Halley’s Comet is a pale splash of starmilk that runs across the sky every 75 years. As it approaches the sun its frozen nucleus boils, becoming a gaseous tail a hundred million kilometers long.

Some people will see it twice. I expect to only see it once. All celestial phenomena are interesting, but Halley’s Comet is doubly so because it keeps coming back: a friend from space who can’t wait to see us again.

“Is there a point to this?” you ask, perceptive as always. Yes, by reading those words you are a few seconds closer to the Comet’s next appearance (28 July 2061). Here are some more. And some more. You’re welcome. It’s no trouble.

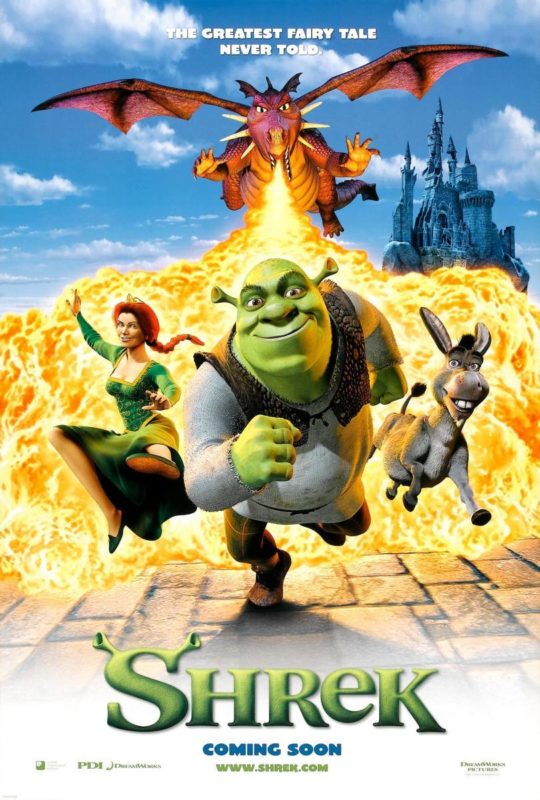

For a month at age 6, my favorite thing was Shrek. For a month at age 11 my favorite thing was again Shrek. Like the comet, Shrek exited and then re-entered my psychic horizon. And just as Halley’s Comet never comes back twice in the same form (it changes shape and albedo as it sublimates mass), Shrek didn’t come back in the same form. The first Shrek! (it had an exclamation point) was a children’s picture book by William Steig. The second Shrek was an animated movie by Dreamworks.

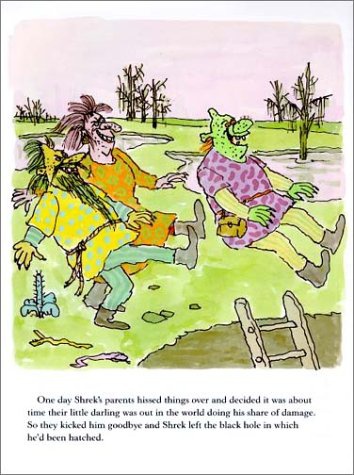

Let’s talk about the book first.

