Do you like to read manga? How do you keep yourself distracted from the constant gasping, wheezing sound of the art form DYING ON ITS FEET?

Do you like to read manga? How do you keep yourself distracted from the constant gasping, wheezing sound of the art form DYING ON ITS FEET?

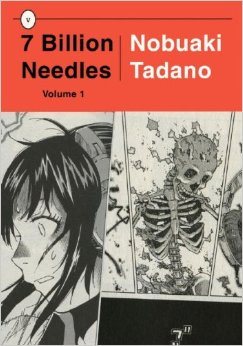

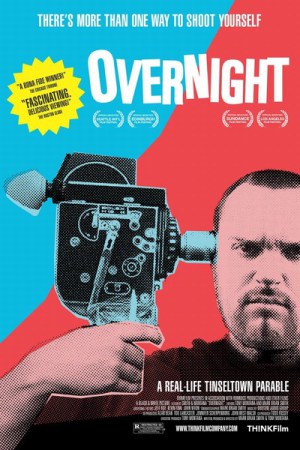

This is shit, guys. I got 7 Billion Needles in 2012. Junji Ito was in one of his periodic 2-3 year “releasing fucking nothing” dry spells, and this looked vaguely similar. What I got managed to be not what I expected via the contradictory path of being EXACTLY what I expected: cliche after cliche after cliche, hammered down with the repetition of a judge’s gavel.

This is the swill that passes for horror manga? Even a novice to the form like myself could pick up on all copy-of-a-copy ideas. “Main character fuses with a symbiote and fights monsters”? Off the top of my head: Parasyte, Variante, Tokko, and Genocyber…and I read LESS THAN ZERO manga. Main character’s an alienated high school girl? Be careful, I’m not sure Western markets are capable of handling this much originality.

The story is better recapped by someone who cares more than me (ie, anybody). The character design is workmanlike and boring. The art is full of computer-assisted gradient shading and all the other parlour tricks of a bored pen monkey cranking out a generic serial to an editor’s cracking whip. The plot has a lot of…events, you could call them. Things happen. Then they stop happening. Repeat for a few hundred pages. Launch franchise.

7 Billion Needles is apparently inspired by Needle, by Hal Clement. The storytelling is not reminiscent of any era of Western science fiction, just a very standard manga formula that’s executed neither better or worse than average, and doesn’t stand out even by being a train wreck. Cripples inspire pity: bores inspire no reaction at all.

When I think of horror manga, I think of Kazuo Umezu’s doomed worlds, Shintaro Kago’s gross-outs, Suehiro Maruo’s nihilism and aesthetics, Jun Hayami’s brutality, Junji Ito’s fetishistic HR Gigerisms…even Hideshi Hino’s primitive efforts have more panache and charm than 7 Billion Needles.

The title comes from a metaphor: the difficulty of finding a particular needle amongst seven billion other needles. This also describes the experience of anyone trying to find decent manga in this day and age.

Listening to this is like drinking from a fire hose.

Listening to this is like drinking from a fire hose.

