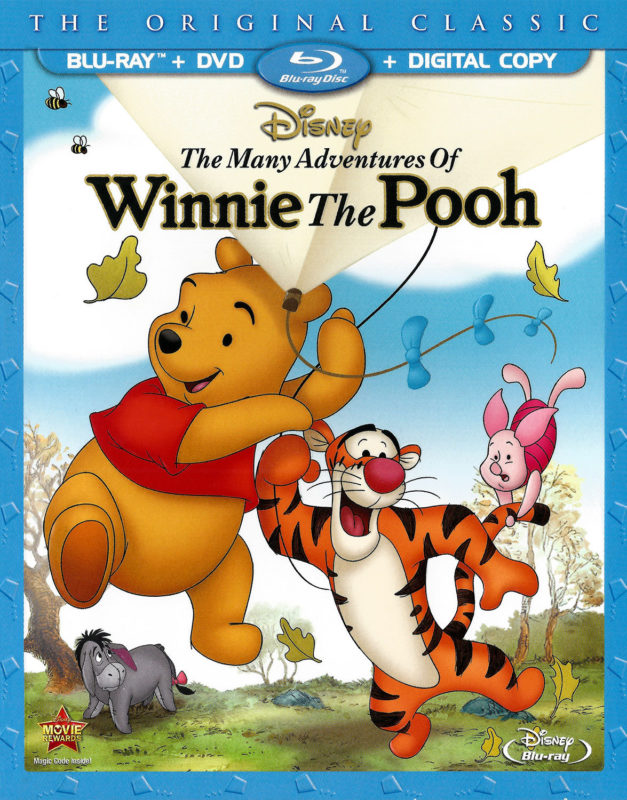

In this upsetting and unfair Xi Jinping biopic a cartoon bear wanders around the woods making bad decisions and singing songs. It’s one of the few classic Disney films I hadn’t seen. I thought that watching it would restore my sense of childhood wonder, then I remembered I never had a sense of childhood wonder.

If you’re wondering what constitutes “many”, it’s three. The film contains the featurettes “Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree” (1966), “Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day” (1968), and “Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too” (1974), which hail from the Wolfgang Reitherman era of the company and serve as reasonably accurate adaptations of select AA Milne stories.

The animation has that rough 60s Disney quality, where you can almost see flickers of pencil schmutz. Vocal talent includes Sterling Holloway as Pooh, John Fiegler as Piglet, and Stan Freberg as a “laughing honey pot” (he was not credited for this monumental role, in an injustice Tinseltown has yet to reckon with). The total running time is just 74 minutes. This didn’t seem particularly short in 1977 (Dumbo is exactly an hour and four minutes long), although it does now that multiplex theater timeslots are forged in titanium.

“Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree”: Winnie the Pooh is a revolting fatbody who eats everyone’s honey while remarking that he’s “grumbly in his tumbly (sic)”. He becomes so fat that he gets stuck in Rabbit’s tunnel, and the entire gang (including a gopher who isn’t in the original book) combine their talents to free him. Pooh looks disgusting in his red shirt – buttocks protruding. Very very disrespectful.

I wonder why certain creative decisions were made. Why does Pooh keep his HUNNY on the highest shelf (which he can only reach while standing on a chair?) Is he stupid? Or does it hint at hidden character depth – Pooh subconsciously trying to break his HUNNY addiction, the way a compulsive smoker might “hide” their cigarettes?

The most probable explanation is to fit the music to the action cues. The shot begins with sixteen bars of music remaining (“with a hefty, happy appetite, I’m a hefty, happy Pooh!” x2), and Pooh must waste a few seconds doing something (like fetching a chair) for the song to end at the triumphant moment he grabs the HUNNY.

Also, Pooh can rotate his head 360 degrees. This might have gotten laughs in 1977; now it looks like The Exorcist.

“Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day” sees Hundred Acre Wood being flooded by a fierce storm, with all the animals being washed away atop various bits of detritus while regretting their decision to vote for Bush. It contains an eerie dream sequence where Pooh floats out of his body and has a nightmare about heffalumps. Doug Walker used to call these “Big-Lipped Alligator Moments” – animated sequences that are completely pointless, nightmarishly over-the-top, and never referenced again. It’s also notable as the introduction of Tigger, whose name I don’t enjoy typing. My left index finger is millimeters away from an incident. A wiser man would play things safe and call him Tigga, but I persist.

As with Mickey Mouse and the Beanstalk, the film frequently breaks the fourth wall, or rather the fourth page. The narrator will hold conversations with characters in the book, and so forth. This gets tiresome, although it allows for some fun animation.

“Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too” is about a bouncing Tigger who bounces too much and gets stuck up a tree at the top of the page. He learns that he’s scared of heights. His friends tell him to stop being a pussy and come down, but he simply can’t, and eventually the narrator intervenes, rescuing poor Tigger by folding the page. There’s another Big-Lipped Alligator Moment. There’s a poignant animated scene that was possibly created for the film’s release (I’m not sure), detailing Christopher Robin’s plans to go to school and perhaps get on lithium to stop his hallucinations of talking animals.

Winnie the Pooh belongs to Disney and will continue to do so until at least 2026, when the character enters the public domain. Pooh’s ownership history is complicated – in 1930 AA Milne sold the character to someone called Stephen Slesinger, who died in 1953, at which point his widow licensed the rights to Disney in exchange for regular royalties. Lawsuits from Slesinger’s estate ensued, alleging that Disney was welshing on said royalties. This resulted in a decades-long legal slapfight that descended into low comedy – apparently Slesinger’s estate literally hired goons to rake through Disney’s trash for shredded documents. Pooh is big business, bringing in billions of dollars a year. It’s not impossible that Disney would have been bankrupted in the 1980s without the Pooh MUNNY jar.

What led Walt to acquire the rights to AA Milne’s Pooh stories, and thus (probably) save his own company? Apparently, his daughter liked them. That was all it took.

If Diane Disney had possessed different reading tastes, the Disney canon might look totally different. Lady Chatterley and the Tramp, or The Rescuers Down and Out in Paris and London, or Make Mein Kampf, or The Dalmatian With A Hundred and One Young. HP Lovecraft owned a cat. It wasn’t called Tigger.

Wow! What a show!

As a father of nine, I can testify (amen!) that it’s a challenge raising Christian children in today’s increasingly secular world. The younger generation is so obsessed with their “iPhones” that they forget the REAL unlimited data plan…prayer! They have Candy Crush on their tablets instead of the 10 commandments. They’re waiting on a “text from bae” when God’s waiting on them to “reflect and pray”. They’re “420 blazing it” when they should be “420 PRAISING it”!

It’s good to know there’s still wholesome Christ-centered animated TV shows out there. Yes, I’ll admit I was nervous when my kids starting watching this. Talking vegetables? And they don’t wear pants? There seemed no end to the perverted possibilities. I’m still trying to repair the damage done to my kids after the The Incredibles 2 exposed them to the words “h*ll” and “d*mn”, and I was eager to avoid another fiasco.

Thankfully, my fears were groundless. This is a marvelous show. Children of all ages will be glued to the screen, laughing at the adventures of Bob the Tomato, Larry the Cucumber, and all their friends. And don’t be surprised if YOU crack a smile – this one’s fun for the whole family!

Yes, sometimes Bob and Larry make mistakes, or act out of impulse. But they always learn a valuable, Christ-centered lesson that kids will take to heart and apply in their own lives. And they’ll never forget that no matter what we do wrong, God is greater than our sins. Amen!

I do question the decision in Where’s God When I’m Scared to write a song discussing the “boogeyman”. As I understand it, the boogeyman is based on a p*g*n diety, and while this might seem harmless it could easily lead to teenage experimentation with dangerous pro-occult media like Dwarf Fortress and Avengers: Endgame. Thankfully, the word is only used a few times and I’ve bleeped it out on my VHS tape.

Yes, it hurts that I have to leave my kids during my lengthy business trips evangelizing the gospel to teenage males inside a San Fran porta potty with a circle cut into the wall. But thanks to this show, I know my children are in good hands – or stems, as the case may be!

