The German language has two words for silence. Stille means there is silence. Schweigen means something is silent. The change of meaning is subtle yet important: schweigen suggests that the silence isn’t incidental: something could make a sound but isn’t. Put another way, stille is meaningless silence, schweigen is meaningful silence.

English lacks this distinction and must modify “silence” into an adverb (see “keep silent” and “remain silent”) to achieve the same nuance. When encountering “silence” in an English translation of German verse I sometimes wonder whether the German contained stille or schweigen.

Purity! Purity! Where are the terrible paths of death,

Of grey stony silence, the rocks of the night

And the peaceless shadows? Radiant sun-abyss.

Sister, when I found you at the lonely clearing

Of the forest, and it was midday and the silence of the animal great;

Whiteness under wild oak, and the thorn bloomed silver.

Enormous dying and the singing flame in the heart.

Darker the waters flow around the beautiful play of fishes.

Hour of mourning, silent vision of the sun;

The soul is a strange shape on earth. Spiritually blueness

Dusks over the pruned forest; and a dark bell rings

Long in the village; peaceful escort.

Silently the myrtle blooms over the white eyelids of the dead one.

Quietly the waters sound in the sinking afternoon

And the wilderness on the bank greens more darkly; joy in the rosy wind;

The brother’s soft song by the evening hill.

Georg Trakl (3 February 1887 – 3 November 1914) loved silence, particularly schweigen. The theme of quietness – deliberate quietness – makes his poems pulse and glow. “Springtime of the Soul” (Frühling der Seele) has three “silences”. The first and second (the animal, and the sun) are schweigen. To Trakl everything can conceivably have a voice. The third silence (the myrtle) is stille, which is actually unusual for Trakl – he often uses schweigen in reference to plants, too. He revered nature, and seemed to view it without the distinctions (sapient/stupid, ambulatory/stationary, alive/dead) that others imposed. To Trakl, it’s easy to imagine a plant talking, or the sun talking. His poems describe nature’s myriad forms as the folds and nodules of a single great throat, pouring out sound or silence.

Trakl died young after living a terrible life. His poems are fragile and often hurtful to read: they actually seem bruised, like flower petals crushed by the pressure of a thumb.

Something about his brain was abnormal. Dr Hans Asperger analyzed Trakl’s writings and declared him an exemplary case of the recently-discovered syndrome which bears his name. Trakl’s poems reflect a very intense relationship with topic matter: read a few Trakl poems and you’ll see him repeating ideas and subjects obsessively – trees, plants, pastoral settings, animals in forest glades, his sister (giving rise to unfortunate rumors about an incestual relationship between the two) – which is a hallmark of autistic “special interests”.

The sensoriality of Trakl’s poems is also remarkable, the way everything is chained to a description of a color or sound. In the above poem you can see how he keeps coloring things that don’t have color – eg, souls are blue, the wind is rosy. It’s possible he had synaesthesia, and experienced the world in a sensorally conjoined way that others didn’t.

Either way, there’s a childlike quality to his verse – in a positive sense. It uses simple words and simple ideas, but they hit hard, particularly the oblique yet awful passages alluding to war. Whenever man-made sound intrudes into a Trakl poem, it’s never good. “Trumpets” is short but memorable: reaching thunderstorm-like intensity that nearly equals Poe’s “The Bells”.

Under the trimmed willows, where brown children are playing

And leaves tumbling, the trumpets blow. A quaking of cemeteries.

Banners of scarlet rattle through a sadness of maple trees,

Riders along rye-fields, empty mills. Or shepherds sing during the night, and stags step delicately

Into the circle of their fire, the grove’s sorrow immensely old,

Dancing, they loom up from one black wall;

Banners of scarlet, laughter, insanity, trumpets.

Trakl’s work is easy to memorize, particularly upon repeated readings – which you’ll have to do, because his collected work is scant. Like the modernists and romantics he took inspiration from (Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine), he died long before his time. In World War I, he served as a medical officer, and had scant opportunity to experience either stille or schweigen. After the Battle of Grodek in 1914, he was given a barn full of ninety badly wounded soldiers, and told to care for them. He couldn’t cope, tried to shoot himself. For this he was sent to a military hospital in Cracow. He assumed he was going there as a medical officer. Instead, it as a convalescent. What’s that old joke about how doctors wear lab coats so you can distinguish them from their patients?

