Let’s read a book together: Faucault’s histoire de la folie à l’âge classique:

“A book is produced. […] its doubles begin to swarm. Around it and far from it; each reading gives it an impalpable and unique body for an instant; fragments of itself are circulating and are made to stand in for it, are taken to almost entirely contain it, and sometimes serve as a refuge for it; it is doubled with commentaries, those other discourses in which it should finally appear as it is, confessing what it had refused to say, freeing itself from what it had so loudly pretended to be.

(Foucault, cited in Eribon 1991: 124)

…But we aren’t reading “a” book. We’re not reading the same thing and participating in a shared experience. We’re reading two different things: even though the above text might have all the same letters and words.

The thing is, they’re not being read by the same person.

Byron wrote Don Juan in 1819. It had a complicated publication history. Due to concerns over blasphemy and libel the book was released in two editions – a very expensive bound edition without an author’s name, and a very cheap bootleg that was distributed among anarchists.

From an evolutionary perspective this is r/K selection. An author wants his work to survive. They can do this by a) making their work so valuable and precious that it can’t be thrown away b) making it so cheap that it CAN be thrown away (and ends up becoming landfill, outlasting civilisation). Byron seems to have tried both strategies at once.

Were both editions the same book? I’d argue they’re not: the first edition was read by the upper class, and the second by anarchists. The first would have been read in a spirit of transgression: you were doing something naughty and beneath your station. A rich person reading Don Juan is like a rich person picking their nose at the dinner table. An anarchist would have read Don Juan as brutal, well-deserved skewering of Romantic literary conceits: one spark dancing in the all-consuming fire immanentizing the eschaton et cetera next paragraph

I sometimes wonder if there’s any point in writing anything. Any idea more complicated than “I exist” is going to be get misinterpreted by someone, somewhere. Readers are like distorted mirrors: light pours into them and is reflected, corrupted. Although from their perspective, it’s being reflected correctly. No other interpretation is valid except the reader’s. Don Juan is an anarchist anthem. Or it’s a toy for the enemies of the anarchists. It’s somehow both, and neither. It’s intended meaning was probably something else entirely.

Books tend to be used for propaganda. In the antebellum south, slave owners frequently justified using verses from the Bible. But freed slaves also relied on scripture, particularly the slave-freeing narrative of Exodus. “The Bible says” is often a less honest version of “I say”.

But a more fundamental issue is that words are a representation of a message, but not a complete representation. Sentences lack the context present in the author’s mind. The reader has to supply their own context, and they usually attribute the one they personally prefer.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

- She said she did not take his money.

This is the infamous “eight sentences in one”, where the meaning shifts depending on which word carries the emphasis. Additional permutations can be generated by emphasising multiple words (eg, She said she did not take his money.) None are correct. There’s additional pieces of context (who’s “she”?) that would further modify how the sentence is read.

This suggest that it’s a waste of time to hone and shape your writing. The point is to find the right audience, a group of people who are already attuned to your intended meaning. Early screenings of This is Spinal Tap were reportedly filled with squares who didn’t get the joke, and who thought that Spinal Tap was a real band. Rob Reiner and Christopher Guest clearly thought that the audience would be full of smart people like them, the idiots. The space of the human mind is pretty broad, and it can be hard to accept that you don’t occupy a prestiged position within it.

Have you ever wondered why Nigerian scam emails are always so…obvious? Why don’t they vary their pitch a little – by claiming to be from Senegal, say? This is actually intentional: they’re supposed to be obvious, because they only want gullible people to respond to their emails. Sending out millions of spam emails is the easy part: the hard part is finessing the repliers. You don’t want to spend three weeks talking to a person, only for them to decide you’re ripping them off. If you’re smart enough to notice that all scam emails are from the same country, you’re smart enough to not give a credit card number to a stranger. The scammers have found a way to filter their readers so that only the very, very stupid respond.

I think a true writer would use a similar technique. Somewhere out there is a person who thinks my unintelligible drooling makes sense. The challenge for me is to find that person. If it’s you: hello. Please never leave. You’re all I have.