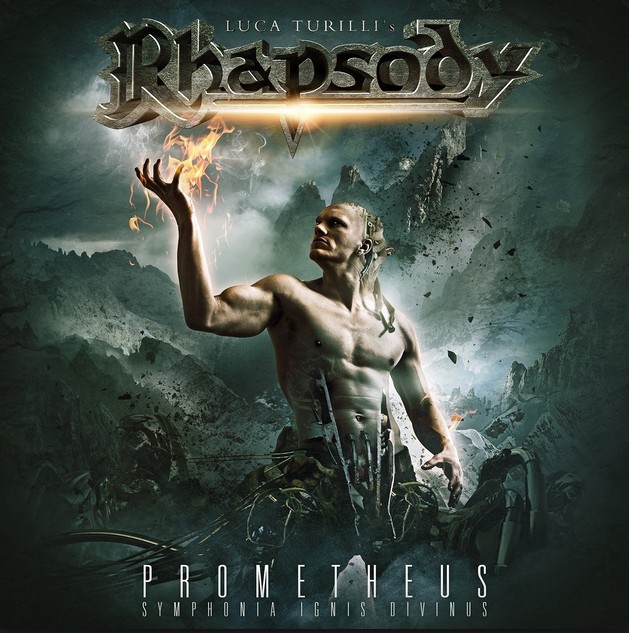

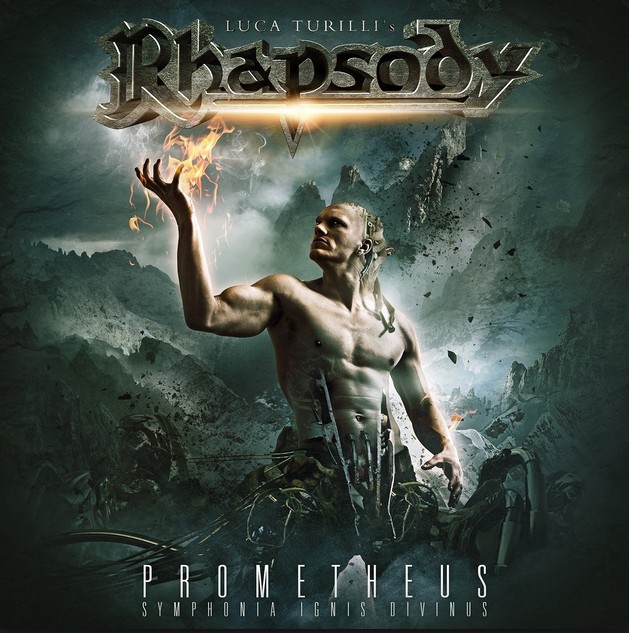

Most bands take time off, then release a batch of new songs (ie, albums). Luca Turilli works this formula on a meta level: he takes a LOT of time off, then releases a flurry of albums. He has truly pathological release patterns. Counting both Rhapsody albums and solo releases, from 2000-2002 he released three albums and one EP. Then, a few years off. Then, in 2006, three new albums. Another break. Then, from 2010 to 2012, three new albums and one EP. Now, we’re coming off another 3 year break. Have the floodgates opened again?

Prometheus is a monstrous effort, and ranks among Turilli’s greatest work. The power metal is still there, fused against an even expanded backdrop of symphonic scoring, as well as an electronic element we haven’t heard from him since Prophet of the Last Eclipse. There’s so much of…everything that it becomes overwhelming. This is musical Where’s Waldo – a short exercise in what it’s like to have ADD.

“Il Cigno Nero” is fast and breezy, a power metal song with a lead guitar tone so crisp and sharp that each note seems rimed in frost. “Rosenkreuz” and “Anahata” are slower but attack from about the same angle. Choruses are large and powerful, but layered with that distinctive Rhapsody intrigue that makes you look forward to your tenth and twelve listen, just so you can appreciate the final small details.

“Yggdrasil” sports the album’s most diverting chorus, and would have made a good lead single. “One Ring to Rule Them All” has a massive build-and-release in the prechorus leading into the chorus, as well as an appealing folk metal bridge. Final track “Codex Nemesis” is 18 minutes of the densest and most intricate music Luca’s composed to date. I think I had to listen to all the other songs twice before I felt equipped to understand this one.

There’s a lot of things this album is, and a few things it isn’t. It’s not a power metal assault like the final two Rhapsody of Fire albums. The guitars exist only as one instrument among many. It’s not really as much of a “band” effort as some seem to be looking for – I’ll take Luca’s word that there’s a guy playing bass along with this, because I sure can’t hear him in the mix. But that’s not what this project was meant to be. It was designed to push the Rhapsody sound as far in one direction as it would go.

Does it work? Listen to “Solomon and the 72 Names of God”, for example, and tell me. It’s not a question of whether the album has things to give. It’s a case of whether you’re equipped to capture it all. The nozzle of the Luca Turilli fire hose now stands before you, and someone just unkinked the pipe.