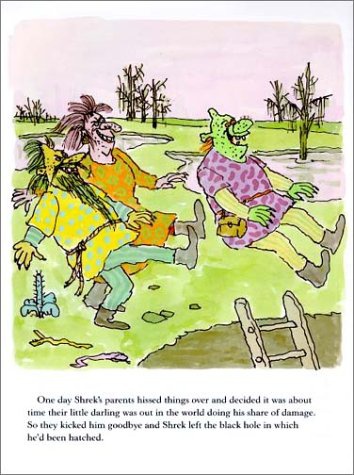

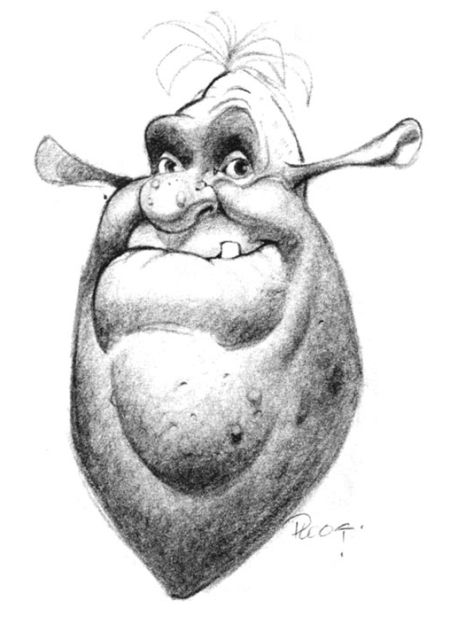

It’s 26 pages of brutal, scabrous art, with thick lines that often don’t join and colors eyedroppered from plates of slime infections. It’s the first time I can recall reading a book and thinking “I could have done a better job on the pictures”. Only later did I realize that “ugly” art can be intentionally so, and that this is some of the most challenging art to produce. There’s a world of difference between shitty drawings and drawings that use shittiness.

The story: Shrek is an revolting creature who roams around scaring people, animals, plants, monsters, and himself (after seeing his own face in a mirror). After being kicked out of home by his parents, Shrek wanders the land, seeking his destiny.

This isn’t a “Shrek’s not ugly, SOCIETY’S ugly for not accepting him! #LoveYourBody” kind of book. No, Shrek’s definitely ugly. Consummately repulsive. Pluperfecty loathsome. Also, he smells so bad that plants and flowers literally bend out of his way.

One of Thomas Aquinas’s arguments for God’s existence (Summa Theologiae 1:2:3) is that the “goodness” concept entails the existence of a maximally good being, ie God. Richard Dawkins has questioned this logic: does the concept of “smelly” require that a maximally smelly being exist somewhere? But after reading Shrek!, I think Aquinas had a point. Shrek is that smelly being.

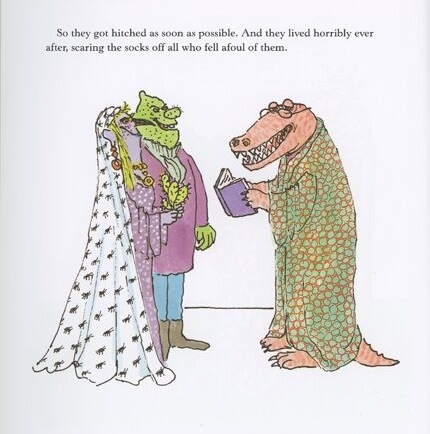

But is Shrek evil? It’s hard to say. Aside from one clearly bad deed (stealing a peasant’s lunch), most of his actions are morally neutral at worst. He gets in lots of fights, but only because the other person starts them, and he generally incapacitates enemies instead of killing them. He gains the princess’s consent before kissing her, which is something multiple Disney princes don’t do. He has a nightmare about being hugged and cuddled by children, but haven’t we all?

(Update: Halley’s Comet is coming closer. Or further away, rather. It’s complicated, see – it has to reach the far point of its orbit before it starts swinging back. A shortening of temporal distance requires an increase of astronomic distance. The universe is full of such paradoxes.)

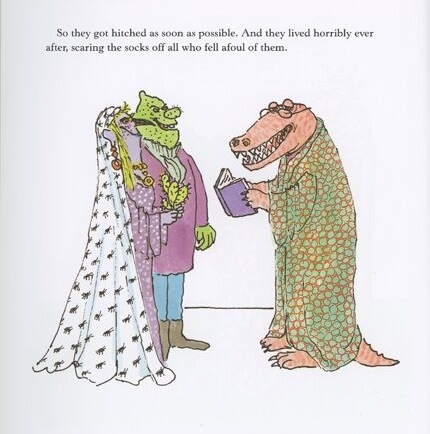

Stieg never “redeems” Shrek, or gives him a makeover, or transforms him into a handsome prince. Shrek is allowed to be what he is and look the way he does, and find happiness in his own way. Many beloved fairytales (the Ugly Duckling in particular) exhibit what Nietzche called slave morality. “You have flaws, but don’t give up! Maybe they’ll magically disappear!”

Well, sometimes they don’t. Shrek! gives it to you straight: you might have to sail the seas of life in adverse conditions. Many adult books don’t confront reality this well.