It might be easier to create a perfect reader than a perfect book. I imagine a sociopath writer by crippling the brains of his reader so that they’re exactly that. It’s lucky that writers seldom become totalitarian dictators. Don’t think that Will Self’s new book is excellent? With the right cocktail of drugs you will. With the right frontal lobe excised, you will. You need the correct motivation. It will be fun.

No Comments »

An 18th century German composer who wrote the theme for a king, with a principle melody that ascends yet remains trapped in tonal space. A 19th century Dutch artist who created maddening and hallucinatory artwork, defying intuition about perspective and reality. A 20th century German mathematician who described the limitations of a formal system addressing itself.

According to this book, Godel, Escher, and Bach were three blind men touching the same elephant: the Strange Loop.

“The “Strange Loop” phenomenon occurs whenever, by moving upwards (or downwards) through levels of some hierarchial system, we unexpectedly find ourselves right back where we started.”

You get on an elevator on floor 1, go up nine floors, emerge on floor 10, and then take the stairs back down. This is a loop. But imagine taking the elevator from floor 1 to floor 10, and the door slides open to reveal…floor 1. This is a strange loop.

“But things like that don’t exist.” They might not in architecture, but they do in the things that give rise to architecture: math, language, and human consciousness. Statements like “this sentence is a lie” and “I am nobody” are linguistic paradoxes. They’re like MC Escher’s Drawing Hands: destroying and recreating themselves over and over. Idioms like “pulling oneself up by one’s own bootstraps” are loopy. “This is not a pipe” is loopy. Barbershop poles are loopy.

One of the eye-opening parts of this book is how you start noticing strange loops all around you. The website you’re reading is powered by PHP, which stands for “PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor”. This isn’t a mistake: the language’s name is an acronym containing its own acronym inside it! Like spiders, strange loops exist closer to your body than you think.

But there’s more to strange loops than weird art and logic puzzles. Hofstadter seems to be poking towards a theory of consciousness itself.

In 1996, David Chalmers explicated the two main problems of consciousness. 1) How does a collection of atoms develop a consciousness (meaning a subjective experience, an internal monologue, or whatever). 2) Why does this happen? Why don’t we experience the world the way a robot might?

Hofstadter’s sense (never forcefully argued) is that strange loops are responsible for the consciousness we experience. Just as the three letters “PHP” contains an infinite number of “PHPs” inside them, our three-pound brains are able to “unfold” into something more than the sum of its parts, via iterations of very complicated loops. This doesn’t address the second of Chalmers’ questions, although in a later book Hofstadter compares the soul to a “swarm of colored butterflies fluttering in an orchard” – something attracted by the fruit, but not a part of the fruit. The loops don’t require conscious experience, the conscious experience emerges as a kind of froth when all of these loops combine.

This implies that an algorithm would be capable of introspecting about its own existence. A string of math on a very large blackboard would perceive the color red, and feel pain. It’s a provocative idea, but don’t expect to find this formulated with a QED at the end. As the constant artistic motifs suggest, GEB isn’t a hard science book. This is probably why people actually read it.

GEB is filled with illustrations, games, puzzles, and – most notoriously – dialogues inspired by Lewis Carroll. Some of these are astonishingly creative. The passage about the crab canon made me stop reading for a moment, because it was incredible, and I wanted to be able to remember it instead of immediately forgetting. It was mind expanding. Nearly mind-exploding.

Although GEB contains a primer on the basics of computer language, intellectual rigor isn’t the book’s goal. One of Hofstadter’s many interests is Zen Buddhism, which is our culture’s most potent form of anti-logic and as such is of interest to the student of the strange loop.

When the nun Chiyono studied Zen under Bukko of Engaku she was unable to attain the fruits of meditation for a long time. At last one moonlit night she was carrying water in an old pail bound with bamboo. The bamboo broke and the bottom fell out of the pail, and at that moment Chiyono was set free! In commemoration, she wrote a poem:

In this way and that I tried to save the old pail / Since the bamboo strip was weakening and about to break / Until at last the bottom fell out. / No more water in the pail! / No more moon in the water!

