(Previously published on Misery Tourism)

t minus 0. the rain is falling upward.

droplets glitter as they ascend from the ground, silver knives drawn from the earth’s exsanguinated carcass. they slash past your face in skeins and showers, barrage of negative barometric pressure, cold braille letters flayed into skin. the droplets whisper once and then vanish into the wind-filled voidmouth of the sky.

t minus 1. the clocks are running backward.

metal hands weave sinistrorse incantations, reeling rivers of time back into gear-toothed heartwork. each one a merciless creditor calling in debts of hours fwdslash minutes fwdslash seconds fwdslash planck lengths. they gave. now they want it all back.

t minus 2. an integer somewhere has flipped signs. the only explanation. positive into negative, forward gear into reverse, progress into regress, matter into fire, world into hell.

the past becomes an abyss, a terminal throat lined with blades. stumble. fall. plunge. see how deep the cuts go.

t minus 3. excruciating pressure grips your head. there are twelve bones in the human skull. you weren’t aware of just how far they’d slid and distorted over your lifetime. devastatingly, they try to return to their neonatal configuration. sensory circuits glitch and interrupt as bone shards saw through them like teeth.

t minus 4. you feel itching rivers of sweat crawl back into pores; yards of filthy hair sucked back into follicles; a sigmoid colon swelling grotesquely with impacted filth. chains of fat, protein, and carbohydrates recombine until there are dead animals floating sightlessly in your belly. cannot be endured. must be.

t minus 5. heat. nausea. ecstasy. shafts of pain driving holes in consciousness. you dimly perceive the outside world as it implodes, collapsing back into its own shadow. a flock of sparrows scythes against the sun. wrong direction. you see a gun. now an elaborate device for extracting bullets.

t minus 6. you are looking down a back alley, a playground from your early childhood, reconstructible in every detail from memory – cracked asphalt, graffiti tags; cigarette ends; broken glass, trickling drains, gutters choking on wet leaves, comforting filth.

but it’s changed. the details are all wrong. the gutters flow freely. the graffiti is gone. the name you scratched into a brick is missing, as though you’ve been struck from history by a censorious goskomizdat.

this is the alley as it existed at first construction: a painful mystery of poured concrete: perfect and inhuman, unsullied by time and by you. it breaks you. you remember and love this place. it insists you were never here.

t minus 7. you get out your phone, meaning to call a friend, call anyone. you need confirmation that you still exist.

the phone instantly deconstructs in your hand, becoming a shrapnel blast of its constituent parts. there was no phone. there was australian bauxite, american beryllium, and chinese yttrium, neodymium, and gallium. but no phone. you are a phone.

t minus 8. the breakdown is accelerating. time’s ladder shatters at your feet, rung by rung, the splinters driven bone-deep. memories force themselves free from the cracks in your head – spilling into the air, gaining corporeal weight and thickness until they merge with the experiences that made them.

the distant past speeds close. invasion of was. colonisation of used to. revanchism of the past tense. veni vidi vici. i went, i was seen, i was conquered. everything you ever ran from is coming back. every prison cell you ever walked free from has a door open to readmit you.

t minus 9. graveyards empty themselves – forgotten terrors are again worthy of fear, abandoned delusions again become true. the world is again ruled by fear of black mother kali, of hel, of thanatos, of sedna, of sekhmet, of phlogiston, of sneezing out your soul. geotrauma shakes the earth. mountains implode like useless wavefunctions, tectonic plates spar upon seas of magma. entire continents plunge out of sight, or recombine into unrecognizable ancient isomorphs. blink and you’re a citizen of gondwanaland. blink twice and you’re a citizen of pangea. at last, even these schemas break upon time’s wheel, leaving a perfect nothing. the air rends itself to shreds, revealing the glow of total shannonian enthalpy.

t minus 10. it’s indescribable. the eternal dawn refracts through your glasslike flesh, setting your bones afire. collapse before it. you have no legs. your eyes are useless ectopic platelets. can’t see tomorrow, can’t imagine tomorrow, can’t imagine imagining. all senses converge on a universal beginning – the past, rushing toward you.

the singularity, the original sin, the shattering wall of light from a plutonium bomb at ground zero. the nightmare starts here. irrelevant where it ends. terminal syzygetics cover the sky like stormclouds, admitting no hint of a future. everything you ever tried running away from is inside this single point, and so are you, at your weakest moment. blind. terrified. a statue writhing inside a block of marble. all escape routes are closed now. there is nowhere to go.

t minus ∞. you open your mouth. it swallows a scream.