The book has zero passages describing Shrek as an ogre, by the way. He might be an extremely ugly man. Is there a “Humpty Dumpty is an egg” psyop going on where we collectively agree that he’s an ogre even though it’s not in the book? (Well, the back cover says he’s an ogre. But that’s hardly canon – authors usually don’t write their back blurbs.)

Published in 1990, Shrek! was aimed at preschoolers – although words like “blithe” and “varlet” and “churlish” and “carmine” probably caused some parents to reach for the dictionary. I like the author’s name. Stieg. All of the authors I grew up with had these ominous, evocative sounding names, usually beginning with S. Sendak. Stieg. Seuss. Shel. Stine. Names that made them sound like wizards in high towers, stirring bubbling cauldrons and summoning lightning. Surely no children’s fiction author would have a name like “Bob”.

All in all, a worthy book: Roald Dahl for kids who aren’t old enough for the real Roald Dahl. It’s well worth reading (or re-reading) while you wait for Halley’s Comet. 28 July 2061. Are you excited? I know I am. Soon.

But we still have the movie to discuss.

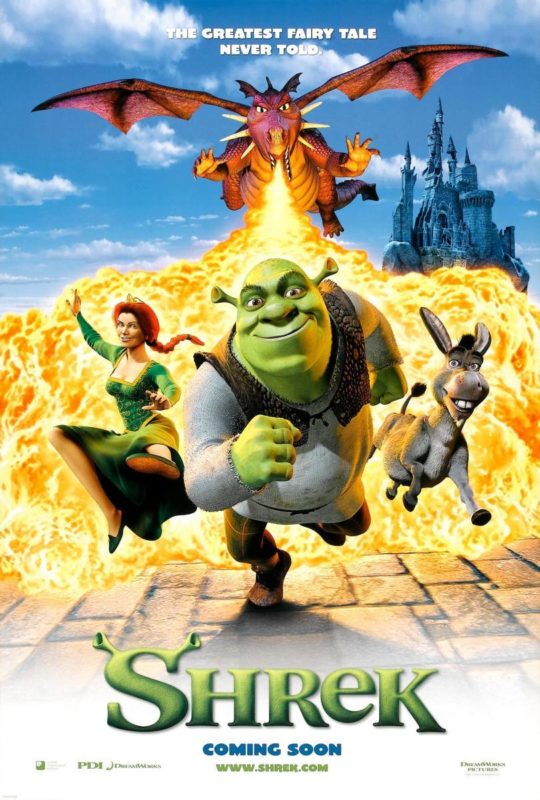

In 2001, commercials for a film called Shrek began rolling out. Stieg’s book? A distant memory. None of my friends had heard of it.

I saw the movie and it blew me away. I’d never imagined anything so funny, so clever, so sophisticated. This was clearly and inarguably the greatest film ever made.

I talked about it to everyone I could. I had the DVD, and spent hours playing with the special features (if you had a microphone, you could dub your voice over Eddie Murphy’s). If you were my friend and hadn’t watched Shrek, I genuinely thought there was something wrong with you.

I rewatched it in 2021, and it was unimaginably worse than I’d thought.

I hated almost every part of it: the plastic doll character design, the bad songs, the cheap pop references substituted for jokes, the “don’t judge people based on appearances!” message interspersed with cruel jibes about how short the villain is. Some computer animated films (Toy Story) have become timeless. Shrek has become ocular pollution: ugly and unfunny.

The movie seems generally well-remembered by others. I wonder how many of those “memories” occurred when the writer was 10, and if they’d survive a rewatch. I made it to the Matrix ripoff scene before mumbling to an empty room “You’re just…commenting on the fact that another movie exists! How is that funny?“

Some parts held up. The opening scene is fun and sells the movie well. There’s sharp writing at certain places (such as the Gingerbread Man sequence). The barely-disguised adult humor (“Lord Farquaad”) isn’t exactly funny but at least shows a creative team with nerve.

But nothing could save the movie from the cancerous pus-filled oozing blastoma sac of Eddie Murphy.

I laughed at the donkey as a kid. Why? He wasn’t saying anything funny. In fact, I barely understood him at all.