Zen never makes lessons easy for the student: you’re the one who has to do the work and become cosmic. But GEB makes the road far more fun than it has to be. What stands out about Hofstadter’s prose is how readable it is. Hofstadter isn’t a wordsmith, he’s a word alchemist, making dull things sparkle. The prelude to my edition contains a digression in the difficulties he had typesetting the book, which sounds as gripping as Hannibal crossing the Alps. (There’s also a somewhat cringeworthy part self-flagellating about the how the original printing of the book uses the default male voice.)

So is “loopiness” the way a collection of atoms can collectively seem to think, reason, and experience? The book leaves me unsure, as I think it was meant to. It’s the world’s longest Zen koan, fragments of information that never coalesce into a hard idea, but seem to get me closer to enlightenment than I was before.

Interesting aside: Godel, Escher, and Bach are three wise men (initials GEB), also the three wise men of the Nativity tale are Gaspar, Melchior, and Balthazar (initials GMB), also M is E rotated 90 degrees, also they brought gift of gold, frankencense, and myrrh (initials GFM), also F is the letter after E in the Roman alphabet, also “Godel” is nearly an anagram of “gold”, also I lied when I said this part was interesting.

No Comments »

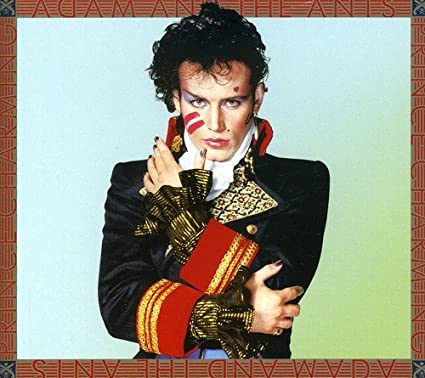

Bowie had a stock response to chameleon comparisons: “a chameleon’s trying to make you ignore him…that’s not my ambition!” Nor was it Adam Ant’s, who came from a similar art school background and cycled through an even more outlandish cast of characters: Indian brave, highwayman, cossack: visuals that sold (and were sold by in turn) some of the most exciting songs of the early 80s.

The first Adam and the Ants record is jittery, cold, and fraught, like ice cubes rattling in a glass. The second is a much easier listen, featuring powerful African-influenced drumming and really catchy songs. This is the third, which, as the title would suggest, is extremely charming and easy to like. It thus overcomes big problems, such as nearly every song on side B sucking.

It’s made of similar stuff to Dog Eat Dog, meaning sharp layers of vocals and guitars interspersed with empty space that crackles with energy. There isn’t the omnipresent Burundi drumming of Dog, but the busy tom fills achieve much the same effect. “Scorpios” is a nice, sprawling song with horns and many-tracked vocals that seems to stretch itself out on the airwaves. “Picasso Visita El Planeta De Los Simios” is even better, featuring lacerating funk-inspired guitar. “Stand and Deliver” is an amazing classic that summarises Adam Ant’s career, like a leaf that looks exactly like the tree it came from. Energetic danceable post-punk decked in brilliant visuals that saturate the music beneath it.

Quality control issues become evident as Prince Charming progresses. “Mile High Club”: dogshit. “Mowhok”: dogshit. “Ant Rap”: dogshit inexplicably released as a single. This is another trend of Ant: about half the songs absolutely do not work, despite containing similar ingredients as the ones that do. At least the bad songs mostly run together this time, so skip button jockeying isn’t necessary.

Ant broke through in the gulf between two eras, like a surfer trading one wave for another. The Ants were originally signed (according to Adam) because Decca Records wanted “in” on the then-waning punk rock trend, and grabbed the nearest band to hand. Then they blew up in the MTV music video era, when listeners started using their eyes as well as their ears and it began to pay to not be an absolutely hideous fucking goblin.

You know what they say about Elvis: 90% of what he did was worthless, and the last 10% made him king. Adam Ant was inconsistent, but when he was good, he was very good. You might say he burglarized the king.

No Comments »