In closing: ten out of ten crosses. For once, your children will be wagging their “tales” for the chance to eat their “veggies”!!!

Halley’s Comet is a pale splash of starmilk that runs across the sky every 75 years. As it approaches the sun its frozen nucleus boils, becoming a gaseous tail a hundred million kilometers long.

Some people will see it twice. I expect to only see it once. All celestial phenomena are interesting, but Halley’s Comet is doubly so because it keeps coming back: a friend from space who can’t wait to see us again.

“Is there a point to this?” you ask, perceptive as always. Yes, by reading those words you are a few seconds closer to the Comet’s next appearance (28 July 2061). Here are some more. And some more. You’re welcome. It’s no trouble.

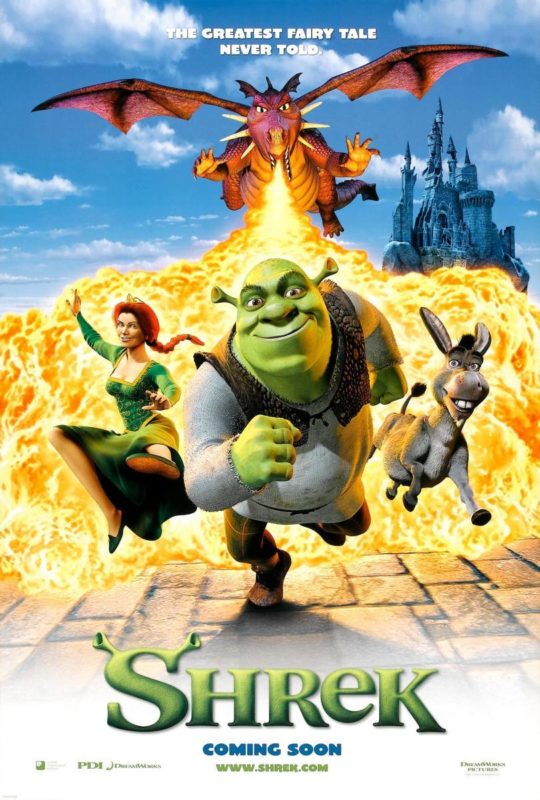

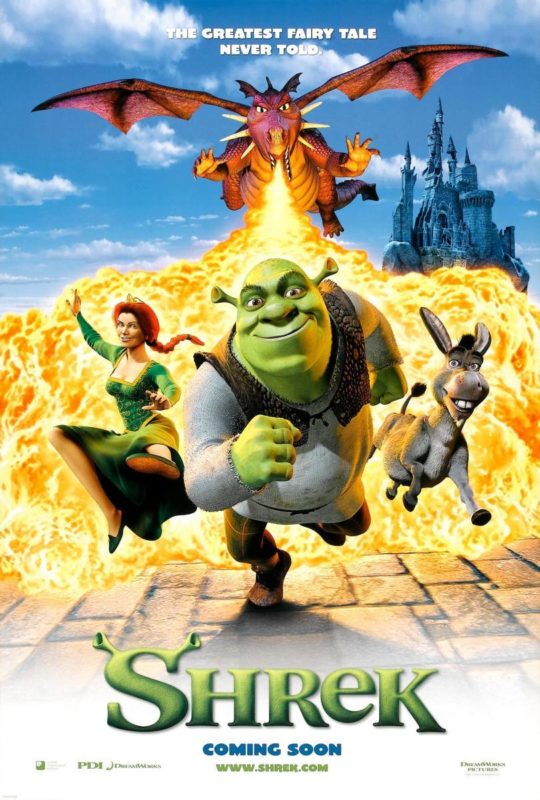

For a month at age 6, my favorite thing was Shrek. For a month at age 11 my favorite thing was again Shrek. Like the comet, Shrek exited and then re-entered my psychic horizon. And just as Halley’s Comet never comes back twice in the same form (it changes shape and albedo as it sublimates mass), Shrek didn’t come back in the same form. The first Shrek! (it had an exclamation point) was a children’s picture book by William Steig. The second Shrek was an animated movie by Dreamworks.