Well, because he masterfully created the appearance of being funny. Eddie Murphy is a reminder that much (or most) of humor is in the delivery. His cadence, vocal rhythms, and confidence are flawless, and make him seem like a comedian doing a tight five on national TV and nailing it.

But he’s saying nothing. He was like an air-guitarist performing awesome rock moves with empty hands.

Donkey: [Chuckles] Can I say somethin’ to you? Listen, you was really, really somethin’ back there. Incredible! Yes, I was talkin’ to you. Can I tell you that you was great back there? Those guards! They thought they was all of that. Then you showed up, then bam! They was trippin’ over themselves like babies in the woods. That really made me feel good to see that. Man, it’s good to be free. But, uh, I don’t have any friends. And I’m not goin’ out there by myself. Hey, wait a minute! I got a great idea! I’ll stick with you. You’re a mean, green, fightin’ machine. Together we’ll scare the spit out of anybody that crosses us.

[Roaring]

Donkey: Oh, wow! That was really scary. If you don’t mind me sayin’, if that don’t work, your breath certainly will get the job done, ’cause you definitely need some Tic Tacs or something, ’cause your breath stinks! Man, you almost burned the hair outta my nose, just like the time– [Mumbling] Then I ate some rotten berries. I had strong gases eking out of my butt that day.

Yep, that’s Eddie Murphy in Shrek. Don’t worry, they only let him blather like that for fifty minutes.

It’s clearly improv – a director sat Murphy in front of a mic and told him to go nuts, hoping for another Robin Williams’ Genie. But when the entire movie is littered with this sort of babble, it becomes grating, and then enraging.

The danger of writing a character who annoys other characters is that they will also likely annoy the audience. The 2000s were boom years for black actors with nails-on-chalkboard patter. Will Smith. Chrises Tucker and Rock. Tyler Perry alone is persuasive evidence that we need to means-test microphones before giving them to the black community.

In all, not a good movie.

But there’s a deeper level to all of this. A conspiracy, if you will. As soon as I read item 3 on this list, I heard the X Files theme playing in my head. Mostly because I was playing xfilestheme.mp3 on my computer while reading it.

Douglas Rogers (the art director) found a place there that was a magnolia plantation where he did research to get the look of Shrek’s swamp just right. It was perfect and exactly what he had been looking for, for the film.

While there, though, he was in for quite the big surprise. And that surprise was an alligator, that unfortunately, ended up chasing him.

Once again, this crew’s dedication is something else. Though, I’m sure he wasn’t expecting the alligator to run at him.

All I can say is I hope he felt it was worth every bit of running from the alligator because that is a seriously scary situation to be in all for research for work.

An alligator. In a swamp. One that’s very defensive of Shrek’s legacy. Where have I seen this before?

Damn.

