin could become a universal, decentralized substrate for online transactions and help our customers enable buyers in places that had less credit card penetration or use cases where credit card fees were prohibitive. Over the past year or two, as block size limits have been reached, Bitcoin has evolved to become better-suited to being an asset than being a means of exchange.

Proper investment moves money from the future into the present. Cryptocurrencies do the reverse: move money from the present into the future. Tons of people are still “hodling” as we speak, trying to parlay their savings into a profit in the eternal tomorrow. Because they’ve been told to do so, by people who do not have their interests at heart.

You’ll notice that most cryptocurrency hype focuses, not on things crypto is doing now, but on things that it could do in the future. As David Gerard says, “could” is a misspelling of “doesn’t.”

But this is where we see the main difference between cryptos and Ponzi schemes. They’re bad differences. They

Charles Ponzi was one man. When he ended up in prison. Bitcoin, for example, doesn’t. It’s

Likewise, Ponzi proposed a simple. This could be readily tested against reality, and when it failed, his credibility vanished.

But Bitcoin has no way to fail. One almost thinks it was designed to have no way to fail.

There is no real endpoint Bitcoin is pointed toward. There are several. Evangelists say it will

- Bank the unbanked

- Separate money from the state

- Create a unified world currency

- Protect the economy from crashes

- Enable individuals to transact outside of a legal framework

- etc

Some of these ideas make no sense, and some fight each other. But that’s not the point. This multi-goal argument allows cryptos to continue to seem like a good idea no matter how badly a given prediction fails. It’s a decentralized Ponzi scheme. It takes the bubble and welds nearly unbreakable metal around it, keeping the bagholders from selling.

Bitcoin is propositionally unfalsifiable. No matter how badly a given promise crashes and burns, there’s always going to be something else it could possibly do. You never have to look like an idiot for investing in Bitcoin. You do have to become an idiot, however.

No Comments »

(Previously published on Misery Tourism)

t minus 0. the rain is falling upward.

droplets glitter as they ascend from the ground, silver knives drawn from the earth’s exsanguinated carcass. they slash past your face in skeins and showers, barrage of negative barometric pressure, cold braille letters flayed into skin. the droplets whisper once and then vanish into the wind-filled voidmouth of the sky.

t minus 1. the clocks are running backward.

metal hands weave sinistrorse incantations, reeling rivers of time back into gear-toothed heartwork. each one a merciless creditor calling in debts of hours fwdslash minutes fwdslash seconds fwdslash planck lengths. they gave. now they want it all back.

t minus 2. an integer somewhere has flipped signs. the only explanation. positive into negative, forward gear into reverse, progress into regress, matter into fire, world into hell.

the past becomes an abyss, a terminal throat lined with blades. stumble. fall. plunge. see how deep the cuts go.

t minus 3. excruciating pressure grips your head. there are twelve bones in the human skull. you weren’t aware of just how far they’d slid and distorted over your lifetime. devastatingly, they try to return to their neonatal configuration. sensory circuits glitch and interrupt as bone shards saw through them like teeth.

t minus 4. you feel itching rivers of sweat crawl back into pores; yards of filthy hair sucked back into follicles; a sigmoid colon swelling grotesquely with impacted filth. chains of fat, protein, and carbohydrates recombine until there are dead animals floating sightlessly in your belly. cannot be endured. must be.

t minus 5. heat. nausea. ecstasy. shafts of pain driving holes in consciousness. you dimly perceive the outside world as it implodes, collapsing back into its own shadow. a flock of sparrows scythes against the sun. wrong direction. you see a gun. now an elaborate device for extracting bullets.

t minus 6. you are looking down a back alley, a playground from your early childhood, reconstructible in every detail from memory – cracked asphalt, graffiti tags; cigarette ends; broken glass, trickling drains, gutters choking on wet leaves, comforting filth.

but it’s changed. the details are all wrong. the gutters flow freely. the graffiti is gone. the name you scratched into a brick is missing, as though you’ve been struck from history by a censorious goskomizdat.

this is the alley as it existed at first construction: a painful mystery of poured concrete: perfect and inhuman, unsullied by time and by you. it breaks you. you remember and love this place. it insists you were never here.

t minus 7. you get out your phone, meaning to call a friend, call anyone. you need confirmation that you still exist.

the phone instantly deconstructs in your hand, becoming a shrapnel blast of its constituent parts. there was no phone. there was australian bauxite, american beryllium, and chinese yttrium, neodymium, and gallium. but no phone. you are a phone.

t minus 8. the breakdown is accelerating. time’s ladder shatters at your feet, rung by rung, the splinters driven bone-deep. memories force themselves free from the cracks in your head – spilling into the air, gaining corporeal weight and thickness until they merge with the experiences that made them.

the distant past speeds close. invasion of was. colonisation of used to. revanchism of the past tense. veni vidi vici. i went, i was seen, i was conquered. everything you ever ran from is coming back. every prison cell you ever walked free from has a door open to readmit you.