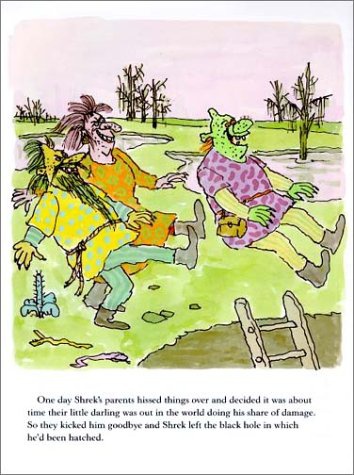

Let’s talk about the book first.

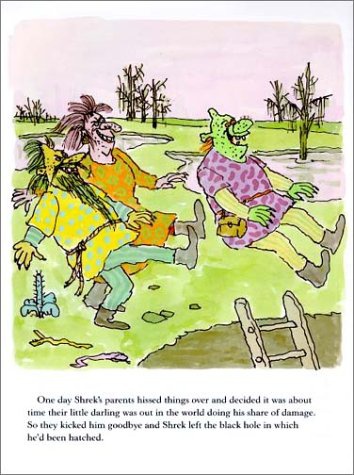

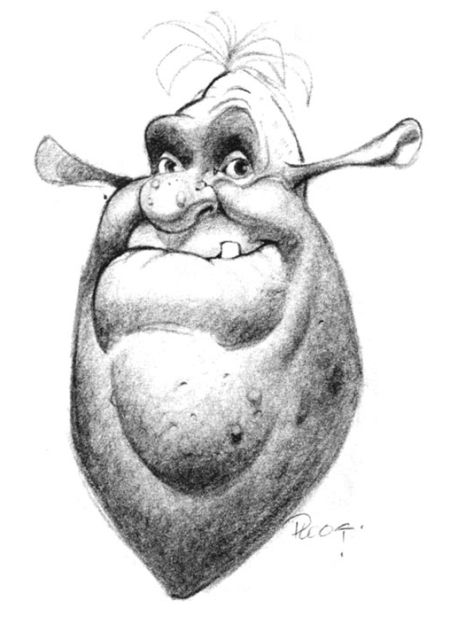

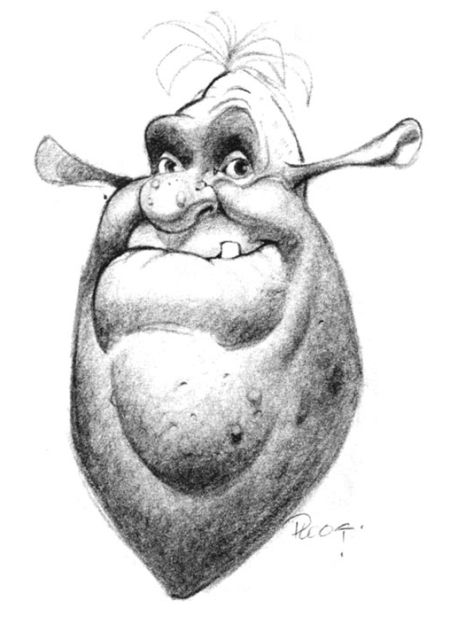

It’s 26 pages of brutal, scabrous art, with thick lines that often don’t join and colors eyedroppered from plates of slime infections. It’s the first time I can recall reading a book and thinking “I could have done a better job on the pictures”. Only later did I realize that “ugly” art can be intentionally so, and that this is some of the most challenging art to produce. There’s a world of difference between shitty drawings and drawings that use shittiness.

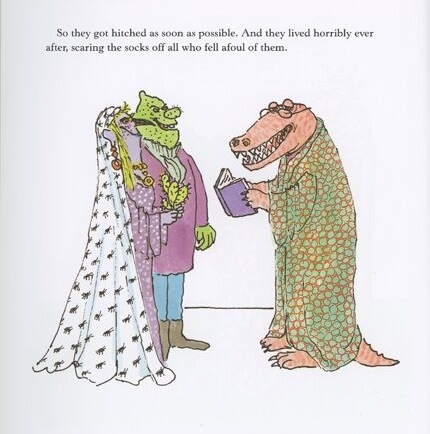

The story: Shrek is an revolting creature who roams around scaring people, animals, plants, monsters, and himself (after seeing his own face in a mirror). After being kicked out of home by his parents, Shrek wanders the land, seeking his destiny.