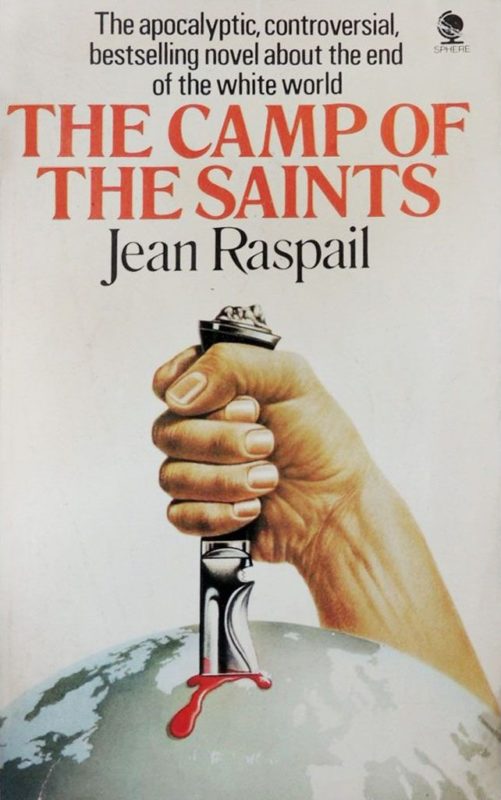

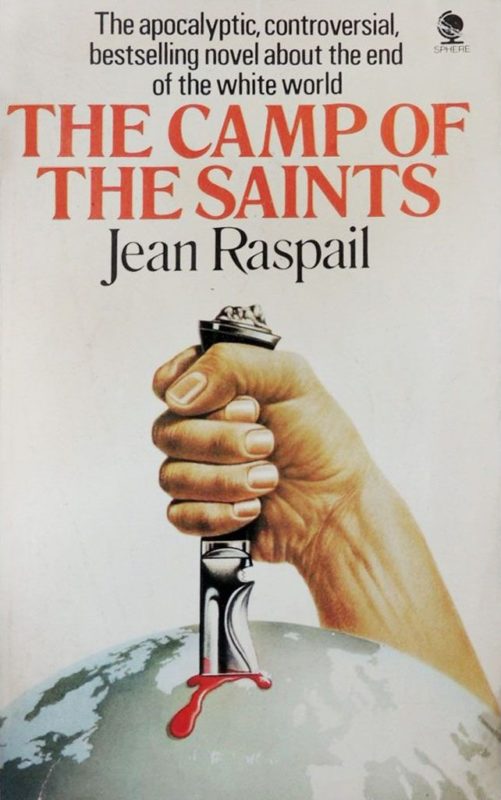

Le Camp des Saints is a 1970s anti-immigration novel that remains eternally relevant due to the efforts of pro–immigration activists. Every few months a new op-ed appears somewhere informing the reader that this book exists and is evil and racist. Like Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto, it’s hard to defend, easy to mock, and a useful albatross to hang around your opposition’s neck. Voltaire said “oh Lord, make my enemies ridiculous.” Saints is such an effective clown nose that it will remain in print for the next hundred years, or forever.

The setting is a dystopia. Overpopulation has turned the Third World into a simmering Malebolge of starvation and poverty, and a sea of refugees threaten to overwhelm the West (while deluded liberal politicians tunnel holes in the walls). The crisis reaches a head when an army of Indians (enabled by a weak, dissimulating “atheist philosopher” called Ballan) hijack a fleet and sail for France. As the armada approaches, the government faces a choice: should the refugees be allowed in? They deliberately only packed enough supplies for a one-way trip, and they’ll die if turned away.

To state the obvious, the book is indeed bigoted. Raspail does not like foreigners. They’re described as “a mass of human flesh”, “a million flailing savages”, “a river of sperm”, “unbridled, menacing hordes”, “cholera-ridden and leprous wretches”, “columns of ants on the march”, a “numberless, miserable mass”, “a welter of dung and debauch”, and more. Tolkien didn’t write about orcs with such vituperation.

Saints might be the most splenetic book to achieve mainstream success in a century. It’s written in squalling, thundering prose that seems shouted at the reader through a bullhorn. Characters are illustrated in one broad stroke, and usually never a second one. In the first pages we meet the first of many strawmen of the pro-immigration left – a white college kid who has embraced Islam and atheism simultaneously (?), is helping the refugees make landfall so they can destroy French culture (?!) and who wants to rape his sister (?!?!). But first he’s going to smoke pot and shoot dope on the beach. This character amazed me: caricatures that broad normally only appear in Jack Chick tracts.

Saints is a queasy and miserable nightmare. I doubt many finished it, and the ones who did probably didn’t immediately plan a re-read. But it has an intensity to it, and once you adjust to the content, it’s strangely readable. Raspail has a “Nouveau French” prose style that’s equal parts classicist and camp (“there was no lack of clever folk, willing, from the start, to spread endless layers of verbal cream, spurting thick and unctuous from the udders of their minds”). It’s a book written out of passion, not cynicism.

The moral issues Saints raises are interesting and important, however much you disagree with the book’s handling of them.

Race is a stalking horse for Raspail’s true issue: overpopulation. The Indians aren’t bad because they’re Indians, they’re bad because there are too many of them. They reproduced to excess, used up all their country’s resources, and now want to take other countries down with them. This might seem a distinction without a difference, but it creates a covalence with many thinkers and intellectuals from the period, not all of whom were on the far right.