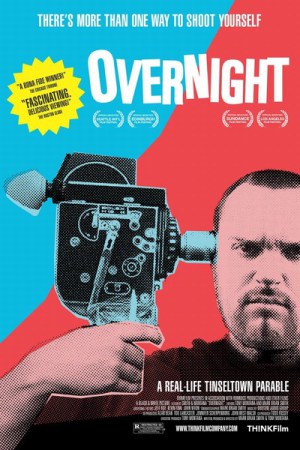

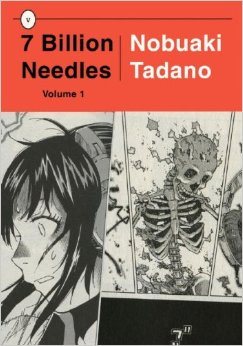

It doesn’t take much rope for some people to hang themselves. “Overnight” is a 2003 documentary about someone who hung himself with six inches of empty air. Troy Duffy was a bartender in LA with a screenplay, and he received an opportunity that hardly ever happens to bartenders in LA with a screenplay – a major production and distribution deal from Harvey Weinstein. Thrilled, he immediately hired a couple of local filmmakers to make a documentary about his assured rise to fame and riches. They ended up capturing a Hindenburg disaster on film.

It doesn’t take much rope for some people to hang themselves. “Overnight” is a 2003 documentary about someone who hung himself with six inches of empty air. Troy Duffy was a bartender in LA with a screenplay, and he received an opportunity that hardly ever happens to bartenders in LA with a screenplay – a major production and distribution deal from Harvey Weinstein. Thrilled, he immediately hired a couple of local filmmakers to make a documentary about his assured rise to fame and riches. They ended up capturing a Hindenburg disaster on film.

When aliens land and ask us for positive reasons why we shouldn’t be assimilated, I don’t there’ll be many fingers pointing at Troy Duffy. Arrogant, belligerent, with a tendency for insulting the big-name actors that he’s supposed to be schmoozing, he’s never made a movie before, and hasn’t even been to film school. He brags about showing up to production meetings hungover and wearing last night’s trousers. He has one talent: malapropism. “We’re a cesspool of creativity!” he exclaims. Elsewhere, he schools a naysayer: “Get used to my film career, ‘cuz it ain’t going anywhere.”

His boorish antics land him on Hollywood’s collective shit-list, and soon he receives a call from Weinstein. His film has been put into dreaded “turnaround” mode, halting production until a new deal can be negotiated. When a new offer to pick up the film emerges, its financing is very, very thin. And when the film is made, nobody wants to distribute it.

Another plot thread involves Duffy’s band, The Brood, who received a label deal to score the soundtrack to his film. His bandmates soon come to suspect that Duffy is not sharing his sudden windfall equally. At first Duffy says they don’t deserve a share of the royalties. Then, he moderates his position. “You do deserve it, but you’re not gonna get it.”

Things go from disaster to disaster, with Duffy’s family, co-producers, and bandmates going along for the ride (it’s not their first time dealing with this guy. You think they suspect there’ll be rubbernecking opportunities aplenty). As his projects steadily burn down, there’s endless scenes of Troy either partying or being a jackass. No doubt he fancies himself a work-hard-play-hard type, like Howard Hughes. But he hasn’t actually achieved anything yet. He’s like a runner who wants the champaign popped at the 900m line.

The documentary is fairly narrow in focus. We don’t see the critical moment where Duffy negotiates the film deal in the first place. And it doesn’t delve into the conspiracy theories about why Weinstein took a chance with Duffy, even if only for a figurative moment. It’s been speculated that he never planned to make Duffy’s film, that The Boondock Saints was destined for turnaround since day one, and it was just a PR stunt for his company. Yank a peasant out of the mud, and put a crown on his head. Then, when the cheering crowds are gone, quietly take it away. We don’t know if this is what happened. It’s certainly about as plausible as Weinstein trusting Duffy with millions of his dollars.

Ironically, Duffy’s film has proven to be massively popular on DVD. Unfortunately, he signed a contract that does not make him party to DVD profits.

Do you like to read manga? How do you keep yourself distracted from the constant gasping, wheezing sound of the art form DYING ON ITS FEET?

Do you like to read manga? How do you keep yourself distracted from the constant gasping, wheezing sound of the art form DYING ON ITS FEET?