t minus 9. graveyards empty themselves – forgotten terrors are again worthy of fear, abandoned delusions again become true. the world is again ruled by fear of black mother kali, of hel, of thanatos, of sedna, of sekhmet, of phlogiston, of sneezing out your soul. geotrauma shakes the earth. mountains implode like useless wavefunctions, tectonic plates spar upon seas of magma. entire continents plunge out of sight, or recombine into unrecognizable ancient isomorphs. blink and you’re a citizen of gondwanaland. blink twice and you’re a citizen of pangea. at last, even these schemas break upon time’s wheel, leaving a perfect nothing. the air rends itself to shreds, revealing the glow of total shannonian enthalpy.

t minus 10. it’s indescribable. the eternal dawn refracts through your glasslike flesh, setting your bones afire. collapse before it. you have no legs. your eyes are useless ectopic platelets. can’t see tomorrow, can’t imagine tomorrow, can’t imagine imagining. all senses converge on a universal beginning – the past, rushing toward you.

the singularity, the original sin, the shattering wall of light from a plutonium bomb at ground zero. the nightmare starts here. irrelevant where it ends. terminal syzygetics cover the sky like stormclouds, admitting no hint of a future. everything you ever tried running away from is inside this single point, and so are you, at your weakest moment. blind. terrified. a statue writhing inside a block of marble. all escape routes are closed now. there is nowhere to go.

t minus ∞. you open your mouth. it swallows a scream.

No Comments »

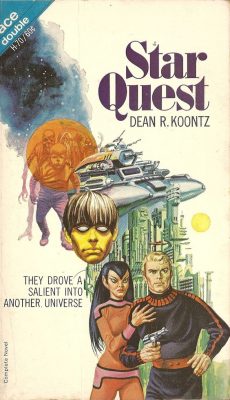

The Dean Koontz of 2022 has hair plugs and writes preachy stories about libertarian gun owners who fight supernatural strawmen for collectivism and/or postmodernism with the aid of guardian angels and/or pet dogs. The Dean Koontz of 1968 had no hair plugs and wrote Heinlein-style science-fiction.

Star Quest is his first book, if it can even be called that. It’s a 25,000 word novelette that was packaged as part of an “Ace Double”, along with Doom of the Green Planet by Emil Petaja. Ace Books told Dean that his side of the split was too short, and asked if he would accept $1250 so Petaja could get $1750. Years later, Petaja revealed that Ace Books had run the same line on him – he would get $1250 and Koontz $1750!

The story’s a military SF yarn. A sentient tank called Jumbo Ten (lol) is fighting a war for the despotic Romaghins against the invading Setessins when he suddenly he realises that he’s not a machine at all, and that his brain is from a human called Tohm (gross). This realization causes him to go AWOL mid-battle and begin searching for his missing past. Interesting, there’s a piece of Stephen King juvenilia (“I’ve Got to Get Away!”) with nearly the same basic plot.

To state the obvious, Star Quest was written quickly by a young man. It has problems typical of books written quickly by young men.

Laser cannon erupted like acid-stomached giants, belching forth corrosive froth that even the alloy hulls could not withstand for any appreciable length of time.

Why are the “laser cannon” belching “corrosive acid”? Many books fuck up their continuity, but usually not in the same sentence.

Koontz loves flowery literary passages, so our novel about a sentient tank called Jumbo Ten also has stuff like this:

But the Fates, those fickle ladies, will often change their minds and lend a hand to those they have so callously crushed before. His web of life had been spun by Clotho who immediately washed her hands of it and moved on to another loom. Lachesis, who measured the length of his strand, decided to fray it down slowly to whittle it to near nothingness. But now, just as Atropos was coming forth with her golden shears to snip it completely, Clotho had a change of heart. Perhaps, she was unemployed and restless that day, looking for something, anything to do. In any event, she stopped Atropos with a kind word and a cold stare, and began spinning again more thread…

Was “those fickle ladies” really the right phrase? Myself, I would have gone with “those goddamn broads.”

Ace Books did not use their stolen $500 to pay for copyediting, and the book contains even more spelling errors than this review. Jumbo Ten, we learn, is made of “alloyed steal”. I will allow that “He opened his corn-system” is probably an OCR error in the digital copy I found.

The story is fast paced and somewhat exciting. And it does have ideas, like a sci-fi invocation of the “multiverse” theory well before Heinlein wrote The Number of the Beast.

But Tohm/Jumbo Ten’s motivations are too stock to be interesting: he wants to go home, find his girlfriend, etc. These universal impulses are supposed to make him sympathetic, but they’re too universal: he loses his identity in a sea of other sci fi heroes who are characterised in exactly the same way. He might be convinced he’s a living person, but he does not convince the reader.

In 1968, it would have been the literary version of fast food: made cheaply and consumed quickly. But now, it’s something more: an interesting curio from a very famous writer’s past. Authors only get one first novel, and it’s fascinating that this was Koontz’s. Themes of individualism are the only thing bridging his work from then to now. Otherwise, this is a totally different writer, and a reminder that (despite arguments otherwise), we fundamentally aren’t the person we were yesterday, and also not the person we will be tomorrow.

No Comments »