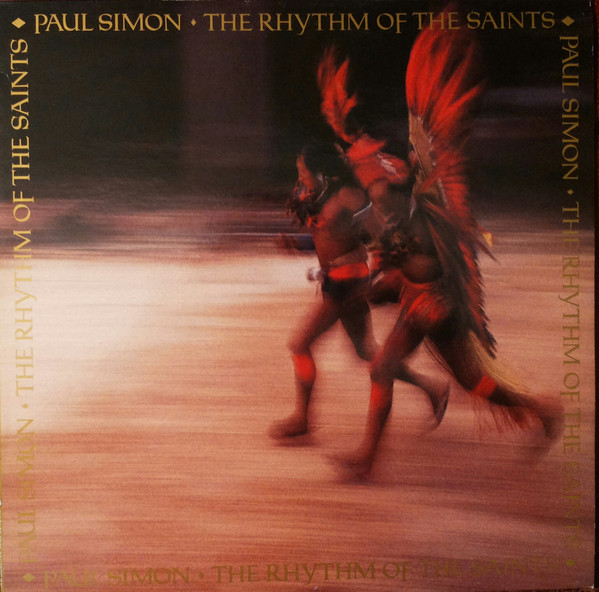

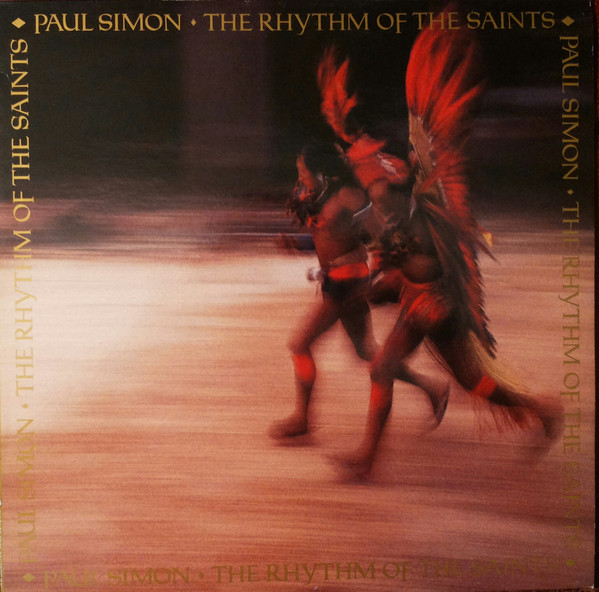

Paul Simon’s follow-up to Graceland is about 75% as good as Graceland and suffers from comparison to Graceland at every turn and here’s a fourth Graceland.

It has many excellent moments, and certainly tries hard enough to to be a big event (it’s stacked with Latin American percussion ensembles, and the production credits list a mind-numbing eighty-six names). But although it can survive being worse than its predecessor, it also can’t escape it.

Graceland, aside from being a pop monster, had weight behind it. Launched in the face of a boycott, it tackled political subjects like apartheid, racism, slavery, and classism, along with Simon’s personal issues – his divorce, his deathspiraling career, etc. It was saying something.

Rhythm of the Saints, by comparison, says little. “I Can’t Run” has a verse about the Chernobyl disaster (nearly five years in the past by then) that doesn’t fit with the rest and has apparently wandered into the lyric sheet by mistake. “Born at the Right Time” snarls peevishly about overpopulation (“Too many people on the bus from the airport / Too many holes in the crust of the earth / The planet groans / Every time it registers another birth”). “The Cool, Cool River” seems to be about environmentalism. It’s half-hearted jabs flung in every direction, few landing with much force.

And given that Graceland had sold over ten million copies by this point, Simon isn’t a scrappy underdog anymore; he’s a mega-selling music phenomenon throwing his weight around. The go-for-broke audacity of the last album is gone. Now he comes off as a rich white guy paying Brazilian drummers to spice up his pop songs.

Paul Simon never musically justifies why he’s doing this, or why he’s chosen to explore this new style. Graceland borrowed from everywhere, but it had a method to it. The intimacy and sweetness of the early Simon and Garfunkel felt mirrored in the mbanqa and township jive of South Africa – with its lavish vocal harmonies and communal aspect – and the links between slave music and 1960s folk/rock are almost too obvious to mention. It all fit together.