No Comments »

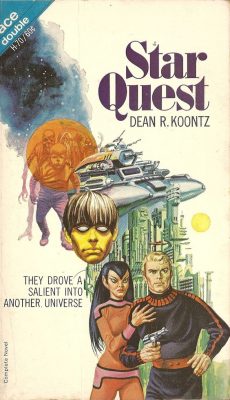

The Dean Koontz of 2022 has hair plugs and writes preachy stories about libertarian gun owners who fight supernatural strawmen for collectivism and/or postmodernism with the aid of guardian angels and/or pet dogs. The Dean Koontz of 1968 had no hair plugs and wrote Heinlein-style science-fiction.

Star Quest is his first book, if it can even be called that. It’s a 25,000 word novelette that was packaged as part of an “Ace Double”, along with Doom of the Green Planet by Emil Petaja. Ace Books told Dean that his side of the split was too short, and asked if he would accept $1250 so Petaja could get $1750. Years later, Petaja revealed that Ace Books had run the same line on him – he would get $1250 and Koontz $1750!

The story’s a military SF yarn. A sentient tank called Jumbo Ten (lol) is fighting a war for the despotic Romaghins against the invading Setessins when he suddenly he realises that he’s not a machine at all, and that his brain is from a human called Tohm (gross). This realization causes him to go AWOL mid-battle and begin searching for his missing past. Interesting, there’s a piece of Stephen King juvenilia (“I’ve Got to Get Away!”) with nearly the same basic plot.

To state the obvious, Star Quest was written quickly by a young man. It has problems typical of books written quickly by young men.

Laser cannon erupted like acid-stomached giants, belching forth corrosive froth that even the alloy hulls could not withstand for any appreciable length of time.

Why are the “laser cannon” belching “corrosive acid”? Many books fuck up their continuity, but usually not in the same sentence.

Koontz loves flowery literary passages, so our novel about a sentient tank called Jumbo Ten also has stuff like this:

But the Fates, those fickle ladies, will often change their minds and lend a hand to those they have so callously crushed before. His web of life had been spun by Clotho who immediately washed her hands of it and moved on to another loom. Lachesis, who measured the length of his strand, decided to fray it down slowly to whittle it to near nothingness. But now, just as Atropos was coming forth with her golden shears to snip it completely, Clotho had a change of heart. Perhaps, she was unemployed and restless that day, looking for something, anything to do. In any event, she stopped Atropos with a kind word and a cold stare, and began spinning again more thread…

Was “those fickle ladies” really the right phrase? Myself, I would have gone with “those goddamn broads.”

Ace Books did not use their stolen $500 to pay for copyediting, and the book contains even more spelling errors than this review. Jumbo Ten, we learn, is made of “alloyed steal”. I will allow that “He opened his corn-system” is probably an OCR error in the digital copy I found.

The story is fast paced and somewhat exciting. And it does have ideas, like a sci-fi invocation of the “multiverse” theory well before Heinlein wrote The Number of the Beast.

But Tohm/Jumbo Ten’s motivations are too stock to be interesting: he wants to go home, find his girlfriend, etc. These universal impulses are supposed to make him sympathetic, but they’re too universal: he loses his identity in a sea of other sci fi heroes who are characterised in exactly the same way. He might be convinced he’s a living person, but he does not convince the reader.

In 1968, it would have been the literary version of fast food: made cheaply and consumed quickly. But now, it’s something more: an interesting curio from a very famous writer’s past. Authors only get one first novel, and it’s fascinating that this was Koontz’s. Themes of individualism are the only thing bridging his work from then to now. Otherwise, this is a totally different writer, and a reminder that (despite arguments otherwise), we fundamentally aren’t the person we were yesterday, and also not the person we will be tomorrow.

