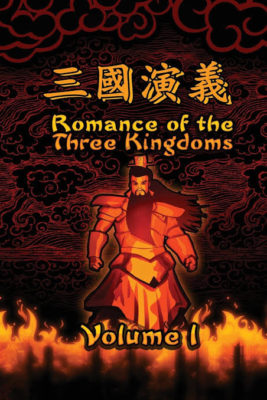

A doorstop-sized work of historical fiction from 14th century China. At eight hundred pages, nearly a million words, and a thousand named characters, it has broken hardier men than you. Romance of the Three Kingdoms is one of those Mount Everest type books – can you possibly finish it?

It’s also the world’s first videogame. Explanation incoming.

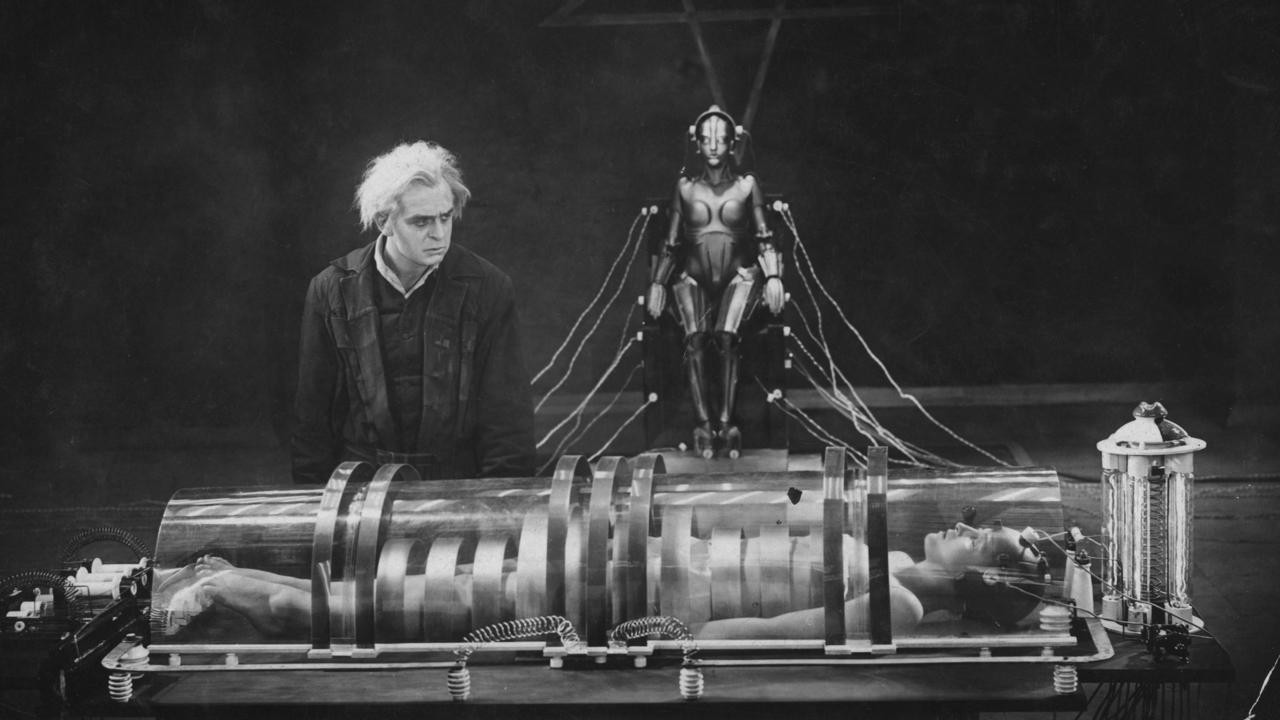

Sometimes art has content that suggests it belongs to a different medium. For example, the first film directors had a background in theater, and the movies they produced are often stunningly derivative of stage plays.

Watch a film from the 1920s and you’ll see lengthy static shots, minimalist editing, flat and declamatory acting, etc. Only in the middle period of Hollywood’s golden age did the techniques and approaches of film qua film emerge. Early films didn’t leave the vaudeville behind: they’re well made, but…they’re not exactly movies.

Romance of the Three Kingdoms is like that, but instead of being a play disguised as a movie, it’s a videogame disguised as a book.

