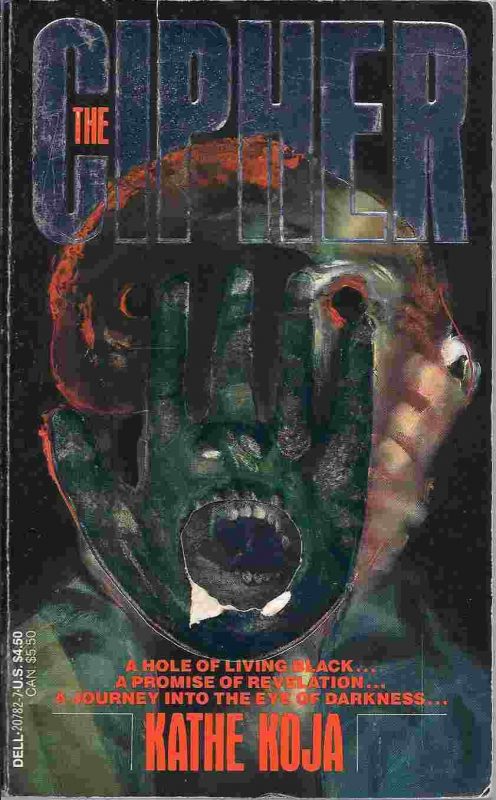

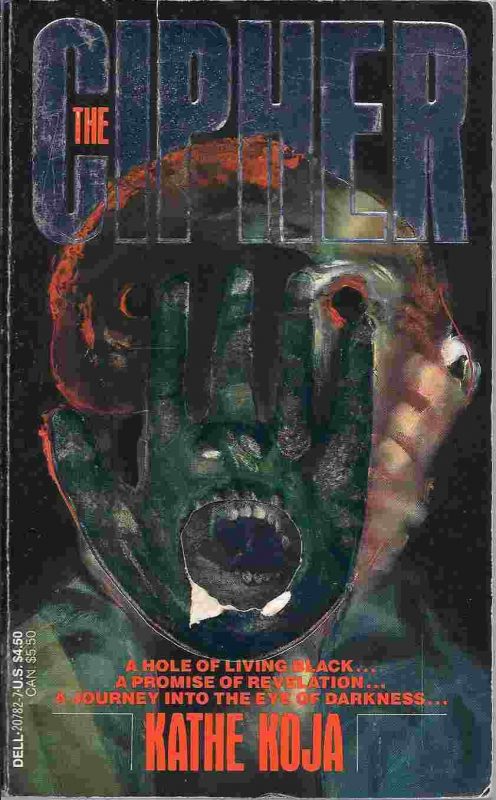

Horror novels have a shelf life of forever or five years, whichever comes first. Kathe Koja’s first novel The Cipher was published in 1991, won the Locus and the Bram Stoker, was critically acclaimed as a major work of the genre…

…and then went out of print for thirty years.

It has a sharp premise. Failed poet Nicholas (and his codependent girlfriend Nakota) find a black hole in storage cupboard. They begin dropping things into the hole on a string. Bugs grotesquely mutate into chitinous aberrations. A dead mouse turns into a Jurassic horrorshow with claws twice the length of its feet. Then they lower a camera into the hole…

The Cipher belongs to the micro-genre of “hole fiction”, which includes Stephen King’s From a Buick 8 and Junji Ito’s The Enigma of Amigara Fault and others I can’t recall. A fracture appears in reality; one that cannot be understood, only experienced. Things transform when they pass through it. The “holes” in these books are never actually holes, they’re a metaphor for some writerly stalking horse (the unexplainable, death, and so on). Early on, Nakota makes the observation that the Funhole (as they call it) only becomes active when Nicholas is around it. Why would this be true? What’s special about him?

Koja’s prose is striking. Her patented “kill all verbs” style shatters sentences into oblique, slanted observations, which collectively pile up into scenes, action, etc. Koja’s sentences are frag grenades, in both senses.