Overpopulation was much on the public mind in the 70s (and 80s, and 90s). The ghost of Thomas Malthus) began stirring and rattling chains. “The population is doubling every forty years! How will we feed, clothe and house them all? What happens to the environment? We’re going to be back in the bad old days: wars, famines, plagues, deforestation. Wouldn’t it be kinder for everyone if we could…*cough*…control the population somehow?”

This is why your Infowars-obsessed dad keeps finding quotes by “elites” such as Ted Turner about reducing the population. It’s also the reason The Camp of the Saints was published by a mainstream press and read by academics, instead of “published” by a hand-cranked press at a neo-Nazi farmstead and “read” by the prosecution at the author’s own hate speech trial. “There’s too many people, and lots of them will have to die,” absolutely wasn’t a fringe viewpoint fifty years ago, and Raspail’s hymn had many voices in the choir, although most hid their views in liberal language.

In 1968, Paul Erlich wrote The Population Bomb, full of cheery asides like “the battle to feed all of humanity is over”, and “hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death.” The book sold hundreds of thousands of copies and got its author on NBC’s Tonight Show. In 1995 Lester R. Brown wrote a book called Who Will Feed China? (making China sound like the monster in Little Shop of Horrors, ravenously eating), complete with a photo of sad-looking Chinese kids on the cover. Radical leftist Pentti Linkola spent decades recommending drastic population reductions by coercive means, as seen in his famous “lifeboat ethics” metaphor.

“What to do, when a ship carrying a hundred passengers suddenly capsizes and there is only one lifeboat? When the lifeboat is full, those who hate life will try to load it with more people and sink the lot. Those who love and respect life will take the ship’s axe and sever the extra hands that cling to the sides.”

Note that these brutal “sever the extra hands” solutions were always directed at brown people. White people used far more than their share of the planet’s resources, but somehow it was always the mother in Senegal with seven children dooming the world. It’s an uncomfortable legacy that the left has spent a lot of time grappling with since (Google “eco-fascism” for more), and if you want to throw tomatoes at Raspail, save a few ripe ones for the 70s environmentalist movement, too.

But how the years condemn. Here’s Raspail’s introduction.

I HAD WANTED TO WRITE a lengthy preface to explain my position and show that this is no wild-eyed dream; that even if the specific action, symbolic as it is, may seem farfetched, the fact remains that we are inevitably heading for something of the sort. We need only glance at the awesome population figures predicted for the year 2000, i.e., twenty-eight years from now: seven billion people, only nine hundred million of whom will be white.

This year arrived twenty years ago, but Raspail’s world did not come with it. Something happened instead that he didn’t expect: the Third World began rising out of poverty. The choice between saving the poor and saving ourselves never occurred: we can do both. The game is survival is not always zero-sum.

But I’m interested in the moral quandary Raspail poses. First, let’s grant his scenario. A million Indians are waiting to enter France. If they, they’ll destroy Western civilization (in the same sense that Spanish invasion of the new world “destroyed” the Meso-American civilizations). Don’t ask questions. This is the choice. What’s the correct thing to do?

I think the refugees should still be allowed in. Killing a million people is bad. And although the death of Western civilization might be worse, you’re weighing a certain bad at probability 1 (a million people will definitely die if we sink the ships), vs a maybe-bad at probability <1. How sure are we that Western civilization will be destroyed? We might have misunderstood the situation. It might be that Western civilization passes without mass suffering. The two evils aren’t equivalent. Throwing a brick blindly into a crowded shopping mall isn’t the same as throwing it in a remote wilderness, even though you can conceivably injure people in both cases.

Comparisons between Third World immigrants and Spanish conquistadors can only take us so far. Spain didn’t wipe out the Meso-American empires by flooding them with sheer numbers of Spaniards. They wiped them out with a superior technology base (steel, firearms, horses), as well as novel diseases that the natives lacked immunity to. This isn’t the case with refugees. They’re limited in their ability to cause harm. This isn’t to say there aren’t issues associated with immigration, but it’s not the same set of issues raised by an invading army or a superplague.

Lastly, we have to be pragmatic. If Western civilization is so fragile that a million people on ramshackle boats can overwhelm it, it was weak and wouldn’t have lasted much longer anyway. It may as well help some people as it falls.