More specifically, a strategy game. It reminds me of a six hour Age of Empires II game fought between skilled and stubborn adversaries amidst a mounting pile of energy drink cans. Battles without end. Thousands of men thrown into a woodchipper, often gaining nothing, or winning a victory that gets reversed minutes later. Numberless acts of heroism, which you see from God’s perspective and soon don’t even notice.

It’s about the fall of the Han dynasty and the three kingdoms (Wu, Wei and Shu) that ascended in the aftermath, trying to fill the power vacuum. They do this through a complex and Machiavellian mix of marriage, wizardry, and battles so bloody that it seems the population of medieval China gets slaughtered three times over.

The famous opening line “The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been” was not written by Luo Guanzhong, but was added centuries later. Nonetheless, it sums up his text: cyclical periods of destruction and renewal. Events are either meaningless or all-meaningful, depending on your perspective. There’s nods to “empty boat” style Taoist philosophy at times. The soil drinks blood. The soil then produces trees. The trees are used to make axes. The axes…

It’s hard to describe Romance without making it sound like the dullest book ever. It’s not. Nor is it the second dullest book. It’s actually interesting, once you crack the “code”.

The worst way to read it is like a traditional novel. Forget rising and falling action, dramatic climaxes, etc. Romance of the Three Kingdom’s intense moments come out of nowhere like monsoons, blow the lives of characters to pieces, and then end. Also, large parts are based on history, which is under no obligation to be satisfying to anyone. A better way is to view it like a growing plant: continually evolving in a way that’s no more and no less sensible than real history or the life of the reader.

And it’s thrilling. Despite the nihilism of the whole, you’ll still feel tense when Cao Cao fails in his plot to assassinate Dong Zhuo, and cheer at cunning method Zhou Yu uses to overcome an enemy fleet. Certain moments (such as the Battle at the Red Cliff) are as cinematic as Game of Thrones. And there are passages that would fascinate anyone with an interest in cultural anthropology and medical history. For example, the great hero Liu Bei’s reaction when he sees weapons inside his bridal apartment.

The bridegroom turned pale. Bridal apartments lined with weapons of war and waiting maids armed! But the housekeeper of the lady said, “Do not be frightened, O Honorable One! My lady has always had a taste for warlike things, and her maids have all been taught fencing as a pastime. That is all it is.”

“Not the sort of thing a wife should ever look at,” said Liu Bei. “It makes me feel cold, and you may have them removed for a time.”

[…]

Lady Sun laughed, saying, “Afraid of a few weapons after half a life time spent in slaughter!”

One wonders at what Luo Guanzhong is trying to depict here. Is Liu Bei suffering from what we today call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder?

The biggest challenging to climbing Mt Romance is the colossal cast of characters. To reach the end, you need to develop a sixth sense as to which characters are important to the plot and which ones will never be seen again. A lot of the characters have similar names. It can be hard to separate Zhang Fei from Zhang He. Maybe I’m a racist colonial paleface who thinks all Chinese names sound the same. But maybe not – Luo Guanzhong seems to be winking to the reader at times, such as in this (humorous?) scene where a woman vows to only marry a man with the same name as hers:

“Why did you trouble your sister-in-law to present wine to me, brother?” asked Zhao Yun.

“There is a reason,” said the host smiling. “I pray you let me tell you. My brother died three years ago and left her a widow. But this cannot be regarded as the end of the story. I have often advised her to marry again, but she said she would only do so if three conditions were satisfied in one man’s person. The suitor must be famous for literary grace and warlike exploits, secondly, handsome and highly esteemed and, thirdly, of the same name as our own. Now where in all the world was such a combination likely to be found? Yet here are you, brother, dignified, handsome, and prepossessing, a man whose name is known all over the wide world and of the desired name. You exactly fulfill my sister’s ambitions. If you do not find her too plain, I should like her to marry you and I will provide a dowry. What think you of such an alliance, such a bond of relationship?”

Romance of the Three Kingdoms might also be an early example of the Draco in Leather Pants phenomenon. The antagonist of the tale is clearly meant to be Cao Cao of the Wei kingdom, but he’s probably the strongest and most interesting character in the story, and a lot of people seem to view him in a positive light. Tumblr, of course, has an active community of Cao Cao stans.