By contrast, the showboating tribal drumming of Rhythm of the Saints feels calculated and even cynical on Simon’s part. He’s trying to turn Graceland into a formula he can re-use again and again. “Pop songs, fused with [your country here’s]’s music”. If the cards had fallen differently, we’d be hearing Paul Simon playing guitar along with Mongolian throat singers or Malay gamelan orchestras. It’s just unmotivated exoticism.

The songs are mostly good, leaning as they do into rhythmic textures rather than singalong pop hooks. “The Obvious Child” is the obvious lead single. “Proof” hits hard. “I Can’t Run” is the best song: anxious, itchy, desperate to move but stuck in place. There’s an altered version on In The Blue Light which is also good but sad: it replaces the chicotes and castanets with an orchestral, and in doing so exposes how unnecessary the Latin American elements were to the song.

Rhythm of the Saints was commercially lifted by the aftershocks of Graceland. It shifted a lot of copies upon release (and it was soon certified double-platinum), but its sales rapidly died away. Three singles were released; all of them flopped. These are the typical signs of an album that isn’t selling on its own merits but is instead riding a wave.

I’m too hard on Rhythm of the Saints. It’s huge, elaborate, and detailed. Simon clearly cared deeply about this album, and tried to make it as good as it could possibly be. But through it all is the sound of an artist grasping and scratching to a ragged mountain peak, and finally losing his grip. He can’t help but fail a little. When you’re at the top of Everest, where else can you go except back down to the base camp?

My favorite music from 2020 is All Thoughts Fly, a forty minute instrumental album with one huge instrument raging against its walls.

All Thoughts Fly is written so that there’s room for nothing else except a quarter-comma Meantone-tempered pipe organ. A second instrument would have killed it, and vocals would have buried it. Thomas Aquinas once said “hominem unius libri timeo” (“I fear the man of a single book”). Of All Thoughts Fly he might have said “hominem unius organum musicum timeo”. It’s formidable in what it achieves with a limited set of tones: maximal miminalism. At times it’s forceful enough to punch a hole through reality, but it also attains moments of subtlety, and even sublimity. Let go of the safety rails and listen to it.

It’s inspired by Sacro Bosco, or “Sacred Grove”, a late Renaissance Italian garden scattered with huge, grotesque statues. These depict whales, bears, dragons, mythological figures, a man-eating elephant, disconnected body parts, and more. The perverse statuary is marred by cryptic irruptions of poetry. “And all other marvels prized before by the world yield to the Sacred Wood that resembles only itself and nothing else.”

The sculptor (credited as Simone Moschino) did with stone what Hieronymous Bosch did with paint, but while Bosch was motivated by faith, Sacro Bosco’s inspiration was more earthly (and sad). The park was commissioned by condottiero Pier Francesco Orsini in an act of mourning for his deceased wife Giulia Farnese, and while the precise meaning of the deranged strew of statues is lost to time; they are probably either manifestations of grief or expressions of hope: that are bigger and weirder things than man and his pathetic threescore-and-ten life, and death is not final. It’s notable that many of the monuments (Orcus, Cerberus, and Persephone) relate to underworld and the afterlife.

So what’s the album like?

It’s not classical music. The pieces are structured pretty simply and rely on force more than intricacy. There are suggestions of Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Sigur Ros, Vangelis, SUNN O))), Berlin-era Bowie instrumentals and so on. Even when classical music is hinted at, it’s closer to Phillip Glass than, say, Bach.

And then there are moments that hint at nothing, where the music sounds like nothing you’ve heard before. Von Hausswolff allows you to climb a ladder of familiarity and then kicks the ladder away. Soundscapes pulse like the heaving flank of an alien beast, the air streaming from Hausswolff’s pipes like bubbles from the gills of a fish. In reality, alien things are everywhere. Gardens are fantastical, and Sacro Bosco’s monuments are largely drawn from real, living creatures.