We waited quite a while, there in the dark, my back against the locked door, Nakota for once at my side. Her scent was higher, her breath never slowed; she tried to smoke but I told her no, not in that airless firetrap, firm whisper, as firm as I ever got with her anyway, and she gave in. The insects jumbled, up and down, fighting the barrier they couldn’t see, then, “Look,” her sharp whisper but I was looking already, staring, watching as the bugs, one by one, began to drop, dying, to the floor of the jar, to whir in minute contortions, to, oh Jesus, to change: an extra pair of wings, a spare head, two spare heads, colors beyond the real, Nakota was breathing like a steam engine, I heard that hoarseness in my ear, smelled her hot stale-cigarette breath, saw a roach grow legs like a spider’s, saw a dragonfly split down the middle and turn into something else that was no kind of insect at all.

Koja, more than any author I’ve read, writes the way people see. We perceive vision as continuous, but it’s actually made up of thousands of micro-adjustments called “sacchades”. We flick from thing to thing, and gradually a picture of our surroundings emerges. It seems instantaneous, but it’s more like a painter’s process. One brushstroke. Two brushstrokes. The Cipher’s style is an effective evocation of this process.

The setting’s a grimy urban environment, with dirty snow, broken central heating units, rust, and dying video stores. Koja’s big on art in all its forms, and stuff like cinema and sculpture appear in the story, to varying impact.

Not all the story choices work, and The Cipher ends up being more good than great. After some fantastic early scenes, the momentum falters. A couple of new characters get added who don’t seem particularly relevant but succeed in padding the book out for another 100+ pages. The problem with elegant concepts is that it’s hard to get a novel out of them. The Cipher would have hit harder as a novella. As it stands, it has a stretched quality. Like a 4:3 video stretched to 16:9, or a 45rpm played at 33rpm.

edit: I have since learned that The Cipher was adapted from a work of short fiction, which makes sense.

The shocks (which are initially powerful) become increasingly broad and heavy handed, and verge on comical at a point. There’s moments in the book that read like a Chucky screenplay. They don’t ruin things, but the narrative felt like it needed a subtler hand at times.

Koja’s later work is more confident. Bad Brains shows the umbilicus chaining artistic ambition to madness (and vice versa). Skin documents a world of metal and gears where carbon-based lifeforms fear to tread. But The Cipher has its own charms: it’s very visual for a book, and would work well as a movie. Ironically, because Nicholas is doomed from the moment he begins filming the Funhole.

1999’s hottest craze next to school shootings is back with their second album and they’re still abominable. Slipknot might be the Coldsteel the Hedgehog of bands, but I’ll make the best case I can for them here: they are entertaining. I will never sit through a Coal Chamber album, and any scenario where I listen to Papa Roach will involve a CIA black site and the words “we have ways of making you talk.” But I occasionally listen to Slipknot.

What’s changed? Well, they toned down the wigger moments. Only one song (“I Am Hated”) has rapping on it, though Corey Taylor amps up the cringe by using a Vanilla Ice stress pattern. You know the one – where the rapper emphasises the last word of every line. “The whole world is my enemy, and I’m a walking TARGET / Two times the Devil with all the SIGNIFICANCE”. Why doesn’t Suge Knight dangle this jackoff out of a hotel window?

Instead we get extra helpings of noise and incoherence, sixteen drummers playing over the top of each other instead of fifteen, putrid clean singing, and more trendy modern shit like record scratches. The songwriting is horribly loose – half the time the band seems to have no idea what they’re doing. The guitars just chug aimlessly while endless snare and tom flurries roll over you, and then the song ends because a record label exec held up a “stop playing now” sign in front of the recording booth.

The band does okay when they keep things tight and interesting. “Left Behind” is quite good, though its melodic approach makes it stick out. “The Heretic Anthem” has energetic moments and a fun chorus. “Disasterpiece” starts well but then just becomes more shit by the end.

Iowa‘s pretty funny: almost a comedy album, in fact. Was this intentional? Do I look like I care? It’s impossible to hear the opening few seconds of “Everything Ends” without laughing, and “People = Shit” is hilarious throughout. Again, Coldsteel the Hedgehog.