Whatever treatment he received didn’t work: his depression was deep and total. Eventually, he tried to kill himself a second time – this time with a cocaine overdose – and was successful. Another man consumed by mechanical violence. There’s something cruelly arbitrary about Trakl’s death – the Great War caused a lot of fathers to bury their sons, but at least most of the deaths have a kind of planned badness – a general decided it was worth the lives of x many soldiers for y tactical salient, or whatever. Trakl didn’t even get the dubious honor of being cannon fodder. His death was completely and finally meaningless – just a cruel incidental byproduct, serving no purpose except to return schweigen to his sound and image filled head. The war robbed a man of his life and the world of the poems he could have written. Here’s one last -“Grodek”.

At evening the woods of autumn are full of the sound

Of the weapons of death, golden fields

And blue lakes, over which the darkening sun

Rolls down; night gathers in

Dying recruits, the animal cries

Of their burst mouths.

Yet a red cloud, in which a furious god,

The spilled blood itself, has its home, silently

Gathers, a moonlike coolness in the willow bottoms;

All the roads spread out into the black mold.

Under the gold branches of the night and stars

The sister’s shadow falters through the diminishing grove,

To greet the ghosts of the heroes, bleeding heads;

And from the reeds the sound of the dark flutes of autumn rises.

O prouder grief! you bronze altars,

The hot flame of the spirit is fed today by a more monstrous pain,

The unborn grandchildren.

No Comments »

The post office is useless. They won’t mail ANY of my letters. They’re all like “please address them correctly” and “please include a stamp” and “please take the bombs out”. Christ. I don’t expect MENSA-level logic skills from the post office but what’s the point of sending letter bombs that don’t have bombs, you idiots?

End topic, start of new topic. “Waterboarding at Guantanamo Bay” sounds fun to a child but scary to an adult. Conversely, “the doctor will take your pulse” sounds innocuous to an adult but terrifying to a child. “T…take my pulse? Will I get it back?” As adults, we know what this means: the doctor is hungry and needs a starchy, calorie-filled legume such as a bean or a peanut to sustain his labors. Just one. Sometimes one is all it takes.

End/start. Once it was accepted wisdom in psychology that having a little of something brings you more happiness than having a lot (but not all) of the same something. Put another way, having a single slice of pie will make you happier than having an entire pie with a single missing slice.

This is based on findings from a study of Olympic athletes. Although the gold medalist the happiest man on the podium, the bronze medalist is happier than the silver medalist. It’s easy to speculate why. The bronze medalist is just glad that they medaled, while the silver medalist is stewing over how they barely missed the gold.

I read the study and it disappointed me. I doubt it will survive the replication crisis. They didn’t have any way of measuring athlete happiness, they had evaluators watch videos of athletes standing on a podium, and asked them to rate the happiness on their faces. How could this generate valid results? Some athletes are from countries with a cultural norm against smiling, other athletes are plastering fake smiles on their faces so they don’t get executed by firing squad back in Allfuckedupistan, there’s no way you can control for all the variables, how do we know people can accurately judge happiness by looking at videos, and so on.

It might not be true that bronze medalists are happier. But maybe it’s true that the public perceives bronze medalists as being happier, regardless of whether they actually are.

Could this be a good way of judging a person’s happiness? Obviously a single person’s estimation of another’s happiness will likely be wrong, but if you averaged the estimates of a hundred people who have just seen someone experience indeniably joyous event (such as seeing the number 6 and 9 appear on their grocery bill)…how accurately will this match the happy person’s own assessment of their mental state?

Could it actually be more accurate? Do other people know us better than we know ourselves?

It’s not impossible. Happiness is an emotional state with a biological basis (serotonin, and so on). But we can never directly report on this emotional state – we only have access to a memory of said state – even if that memory is only half a second old. And memories are notoriously inaccurate. Maybe I’ll remember a time as being happy it was actually sad. A larger population pool will remove this source of bias.

It’s not unreasonable that a crowd would understand an athlete’s emotions as well or better than the athlete themselves. The athlete is probably in a state of shock, vaguely aware of chemicals rushing through their body and not much else. Only later can they look back on the moment, replay the memory in their mind’s eye, and feel the happiness that in media res denied them. Perhaps they won’t feel happy at all – it was a hollow victory. I never talk about this but I won a gold medal once. No, I’m sorry. Bought. I bought a gold medal. It was at a store. It melted and went sticky. I’m reluctant to question the wisdom of the Olympics committee, and I know they have to cut costs, but why do they fill the insides of those things with chocolate?

In 1936, John Maynard Keynes wrote about a competition in which…

the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one’s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be.

This competition was the stock market.

The stock market is a beauty contest where you don’t pick the prettiest woman. Instead, you pick the woman the other judges think is the prettiest woman. “Well, I really like contestant #6, but nobody else will go for her. Contestant #9 is a more classic beauty.”