“Theater of Nature” begins with ripples fluttering across a tonal sea, before progressing into a sequence of four-and-five note ostinatos, puncturing the background drone in huge knife-thrusts of sound. The song is stumbles along in a 5/4 meter, capturing the feeling of the park: man’s purpose knocked astray by nature. We pave a courtyard, but plants grow through the cracks. A man marries a woman, but she dies. There are piercing treble notes that sound like synthesisers. They glide high across the rest of the sound, hints of a heaven you hope exists but cannot reach.

“Dolore di Orsini” is a keening lament from Pier Francesco ‘Vicino’ Orsini to his lost love. Very simple and pared back. All Thoughts Fly breaks things down and builds them up again, again and again, as if letting you catch your breath.

“Sacro Bosco” is one of the higher builds: big, ugly, dark, and challenging. Black gasps of air swirl out like a the breath of a steam engine. But soon the mechanical rhythm is overwhelmed by an ecstatic wall of sound; nature is falling down, falling in, eating up man and his works. It’s pretty violent, and violently pretty.

“Persephone” takes us back to minimalistic sadness. A nearly empty box, with a little lost melody wandering inside it.

“Entering” sounds like a compost of all the proceeding pieces: gathering up “Sacro Bosco”‘s noise and “Dolore di Orsini’s” melancholy and “Persefone’s” melodicism and even a reprise of the “Theater of Nature” theme, along with some beater-box percussion. The track is two minutes long and comes in and out like a wave, as if clearing the ground for the next track.

The twelve-minute “All Thoughts Fly” is high-vaulted and airy, like a cathedral. Hausswolff constructs clouds inside the space, and dashes them to raindrops. The oscillating arpeggios produce a mild hypnotic effect. This is the longest track, and the most Glassian – it was like listening to an outtake from Koyaanisqatsi at times.

The song (and album) title come from the most famous part of Sacro Bosco, the vast mouth of Orcus, the Roman god of the underworld. He was largely worshipped in rural provinces, which allowed him to survive for a time after Rome’s urban dieties fell before Christianity (it’s fitting that his most famous monument is surrounded by plants). The garden is private thoughts and feelings projected into the crudest biggest form imaginable, and the acoustics inside Orcus’s mouth mean that whispers inside are clearly heard by those outside. Hence the inscription on Orcus’s upper lip, “All Thoughts Fly”.

Sacro Bosco’s patron would have agreed that there’s beauty in largeness, and in music there’s nothing larger (or louder) than a pipe organ. They’re bestial. The biggest ones barely seem like instruments: they’re more like engineering feats akin to suspension bridges. The Boardwalk Hall Auditorium Organ in Atlantic City, New Jersey has eighteen meter long pipes weighing over a ton each, cold-rolled on machines normally used to make battleships. These immense pipes play notes so deep that they don’t even sound like notes, they’re like jackhammers or helicopters. The first time an organist hit the lowest register C, a shower of tiles fell from the roof.

They’re the most quintessentially masculine instrument, so maybe it takes a woman to wring texture and sensitivity out of them, as Von Hausswolff does on the haunting coda “Outside the Gate (for Bruna)”, which might be the album highlight.

Von Hausswolff could be described as a heavy metal musician who doesn’t play heavy metal. Indeed, her career has been marked by absurd moral panics that actual heavy metal seldom inspires anymore. In 2013, leftist groups attempted to deplatform her as a “fascist sympathizer” for the crime of wearing a Burzum shirt, and in 2021, she attracted protests and boycotts in France because of a hilariously tame reference to the Devil in her lyrics.

Her fash-symp Satanism sounds better with each new release. 2010’s Singing from the Grave, doesn’t stand out as exceptional. 2013’s Ceremony was massive and grand, though some of the “Pitchfork metal”* moments irked me. I like most of what I’ve heard from her next few releases, but here she’s delivered something truly complete and remarkable. All Thoughts Fly fills the the universe, and hints at luminous things beyond it.

(*What do I mean by “Pitchfork metal”? It’s a particular style that’s hard to describe, but bear with me. Imagine a Pitchfork writer with VERY thick framed glasses. No, thicker than that. You’re still not imagining how thick his frames are. Imagine someone with his head fully encased by a gigantic block of cellulose like an insect trapped in amber. But he has a tiny hole drilled into his immense frames, and a wire descending down to his ear. The music he’s listening to is Pitchfork metal.)