But it’s also dull. Incredible dull. Reigning back the cartoony Fred Durst antics was a mistake: the silly stuff was the stronger side of Slipknot: it’s like if Tommy Wiseau released a director’s cut of the Room with “you’re tearing me apart” removed. Here we see the beginnings of their bland latter-career sound, culminating in All Hope is Gone, which might be the most boring album ever made. “Skin Ticket”, “The Shape”, “Metabolic”, “My Plague”, “Gently”, “New Abortion”…all garbage from beginning to end.

Iowa ends with…uh…”Iowa”. Fifteen minutes long. Great. Finally, they gave us the Dream Theater-esque prog nu metal epic the world has been clamoring for. I have nothing to say about this song, except that it’s unlistenable. It drones and goes nowhere and spends forever going nowhere. It sounds like they took every bad part from every bad Slipknot song and slapped them together, back to back. “Iowa” isn’t music, it’s nu metal writing a suicide note.

Why is the album called Iowa? Yeah, the band’s from there, but you don’t see country singer Kelsey Waldron releasing an album called Monkey’s Eyebrow. I’ve long suspect that Iowa isn’t actually the title, it’s a disability sticker. It’s like Roadrunner Records is saying “Go easy on this band, they’re from freaking Iowa, dude.” I don’t know much about the state, but based on the news stories I could find (A swimmer was infected with a brain-eating amoeba after visiting at an Iowa beach) Slipknot has clearly overcome great adversity to get where they are. I salute them, and will commemorate their achievements by playing Metallica instead.

“Lonely dissent doesn’t feel like going to school dressed in black. It feels like going to school wearing a clown suit.” – Eliezer Yudkowsky

Nobody wants their entertainment to surprise them. Musicians that change genre usually kill their careers (unless it’s a very slow, stage-managed, and natural shift between two adjacent styles). On Goodreads, it is a criminal offense for a book to differ in any way to what the reader expects, punishable by 1 star and gifs of Robert Downey Junior rolling his eyes. “Ugh, the cover made this look like queer neurodiverse BIPOC dystopian YA, but it’s actually aro/ace instead. Do better.” The world is full of thumbsuckers who want to be comforted with the familiar. The idea that art might sometimes confound or surprise is foreign to most of them.

Even “countercultural” art is confined by audience expectation: noncomformists that all dress the same, striking rebellious poses inside tiny prison cells. Marilyn Manson is often classified as “shock rock”. He has released ten albums and counting of distorted guitars, industrial samples, and Middle America baiting lyrics, and I just can’t wait to see how he shocks his fans next.