You’re judging the judgement of the prettiest woman. Except you’re not even really doing that, you’re judging the judgement of the judgment of the prettiest woman. And so on, ad nauseam. It’s not about the woman. It’s not even about the men. It’s about the system. A system that sprawls and grows the more its utilized, additional feedback back-propagating in, requiring additional epicycles. You have to find the Schelling point. The magic area of stability. But once people know where the Schelling point is, it disappears and reappears somewhere else.

In the stock market, it is of no intrinsic value that an investment is sound. Everything depends on the opinion of other buyers, who in turn are watching the opinion of still others. This is how a “pump” happens. Some people think a stock’s going to the moon, they plow money into it, the buying is interpreted by other people as a sign of success, and so on. The stock ends up valued far higher than it’s worth (infinitely higher, if the stock is worth zero), but then it implodes back to the X intercept and you end up typing incoherent rationalizations on a forum while misspelling the world “hold”.

Maybe this is why some people like Marxism, which (by way of Adam Smith) escapes the whole game by asserting that value is an objective quantity. The price of a commodity, to a classical Marxist, is determined by the amount of labor that went into it.

This provides the theoretical bulwarks for large chunks of Marxist thought, such as exploitation. If a pair of shoes is worth the labor that goes into making them, how does the boss of the shoe factory have profit left for himself after paying his workers? The answer, to Karl Marx, is that the boss is ripping off his workers. Underpaying them.

I don’t think that’s right, though. Labor affects the value of a commodity, but so do other things.

For example, which would you prefer: a dollar today, or a dollar tomorrow? Obviously, a dollar today. You can invest it and by tomorrow it will be worth more than a dollar. Money now is worth more than money later, and money yesterday is worth more than money now. The temporality of money changes its value.

And which would you prefer: a dollar in a Swiss bank account, or a dollar lying in plain view at Central Station, NY? The dollar in the bank account, because it’s far less likely to be stolen. The security of money changes its value.

When would you prefer to have a dollar: when your rent is short by $1, or when you’ve just won the lottery? Obviously the former. The amount of money you already have changes how much you value additional money.

I don’t know if Marxists consider money to be a commodity (probably not), but the logic above applies to any sort of valuable thing – shoes, food, etc. It seems that value is subjective. The Labor Theory of Value is about as sensible as an Atomic Theory of Value that proposes items be priced by their number of hydrogen atoms. Yes, atoms are an important part of items, as is labor. But that’s not all there is to know about them. Nor is it a sane bridge to establishing a Schelling Point such as price.

Value can appear out of nowhere at any time. So can entire concepts and worlds. A question: when did oil first appear? A few hundred million years back, when some dinosaurs died or something?

No. Or yes. But no.

In a real sense, oil was created in 1872, when the internal combustion engine was invented. Yes, it existed before, but it wasn’t oil. It was something else. It was worthless sludge that seeped and bubbled out of the ground. It had no intrinsic value, until suddenly it did in 1872, thanks to human ingenuity. (I’m smoothing off some historical rough edges, ie the ancient Chinese apparently made some use of petroleum.).

We redefined a waste product into the most valuable commodity in the world, and it wasn’t even that difficult. It might happen again. Knowledge without theory is just a pile of facts. Light. Noise. Waves. Amplitude. The air around us creaks and sunders before the weight of information pouring across its manifolds. What schemas will we uncover next?

End paragraph. I like the way keyboards work. When I run out of steam or say something embarrassing, I can just hit ENTER and it’s like I’m free from the past, free to make better choices. At any point I can scythe an unproductive topic remorselessly and start afresh with a new better one. Such as this one. I like you, new topic. You won’t let me down. I’m also stroking my scythe.

No Comments »

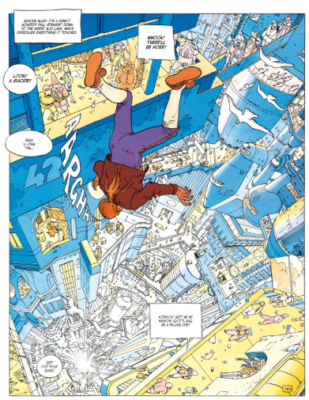

The greatest comic of all time, according to some. This is a small exaggeration. After exhausting, grueling, and – dare I say it – faintly erotic analysis, I bring you the truth. It’s the greatest comic of its first week of issuance in 1980. Perhaps the weekend after, too. Best I can do.