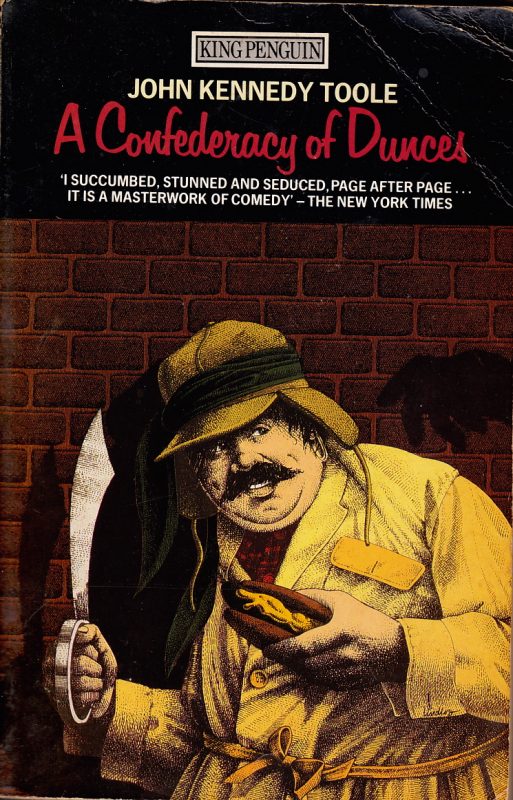

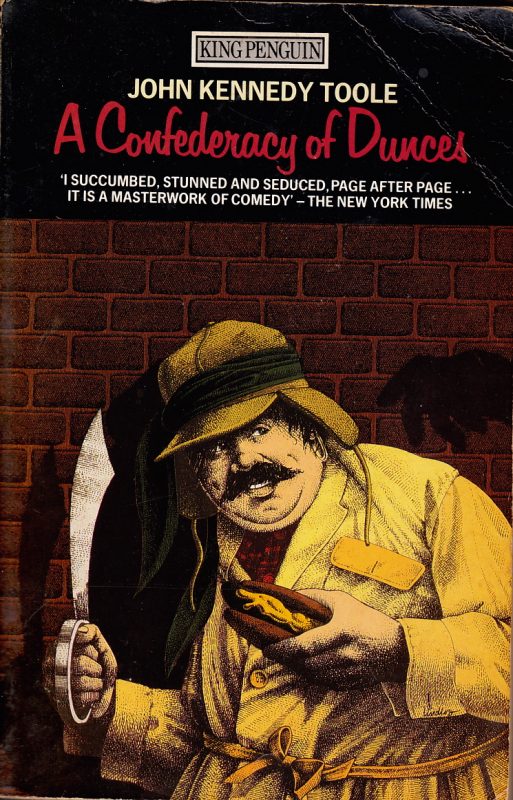

“What I want is a good, strong monarchy with a tasteful and decent king who has some knowledge of theology and geometry and to cultivate a Rich Inner Life.”

Incredible book. Maybe the funniest ever written. I dearly wish I could go back in time and experience it again for the first time.

How did Toole, a 26 year old who lived in a few places and met a few people, write a satire so sharp and cutting? And universal? You will encounter nearly every person you have ever met in A Confederacy of Dunces, and witness nearly every social absurdity. The book is a high-wattage laser focusing on excesses of human behavior until they either glow or shatter. It’s like an American version of Waugh’s comic novels: not as well-written, but funnier, moving with a lighter step, and with even more vivid characters.

The most vivid is Ignatius J Reilly, an obese, arrogant history grad who lives with his mother in 1960s New Orleans. “History grad” doesn’t cover Ignacius. Astronomers don’t want to live on Jupiter, and geologists don’t want to live in a cave, but Ignatius wants to live in the Middle Ages.

He feels a sullen, burning anger against all of modernity. He is proudly jobless (“Apparently I lack some particular perversion which today’s employer is seeking.”) and occupies himself by writing “a lengthy indictment against our century. When my brain begins to reel from my literary labors, I make an occasional cheese dip.” He is laughable, gaseous, and contemptible, the spiritual ancestor of the neoreactionaries. He offends nearly everyone he meets, although not half as much as they offend him. He feels a kinship with the “Negroes”, however, his brothers in societal oppression.