This isn’t a “Shrek’s not ugly, SOCIETY’S ugly for not accepting him! #LoveYourBody” kind of book. No, Shrek’s definitely ugly. Consummately repulsive. Pluperfecty loathsome. Also, he smells so bad that plants and flowers literally bend out of his way.

One of Thomas Aquinas’s arguments for God’s existence (Summa Theologiae 1:2:3) is that the “goodness” concept entails the existence of a maximally good being, ie God. Richard Dawkins has questioned this logic: does the concept of “smelly” require that a maximally smelly being exist somewhere? But after reading Shrek!, I think Aquinas had a point. Shrek is that smelly being.

But is Shrek evil? It’s hard to say. Aside from one clearly bad deed (stealing a peasant’s lunch), most of his actions are morally neutral at worst. He gets in lots of fights, but only because the other person starts them, and he generally incapacitates enemies instead of killing them. He gains the princess’s consent before kissing her, which is something multiple Disney princes don’t do. He has a nightmare about being hugged and cuddled by children, but haven’t we all?

(Update: Halley’s Comet is coming closer. Or further away, rather. It’s complicated, see – it has to reach the far point of its orbit before it starts swinging back. A shortening of temporal distance requires an increase of astronomic distance. The universe is full of such paradoxes.)

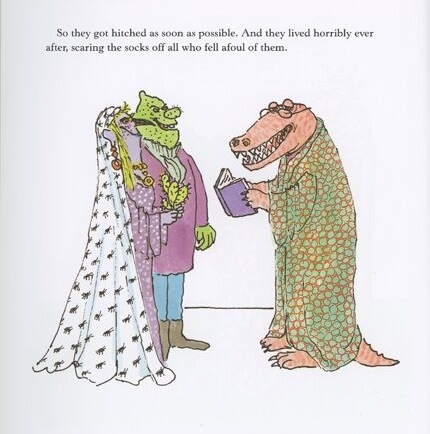

Stieg never “redeems” Shrek, or gives him a makeover, or transforms him into a handsome prince. Shrek is allowed to be what he is and look the way he does, and find happiness in his own way. Many beloved fairytales (the Ugly Duckling in particular) exhibit what Nietzche called slave morality. “You have flaws, but don’t give up! Maybe they’ll magically disappear!”

Well, sometimes they don’t. Shrek! gives it to you straight: you might have to sail the seas of life in adverse conditions. Many adult books don’t confront reality this well.

The book has zero passages describing Shrek as an ogre, by the way. He might be an extremely ugly man. Is there a “Humpty Dumpty is an egg” psyop going on where we collectively agree that he’s an ogre even though it’s not in the book? (Well, the back cover says he’s an ogre. But that’s hardly canon – authors usually don’t write their back blurbs.)

Published in 1990, Shrek! was aimed at preschoolers – although words like “blithe” and “varlet” and “churlish” and “carmine” probably caused some parents to reach for the dictionary. I like the author’s name. Stieg. All of the authors I grew up with had these ominous, evocative sounding names, usually beginning with S. Sendak. Stieg. Seuss. Shel. Stine. Names that made them sound like wizards in high towers, stirring bubbling cauldrons and summoning lightning. Surely no children’s fiction author would have a name like “Bob”.

All in all, a worthy book: Roald Dahl for kids who aren’t old enough for the real Roald Dahl. It’s well worth reading (or re-reading) while you wait for Halley’s Comet. 28 July 2061. Are you excited? I know I am. Soon.

But we still have the movie to discuss.

In 2001, commercials for a film called Shrek began rolling out. Stieg’s book? A distant memory. None of my friends had heard of it.

I saw the movie and it blew me away. I’d never imagined anything so funny, so clever, so sophisticated. This was clearly and inarguably the greatest film ever made.