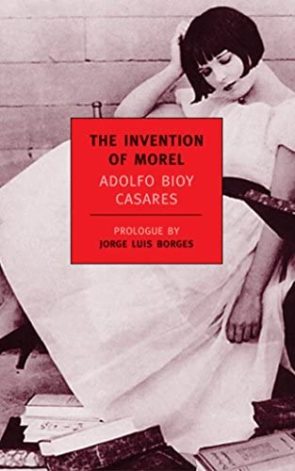

Adolfo Bioy Casares was an Argentinian author, and The Invention of Morel (1940) is his most famous work.

At 100 pages long, the book is sleek and deadly, like one of those rockets with every planar surface graded away to minimize wind drag. It evolves Siddhartha-like through several distinct forms: a Robinson Crusoe-like adventure tale of a man surviving on an island, then a “William Wilson”-like horror story about doubles and dopplegangers, then a disturbing science fiction tale from the speculative side. Prominence romance elements keep the story anchored throughout, although it’s not romance of the usual kind.

The island-stranded protagonist doesn’t warrant a backstory: he has done something bad and is a fugitive from justice; that’s all we know. He’s not alone on the island: there are some dwellings that are inhabited by strange tourists. He soon grows afraid of these people, and not because he thinks they might report him to the police. There’s something very peculiar about them. Their party never ends. They play two pop songs – over and over – until the sound seems hammered permanently into the air.

In time, he notices a beautiful young woman. He’s attracted to her – even though there’s something unusual about her too. She doesn’t react to him, and she behaves as if he’s not there. Confusion about the island and where exactly he’s ended up cause him to explore, find things he’s not supposed to find, and make some world-shattering (or mind-shattering) discoveries.

Adolfo Bioy Casares is often compared to Borges. They were friends, countrymen, colleagues. Bioy’s imaginative faculties are dimmer than Borges, but he’s more successful as a teller of tales. Borges work is a little like a puzzle box: there’s satisfaction in watching pieces slide together and a solution appear, but often there’s not really a story there. Bioy is a lot like Edgar Allen Poe (or, hell, Edogawa Rampo) – he takes dry ideas and wraps human flesh around them, making his scenarios seem real and scary. The story’s third act is as nailbitingly intense as anything I’ve read in recent memory.

Invention of Morel is a jostle of influences and sources, both fictional and nonfictional. HG Wells The Island of Dr Moreau is a pretty obvious inspiration (Mor-el/Mor-oh). The character of Faustine is based on silent film star Louise Brooks, who Bioy was reportedly obsessed with. But that’s the interesting thing – did he ever really know her?

Louise Brooks was famous for her pictures, maybe immortal because of them, but an actress’s fame is a kind of living death. Brooks is going to smile and giggle and tempt in Pandora’s Box for a thousand years, or however long people still watch it…but the smile will be cold, the laughter will be as robotic as that of a coin-operated machine, she’ll walk eternal steps dictated by a film director. The real Louise Brooks died long ago. The fake one lives on, the way an insect’s molted shell often outlasts the soft, pulpous creature that crawled out of it. But which of the two did Bioy fall in love with? Certain primitive humans think cameras steal souls, and maybe they’re right to.

Nonfiction influences include Malthus’s economic theories, which end up joined with the book’s primary concerns in an interesting way, and the de Broglie hypothesis of matter being made up of waves. More generally, it plays on terms set by George Berkeley’s subjective idealism – the idea that perception is king, and that physical objects only exist to the extent that our senses perceive them. The idea is that if you overlay a combinations of visual, audible, tactile (etc) data using a machine, you will have, in some sense, created the thing you’re depicting. Bioy’s version of this technology is vague and impossible, but it’s not altogether absurd as a concept. A lot of things in this universe seem to hinge upon observation. And a lot of technically nonexistent things (such as nations) exist because we will them out of the ether.

The Invention of Morel seems well ahead of the curve, which is generally where you want science fiction to be. It presages things like the parasocial relationships of the online era. I enjoy books that drag together unlike influences together like oxen and make them pull the ploughshare of a story, and few achieve this with Bioy’s skill.