No Comments »

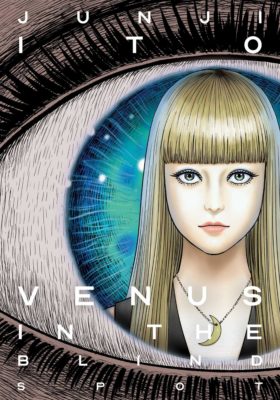

A collection of shorts from everyone’s favorite dentist, Junji Ito.

It’s an English release of The Best of Junji Ito, which was collected in 2019 by Shogakukan Big Comics Special. It’s the same basic idea as Metallica’s Garage Days Re-Revisited – odds and ends that don’t fit anywhere. Four stories are bonuses from Gyo, Remina, and Black Paradox. Three are adaptations of prose works from Edogawa Rampo and Robert Hitchens. The rest is previously uncollected material. It’s not clear why these particular stories were chosen, or why others (such as “Mystery Pavilion”, “Phantom Mansion”, etc) were missed.

Some highlights:

“Billions Alone” – 2004 Junji Ito stares into a crystal ball and perfectly predicts the world of 2022. People are forced into isolation by a sinister force that kills them when they gather together. You’ll think of COVID19, of course, but the corpses-stitched-together visual could be an equally good comment on social media, which erupted like a cancer years after the story’s release. Spot the panel that inspired The Human Centipede.

“Venus in the Blind Spot” – a sweet, weird story about a girl who vanishes from your visual field when she gets close. It’s a Tomie story with less gore, reprising Ito’s usual themes of madness, desire, female beauty, and perception. It would be a good introduction to his work.

“The Enigma of Amigara Fault” – chilling story that makes my skin try to crawl off my skeleton, even now. A landslide reveals human-shaped holes in a mountain, which some people try to enter. A really effective and sharp story body horror and claustrophobia. Overall, Uzumaki is Ito’s greatest manga, but if you want to sharpen his entire career down to a thirty page highlight, this is it.

“The Sad Tale of the Principal Post” – a man gets trapped underneath a pillar upholding his house. Nobody online seems to understand the story, but it isn’t that confusing. It just takes a common metaphor (a father supports his house!) and makes it literal. More a joke than a story.

“The Human Chair” – Rampo’s 1925 story (about a carpenter who installs himself in a hidden compartment in a chair so that he can feel women sitting on him) is a classic of Japanese horror. To experience this much voyeuristic sexual perversity you’d have to be a girl riding the Shinkansen. Although it shares a title with this classic tale, Ito’s story is more of a sequel, continuing and expanding the plot.

“Master Umezz and Me” – a very personal story where Ito discusses his fannish obsession with Kazuo Umezu, the godfather of Japanese horror manga. Umezu (who, by the way, is 85 years old and announced the launch of a new series this year) is so different from Ito that it’s always surprised me that he drew inspiraiton from him. Aside from some vague surface similarities (“supernatural immortal girl” = Orochi/Tomie, “kids surviving in a hostile wasteland” = The Drifting Classroom/Uzumaki vol 3, Bible-style apocalypse where mankind is punished = Fourteen/Remina) their work is nothing alike. The story’s a heartfelt and affectionate tribute. Sometimes we forget what it’s like to be a kid who enjoys something: it’s a pure, heliumlike joy seldom recaptured in adulthood.

Parenthetically, does Goodreads sell a licensed crack pipe that you’re supposed to light up before writing reviews?

“Viz Media’s blurb for Venus in the Blind Spot is really weird: it claims this is a “best of” collection of Junji Ito’s stories but, as far as I can tell, only one – maybe two – stories have previously appeared in print before: The Enigma of Amigara Fault and The Sad Tale of the Principal Post possibly both appeared in Dissolving Classroom. So this is a “best of” collection that features almost all-new stories!?”

Ito should make a manga about this person’s mind. It’d be his scariest work by far.

No Comments »