I talked about it to everyone I could. I had the DVD, and spent hours playing with the special features (if you had a microphone, you could dub your voice over Eddie Murphy’s). If you were my friend and hadn’t watched Shrek, I genuinely thought there was something wrong with you.

I rewatched it in 2021, and it was unimaginably worse than I’d thought.

I hated almost every part of it: the plastic doll character design, the bad songs, the cheap pop references substituted for jokes, the “don’t judge people based on appearances!” message interspersed with cruel jibes about how short the villain is. Some computer animated films (Toy Story) have become timeless. Shrek has become ocular pollution: ugly and unfunny.

The movie seems generally well-remembered by others. I wonder how many of those “memories” occurred when the writer was 10, and if they’d survive a rewatch. I made it to the Matrix ripoff scene before mumbling to an empty room “You’re just…commenting on the fact that another movie exists! How is that funny?“

Some parts held up. The opening scene is fun and sells the movie well. There’s sharp writing at certain places (such as the Gingerbread Man sequence). The barely-disguised adult humor (“Lord Farquaad”) isn’t exactly funny but at least shows a creative team with nerve.

But nothing could save the movie from the cancerous pus-filled oozing blastoma sac of Eddie Murphy.

I laughed at the donkey as a kid. Why? He wasn’t saying anything funny. In fact, I barely understood him at all.

Well, because he masterfully created the appearance of being funny. Eddie Murphy is a reminder that much (or most) of humor is in the delivery. His cadence, vocal rhythms, and confidence are flawless, and make him seem like a comedian doing a tight five on national TV and nailing it.

But he’s saying nothing. He was like an air-guitarist performing awesome rock moves with empty hands.

Donkey: [Chuckles] Can I say somethin’ to you? Listen, you was really, really somethin’ back there. Incredible! Yes, I was talkin’ to you. Can I tell you that you was great back there? Those guards! They thought they was all of that. Then you showed up, then bam! They was trippin’ over themselves like babies in the woods. That really made me feel good to see that. Man, it’s good to be free. But, uh, I don’t have any friends. And I’m not goin’ out there by myself. Hey, wait a minute! I got a great idea! I’ll stick with you. You’re a mean, green, fightin’ machine. Together we’ll scare the spit out of anybody that crosses us.

[Roaring]

Donkey: Oh, wow! That was really scary. If you don’t mind me sayin’, if that don’t work, your breath certainly will get the job done, ’cause you definitely need some Tic Tacs or something, ’cause your breath stinks! Man, you almost burned the hair outta my nose, just like the time– [Mumbling] Then I ate some rotten berries. I had strong gases eking out of my butt that day.

Yep, that’s Eddie Murphy in Shrek. Don’t worry, they only let him blather like that for fifty minutes.

It’s clearly improv – a director sat Murphy in front of a mic and told him to go nuts, hoping for another Robin Williams’ Genie. But when the entire movie is littered with this sort of babble, it becomes grating, and then enraging.

The danger of writing a character who annoys other characters is that they will also likely annoy the audience. The 2000s were boom years for black actors with nails-on-chalkboard patter. Will Smith. Chrises Tucker and Rock. Tyler Perry alone is persuasive evidence that we need to means-test microphones before giving them to the black community.

In all, not a good movie.

But there’s a deeper level to all of this. A conspiracy, if you will. As soon as I read item 3 on this list, I heard the X Files theme playing in my head. Mostly because I was playing xfilestheme.mp3 on my computer while reading it.

Douglas Rogers (the art director) found a place there that was a magnolia plantation where he did research to get the look of Shrek’s swamp just right. It was perfect and exactly what he had been looking for, for the film.

While there, though, he was in for quite the big surprise. And that surprise was an alligator, that unfortunately, ended up chasing him.

Once again, this crew’s dedication is something else. Though, I’m sure he wasn’t expecting the alligator to run at him.

All I can say is I hope he felt it was worth every bit of running from the alligator because that is a seriously scary situation to be in all for research for work.

An alligator. In a swamp. One that’s very defensive of Shrek’s legacy. Where have I seen this before?

Damn.