But Toole makes Ignatius sympathetic, despite his tirades and hubris. We’ve all met this guy, or been him. He’s the kid who never got invited to any parties and has decided that it’s just as well: he’s too civilized for those nasty brutes. The sadness at the heart of Ignatius’s self-delusions cause something even stranger to happen, we start to like him.

Francois Truffaut famously said that it’s impossible to make an anti-war film because the nature of film makes exciting. Literary fiction (where we can see inside a character’s head and can witness their internal logic) does the same for egomania. From the outside, Ignatius is intolerable. From the inside, his gale-force personality wins us over. He does indeed have, as he puts it, a “Rich Inner Life”.

After a car accident puts the family in debt, Ignatius is faced with the horrific fate of having to work at a job. The bulk of the novel involves him trying to do so, and failing. The actual story’s pretty thin and episodic: this reputedly scotched its chances of publication within Toole’s lifetime – it was rejected by Simon & Schuster’s Robert Gottlieb because, apparently, he saw no point to it.

But there is a point: the ways arrogance is a mask for insecurity. Everything Ignatius says and does is a rationalization for his own failures. He watches far more movies than most people do, but justifies himself by saying he’s injuring himself against “perversion and blasphemy”. When he struggles to fit into a uniform, he laments that it’s made for a modern person’s “tubercular and underdeveloped frame”. In his off-hours, he writes invective-filled letters to a young female beatnik socialist named Myrna Minkoff who he is obviously obsessed with.

Myrna Minkoff is another character who comes alive on the page, which is saying something, because we never meet her until the end. She writes long letters back to Ignatius, focusing on his physical inadequacies, sexual repression, and urgent need for therapy. Supposedly, she is based on the hyper-aggressive female activists Toole encountered while teaching in New York. “Every time the elevator door opens at Hunter [University], you are confronted by 20 pairs of burning eyes, 20 sets of bangs and everyone waiting for someone to push a Negro.”

She is the opposite of Ignatius politically, but his equal at deluding herself. She’s putting on a play about interracial marriage, and has forged links with the female black co-star. “She is such a real, vital person that I have made her my very closest friend. I discuss her racial problems with her constantly, drawing her out even when she doesn’t feel like discussing them — and I can tell how fervently she appreciates these dialogues with me.”

There are other characters: a couple of ess-doubleyous at a French Quarter strip club, some gormless souls at a family-owned jeans factory, a bumbling police officer, etc. They are interesting on their own but become dim shadows when set against Ignatius and Myrna.

The book is famous for its detailed depiction of New Orleans. I always dislike it when reviewers say something like “the city’s almost like another character!” Cities are cities and characters are characters. An urban environment doesn’t have to be a person to be interesting, that’s just anthropomorphism. But New Orleans – the patois, the heat, the culture-clash – is an inseparable part of why Confederacy works. Whenever the action threatens to get a bit too ridiculous there’s always that anchor to pull it back to reality – this sense that it’s in a real place that actually existed. Little details, such as the daily life of a hot dog vendor, are rendered in believable accuracy.

The best part? The dialog. Confederacy is possibly the most quotable book ever written. I can recite large sections of it from memory.

“I mingle with my peers or no one, and since I have no peers, I mingle with no one.”

“In my private apocalypse he will be impaled upon his own nightstick.”

“Do I believe the total perversion that I am witnessing?”

“If you molest us again, sir, you may feel the sting of the lash across your pitiful shoulders.”

“This liberal doxy must be impaled on the member of a particularly large stallion!”

“Go dangle your withered parts over the toilet!”

And so on. The book’s a ridiculous caricature, but like a caricature, we recognize everything it. Forty years after it was published, the book still seems eerily accurate to how people think and behave. Maybe life is more limited than it seems: its complexity spun out of a few repetitive people and scenarios, just as a jewel’s intricacies can be understood from seeing a single facet. Either way, when Confederacy of Dunces reaches its disastrous end, you’ll want Ignatius to prevail in his one-man war against the modern world.