But Romance isn’t a character study, it’s a videogame. The market seems to back this idea up. Usually classic works of literature attract a slew of movie adaptations, and maybe a single throwaway text adventure game made in 1984 by Infocom. But according to Wikipedia, Romance of the Three Kingdoms has been adapted to film eight times, to television twenty-four times, and as a game fifty seven (!) times. The book keeps rejecting its paper and clothing itself in binary. There might be three kingdoms, but ROTTK truly belongs in the realm of ones and zeros.

No Comments »

“I don’t like sand. It’s coarse, and rough, and irritating, and it gets everywhere,” – Albert Camus

Western horror relies on convention – Bram Stoker’s vampires, Shirley Jackson’s haunted houses, and Romero’s zombies. By contrast, Japanese horror more often relies on free-standing symbols and images – Kôji Suzuki’s rings of light, Junji Ito’s spirals, and Shinya Tsukamoto’s metal sculptures.

Both approaches have strengths and weaknesses. Art rooted in convention is easier to understand: the audience automatically comprehends Slasher Movie #23532 in light of Slasher Movie #23531 (or the last one they remember). But it’s boring, and makes you a slave to the past: modern horror film is consequently a cesspool of spooky dolls and cars that won’t start and ghosts in mirrors and clanging ADR. By contrast, Japanese horror (at its best) achieves a monolithic starkness: I gave up looking for things like Suehiro Maruo’s Paranoia Star because I couldn’t find any.

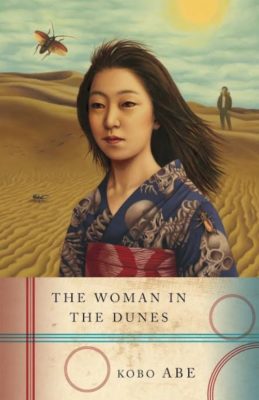

The Woman in the Dunes is an eerie psychological novel about…sand.

An amateur entomologist is seeking a new kind of insect in rural Japan. He ends up trapped in a deep pit of sand. He has food and water and even female companionship (although she seems odd), but no way of escaping. This is not an accident. Someone just out of sight has planned this fate for him. He has a little shack that he spends hours each day sweeping clear of sand (uselessly; the wind blows it straight back in). He can’t contact anyone from the outside world. They’ll declare him dead and maybe they’ll be right to. His horizons are made of sand.

The Woman in the Dunes might not be a horror novel, as I don’t think Kobo Abe was trying to frighten. Kafka’s a better comparison. Nonetheless, I’m now aware of “ammophobia” – fear of sand. More specifically: fear of sinking into sand, swallowing sand, having sand grains between your toes, and so on. Just as Uzumaki left me uncomfortably aware of spiral shapes, I put this book down and was plagued by thoughts of sand.

It’s creepy stuff. Silken, fluid, deadly. Viewed under a microscope, sand is beautiful, but it’s inhospitable to human life, and defiant of mankind’s attempts to control it. You can sculpt a castle of sand on the beach, but the next day, it will be gone. But won’t the house you live in be gone someday, too? All of mankind’s buildings, on a long enough timescale, will become sand.

This is sort of how Kobo Abe’s protagonist rationalises his fate. The outside world is just temporarily rearranged sand and dust, so there’s no reason to want to go back. Being trapped in a hole is probably a privilege; he gets to see the truth. Ozymandias’s kingdom wasn’t overtaken by sand, it was sand.

There’s a livestreamer called Dellor who plays Fortnite and other videogames. He has a PO box, and if you mail him a package he’ll open it on stream. Occasionally, he receives sand. I’m not sure if a single person is behind this, or if it’s a shared joke among his fans. He’ll rip open an envelope, and sand will spray across his apartment. He gets keyboards with sand packed in between the letters. Once someone sent him an airsoft pistol with sand stuffed into the barrel. This annoys him, because (as the narrator of The Woman in the Dunes could confirm) sand is extremely hard to remove. No matter how much you vaccuum a carpet, in six months you’ll walk over it barefoot and feel the bite of a silica tooth: a reminder of our fundamental lack of control.