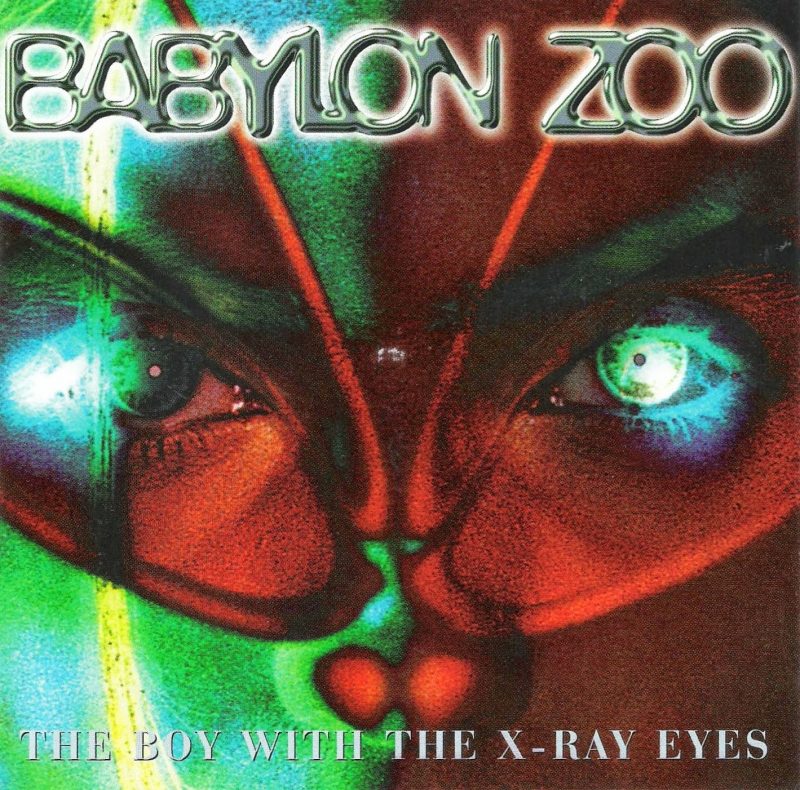

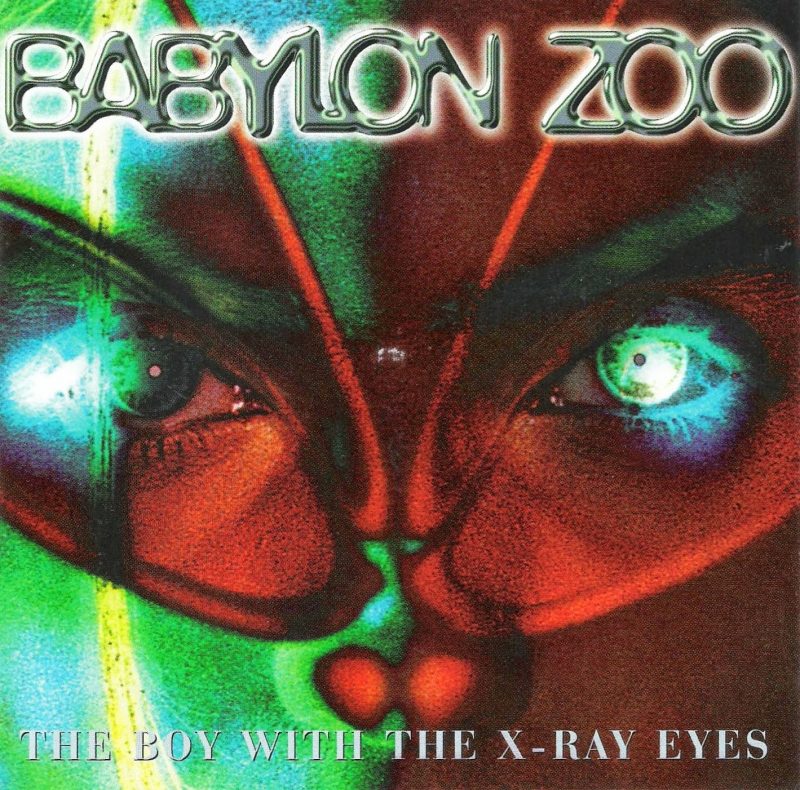

Babylon Zoo is a cautionary tale of what happens when a band genuinely defies expectations. It isn’t pretty.

They were a rock band from Wolverhampton, fronted by Jas Mann, who had just left his previous project, the Sandkings. Their style was a modern fusion of 70s glam rock (Mann’s wavering snarl is an attempt at Marc Bolan) with 90s grunge. A brilliant idea. So brilliant that Smashing Pumpkins had already gotten there first, along with many other bands.

Nevertheless, they scored a lucky break in 1995 – Levi used their song “Spaceman” for a TV commercial. The concept was fun in the way that British ad spots often were: an alien girl (played by Kristina Semenovskaya) returns from a trip to Earth, and shocks her conservative alien parents with the ultimate fashion statement – a pair of Levi jeans.

The ad got Babylon Zoo’s music in front of millions of people…except it didn’t. The ad didn’t use the album version of “Spaceman”, it used an Arthur Baker remix that sped up the track, muted the guitars, and pitchshifted Mann’s vocals upward into an ethereal whisper of ice. It was a bright, futuristic sound, congruent with the ad campaign.

However, it sounded nothing like the actual song. The thousands of clubbers and ravers that bought the “Spaceman” single soon discovered that Babylon Zoo played turgid grunge rock, impossible to dance to. The Boy With the X-Ray Eyes held more of the same. Much more.

Once the summer of 1996 was over, so was Babylon Zoo. The couldn’t follow up “Spaceman”, and subsequent singles landed increasingly far from the top, as though fired by a marksman who drinks a double vodka soda between shots. Their second album album King Kong Groover (first single: “All The Money’s Gone”) sold just 10,000 copies, and then they were dropped from EMI.