The story is complete rubbish: The Incal has a “toddler smashing action figures together” plot where the MetaBaron battles the HitlerRodents while the GlorpFucks unite the PlotStone with the QuantumMatrix and all seems lost but then the SlamPig Brigade arrives and blows up the NightmareBot and on and on and on (and on and on). Comics like The Incal don’t “end”, they merely stop having new issues produced. The fact that it has six volumes is incidental: it could just as easily have gone on for six more, or sixty more, or until Jodorowsky died.

People describe it as “surrealist” but it’s not, they describe it as “philosophical” but it’s not, etc. Visually it evokes those psychedelic 70s-80s animated movies like Wizards and Fantastic Planet, as well as French “bandes dessinées” comics such as Tintin. It consists of very powerful and imaginative imagery, with the plot noisily emitting a dense cloud of complications. It also reminds of Metal Hurlant/Heavy Metal – which it has to, because its artist Mœbius was an important figure in that comic. Some of Mœbius’s famous visual motifs are present in the Incal, such as Arzach’s white pterodactyl, here seen as the hero’s comical sidekick, Deepo.

Arzach is a fearsome beast, and I would recommend it over this comic. It’s short and confusing, but you feel in your bones what it’s trying to do. It stuns and awes the senses with visuals of alien worlds, making characters seen both big and small, and reading it is like drunkenly climbing a ladder to heaven. The absurd visual style (merging prehistory and the far-future) only adds to the grand, hallucinatory effect.

As does the fact that it’s wordless. Some comics gain from having text, others lose. Neil Gaiman once wrote that he “read” some Metal Hurlant comics (not understanding French) and loved them. Later, he read those same stories in English translation and was disappointed – now that he could understand the words, they seemed curiously small. I had a similar experience with certain untranslated Junji Ito manga. It wasn’t that they were bad, but my imagination made them seem much greater than they really were.

The Incal is probably a similar case: more enjoyable if you can’t read the words and only have Moebius’s imagery to guide you. The comic book emerged out of Jodorowsky’s 1975 attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune. He’d planned a 10-hour opus that would have made Heaven’s Gate look like a poster child for minimalism, featuring HR Giger, Mick Jagger, Salvadore Dali, spiritual and psychedelic themes, etc. He was unable to secure funding for this project (film studios have found more convenient ways to declare Chapter 11 bankruptcy) and much of the work he did was repurposed into The Incal. There’s little evidence of Dune in the final comic, but I doubt Jodorowsky’s planned film would have had much connection to it either.

There’s some cool moments. The in-media-res opening image of sleazy detective John DiFool being flung down “Suicide Alley” is striking and often imitated. The grungy tone of some of the urban scenes might have been an influence on eg, Blade Runner, just as the skulking bounty hunter MetaBaron reads as an early version of Star Wars’ Boba Fett (Fett’s first public appearance predates MetaBaron’s, but I’m fairly sure MetaBaron was conceived of earlier). There’s no shortage of ideas here, some you’ll recognize in later, more famous products. I have no idea to what extent this is conscious “inspiration”. Perhaps Jodorowsky merely put his hands on some ideas that were already circulating in science fiction and gave them form. Most pertinently: the world of The Incal feels slimy and lived-in, the politicians are corrupt, religious figures are hypocritical, everyone’s sex-obsessed and venal. It depicts a lived-in future, perhaps a died-in future. But spiritual purity is possible, no matter how debased you are.

The Incal definitely has flaws, but it also has strengths. It’s a highly charming work, always easy to like. It has a sense of humor – the pangender “Emperoress” got a laugh out of me. Fans of Jodorowsky’s films will probably love this, as it’s full of little echoes of El Topo and The Holy Mountain (the absurdity of Deepo becoming a religious icon is straight out of the latter movie).

But ultimately, it’s just not as clever as it wants to be. It needs writing to match Moebius’s art – either that, or no writing at all. The plot’s just standard science fiction and fantasy stuff that was done better before (and certainly better afterward), and although it’s more intense than the average Bronze Age superhero comic, but still hews to the superhero formula. The story is written to be both collapsible and extendable. It’s made up of details, none of which are essential. If you have too many pages, Trim some details. Conversely, you can extend a story by adding extra details. It’s always apparent that “story” is just a secondary concern to most comics. Their first one is to take up space. Their allegiance is to the space. They have to fill up a certain amount of page area and no more, and this locks them into place like iron bars. Nobody wants to pay for a comic with a blank page. Or half a blank page. Nor will they pay for a comic that ends mid-climax with “sorry, ran out of space! Send me a letter if you want to know the ending!” The story must fit. You’d think that the advent of webcomics would cause artists to break free of these limitations, but most don’t.

No Comments »