Western horror can be likened to a vine, which can be followed back to its root no matter where it goes, and J-horror to a series of mushrooms, which sprout out of the ground with no visible connection to each other. Or perhaps particles of sand. The Woman in the Dunes exemplifies the J-horror approach, even if it might not be J-horror. It has one idea. One single idea. It could have been written even if no other book had ever been published. It does not want to be the first book in the series, or to answer questions raised by another book, or to get adapted into a movie.

The Woman in the Dunes doesn’t even want to be entertaining (and frequently, it isn’t). It exists to exist. No matter what momentary order we impose on sand, in the end, it has no purpose other than to be sand.

No Comments »

This isn’t good at all.

It’s barely even a movie: it’s like a long episode of Batman: The Animated Series featuring an occasional boob and a soundtrack of angsty, edgy mallcore. Music was shit-awful in the year 2000, and if you need a reminder, the first Slipknot album is shorter by thirty minutes, so listen to that instead.

What connection does it share to the original Heavy Metal? The title.

Instead of being an anthology, it contains a single bad story based on a graphic novel by Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles co-creator Kevin Eastman. The plot (narrated by someone who was probably making dramatic hand gestures in the vocal booth), involves the Arakacians producing an elixir of immortality and a secret key lost in space and a villainous asteroid miner and a tertiary villain who’s a dinosaur and an xtreme grrl heroine and a second xtreme grrl heroine and a plucky comic relief character who later becomes a sidekick and is replaced by a different plucky comic relief and a plot MacGuffin and Guy DeBord and Roland Barthes and asdf

The film is overloaded with detail and characters, because it’s basically a 170 page graphic novel jammed into a VHS player with a shoehorn. The screenplay couldn’t have more holes if it was made of swiss cheese. Where does the villainous Tyler get the weapons he uses for the raid on Eden? Why do none of those futuristic space-guns appear in the final showdown, which is fought with spears and swords? Why does becoming evil cause your hair to grow twenty inches?

Action girl #1 is played by Julia Strain. She has boobs. She beats the shit out of people who look at her boobs. What more character development do you need? Tyler himself looks like Ruber from 1998’s dose of box office strychnine Quest for Camelot, and exemplifies the problem I have with almost all “crazy” cartoon villains (such as Batman’s Joker): he turns sane and calculating whenever the plot requires it. The result is a mechanical artifice of a film where you can feel the interference of the writer on every frame. Why do characters do anything in Heavy Metal 2000? Kevin Eastman wanted them to do it.

“Calculating” applies to the film in general. There’s none of the sense of liberty and freedom of the original – instead it’s like a cold-eyed gambler, hedging every bet.

A great example is the SHOCKING ADULT CONTENT…which isn’t integrated in any way to the story! 95% of the film is a bland Saturday morning cartoon, then we get a pointless splash of violence and nudity, then the movie becomes a Saturday morning cartoon again. This is obviously intentional: they set up the movie so they could quickly chop all objectionable content and get a PG-13 rating. The quislings.

The animation is TV quality. Suffice to say that 90s cartoons looked as shitty as 90s music sounded: Heavy Metal 2000 is dark, lacks contrast, and has the palette of an Excedrin headache. Enjoy your browns, grays, and khaki greens. This is like playing Quake, right down to the underwhelming final boss.

This underscores the biggest offense Heavy Metal 2000 commits: it isn’t fun. Ren & Stimpy creator John Kricfalusi once said something (aside from “I thought she was 18, your honor”) that I find profound: animation’s strength is that it creates visuals that would be impossible with live action. If you animate visuals that are even more drab and bland than real life, you’re ignoring the possibilities of the medium. Heavy Metal 2000 doesn’t just ignore the possibilities, it hoists the black flag and directly repudiate them. What an ugly fucking film.

Heavy Metal was only barely successful. Heavy Metal 2000 went direct-to-video, and should have gone direct-to-landfill. It killed off attempts to bring Metal Hurlant to life for nearly another 20 years, before an anthology called Love, Death & Robots appeared on Netflix. I haven’t seen it and probably won’t: it’ll likely be a pandering joke full of references to Twitter and trans issues, with a villain called “Tonaald D’rump” or some shit. Heavy Metal is a nostalgic look at the past. As such, it’s best left in the past. The world did not and still does not need another Heavy Metal.

No Comments »