Jas Mann was the first British-Asian to top the charts (2nd, if we count Farrokh Bulsara), and most of the publicity focused on him. It must be said that he handled his sudden fame sub-optimally, bigging himself up in the UK press (“I was expecting this success […] A racing driver knows when he’s got the best car – and I know I’ve done something that’s far superior to most things out there. […] I’m a great songwriter and I could become a musical genius.”), and making a Brass Eye appearance where Chris Morris ran circles around him and baited him into saying silly things.

Bowie always had a tight command over his public image – adopting disposable personas, then killing them when they threatened to consume him. Mann just came off as a callow youngster, trying to blast off into space with matchstick heads and a bottle rocket.

Babylon Zoo quietly ended, and Mann left the public eye, moving to an ashram in India. He now works in film. His main creative work these days might be this IMDB bio, which contains possibly the most lie-filled paragraph written in the English language.

“In 1996 Jas developed a visual/music project “Babylon Zoo”, writing and selling the concept to “Levis” as a visual and music advert broadcasted in over 30 countries. The first Babylon Zoo Album “Boy with the X-ray eyes” would go on to sell 5 million copies and achieving 21 number one hit records worldwide at the time entering the Guinness book of records as the fastest selling record of all-time

All false. The band formed in 1992. “Spaceman” was released as a promo CD by Warner Bros in early 1995, and then as a single on CD/vinyl/cassette by EMI. The Levi’s commercial happened afterward. It’s improbable that Mann (a 24 year old from Wolverhampton) had any creative control over the ad.

Five million copies sold in the UK? No. In 1996 the BPI certified the album gold, which meant it shipped (not sold) 400,000 copies in Britain. Perhaps it sold five million worldwide? Still no. Let’s assume for argument’s sake that the figure now stands at 599,000 (just under the 600,000, the level required for a BPI platinum cert). Are you telling me that Babylon Zoo, a UK band famous for a UK TV commercial, only moved (at most) 11.98% of their total units in the UK? Not a chance. This album shifted a million copies worldwide, max.

21 number one hit records where? Tuvalu? “Fastest selling record of all time?” Again, no. “Spaceman” is the fastest selling debut record of all time (according to this 1996 Billboard Issue), selling 420,000 copies in its first week. Band Aid’s “Do They Know It’s Christmas” sold over a million copies in its first week in 1984.

Revisionism aside, The Boy With the X-Ray Eyes was definitely a victim of success. The gap between what it seemed to be and what it was proved too big to bridge, and the chasm swallowed the album, the band, and its creator alike.

But what if you listen to it on its own, and ignore the hype?

It has strengths and weaknesses. The production is raw enough to bleed. The entire album sounds like it was barely mixed – the drums are boxy and fake, the guitars are just a harsh SKRONK that’s somehow thin and overpowering at once. Jas Mann’s vocals are a tough sell, a weak and untrained sneer without any real tone. There’s precedent for this kind of through-the-nose singing in grunge (it’s not like Billy Corgan is vocalist of the year), but the album sounds like he tracked it while suffering from a head cold.

Around half the songs are uninspired or bad. “Animal Army” is dreck, a riffless, hookless alt rock song that sounds like a Dynamite Hack 45RPM played at 33RPM instead. “Confused Art”? I’m not confused at all, the song sucks. “Zodiac Sign” is distinguished only by its irritating chorus. “I’m Cracking Up I Need A Pill”? I’m Cracking Up I Need A Skip Button.

And that leaves a number of songs that are actually listenable, or well thought out. “Fire Guided Light” is a clear stand-out track, with moody verses and an explosive chorus. “The Boy With X-Ray Eyes” has quite a bit of dynamic contrast and some densely layered instrumental, including Indian santoors and sitars. “Is Your Soul For Sale?” has a cringeworthy intro that exposes how weak Mann’s voice is (“…we dahhnced the nahhht awayyy”) but it ends up being quite good.

The story of Babylon Zoo is not that of a band (or “visual/music project”, in Mann’s own words) that was a complete waste. It only adds tragedy to the comedy, but there was actually something here.

(NB: “N-rays (or N rays) were a hypothesized form of radiation, described by French physicist Prosper-René Blondlot in 1903, and initially confirmed by others, but subsequently found to be illusory.”)