It’s an cruel lottery, becoming famous for being bad. For every Tara Gilesby there’s a twenty year old woman scrubbing the internet of her thirteen year old self’s Dramione mpreg femslash drabblefic, praying none of its readers made a copy. For every Cats there’s a very real tortoiseshell positioning its anus uncomfortably close to my face as I type this. And for every Neil Breen there’s a Charles E Cullen, who directs loosely-described “movies” that inflict accurately-described “brain bleeds”.

Killer Klowns from Kansas on Krack is about two unemployed clowns who get hooked on crack, kill people, and live in Kansas. You have to go into this movie with the right expectations. Does it have the biggest budget or the best actors? No. But is it a blast of campy B-movie fun, made with enthusiasm, passion, and heart? Also no.

Everything about it is wrong, even the title. Killer Klowns on Krack would have been dumb but punchy; adding from Kansas makes it too wordy and ruins the pun. There’s no organization called the KKKK. Cullen apparently believes that titles are funnier with four Ks than three Ks.

KKfKoK is filmed on a consumer-grade hand-held camera by a person who’s clearly drunk, although no drunker than you’d have to be to watch it. It’s very much a shoot-using-whatever’s-lying-around kind of film, with production values six levels below “indie movie”, and one level above “two kids making a movie in an afternoon”. It looks incredibly cheap. Kudos to the coin from behind a sofa cushion for financing the film, the year 1994 for providing the video editing software, and Cullen’s film school degree for not existing.

Honestly, he’s kinda brilliant, and I think big studios could learn some tricks from him. Why construct a “set”, when you have a perfectly good “trailer park”, just ready to use? Why waste time on a “second take” when you have a perfectly good “first take”? Why hire “actors” when you have a perfectly good “people who aren’t actors”? Why be “sober” when you have a perfectly good “drunk”?

It’s never clear what parts of Killer Klowns are supposed to be bad. When the camera skews queasily, is this a Dutch Angle, or did the director’s hand slip? When the footage cuts to black and white for no reason, is this the director’s attempt at mood, or did he accidentally punch the B&W button on his camcorder?

Cullen has talents aside from directing. For example, he’s also a puppeteer. I guess? I’m not sure I want to understand what this thing is, but I believe it’s a puppet.

But wait, there’s less! Cullen’s also a musician. His metier is soulfully-sung country, as shown in the song “Fading Into The Light”. “Corndogs for breakfast / Tuna for supper / Boredom at sundown / Pepsi with uppers.” I hope you enjoy this song, because it drowns out the dialog whenever it appears, which is about seventeen or eighteen times.

He’s a mime, too. How do I know that? Because of this sequence, which has nothing to do with anything and is spliced into the movie despite having nothing to do with anything. I doubt even Cullen can explain why it’s there.

Despite his obvious talents, Cullen flies too close to the sun near the end, which involve extended shootouts between krack-addicted klowns and the bounty hunter hired to kill them. It’s just a confusing pileup of people flopping around on the ground for no reason and firing shotguns one-handedly.

Here he’s clearly trying to make a bad movie, and that’s boring. Anyone can make trash: the secret to a successful bad movie is to make trash without intending to. The Room isn’t funny because of “you’re tearing me apart, Lisa!“, it’s funny because that line was meant to hit emotional paydirt. That critical lack of self-awareness is often missing from Killer Klowns.

My favorite bits are the accidental mistakes. One subplot involves a sleazy cult leader making cold calls and scamming people. But we see his computer screen…and it’s 9:52PM. That one moment – a cold-call marketer drumming up business at two hours before midnight – made me laugh harder than all the deliberately crappy special effects combined.

Cullen’s not famous – yet. The world’s not ready for his genius. One day, when he achieves mass success and is being watched by millions of people, I will be there to bask in the glory, because I believed in him. I have a sneaking suspicion that the “millions of people” will be primetime news viewers and his name will be followed by those of the 20-25 people who were in AR-15 range when he finally snapped, but still.

I highly recommend Killer Klowns. It’s not really an ironic bad movie. It’s more an audiovisual experience for when you don’t want to put any effort into watching a film but still want to experience pixels floating on a screen as your brain shuts down. It’s a 2:00am movie, in other words. I like to stay up late, playing this on repeat. My lower lip hanging slack, drooling. My mind completely blank of any thought. It’s hard to explain, but when I enter this state I almost feel like I’ve achieved a psychic oneness with the people who made it.

Paintings are dead. The oleaginous purples of baroque: dead. The petal-like brushstrokes of impressionism: dead. The apotheotic ecstasies of romanticism: dead beyond dead. Even when they evoke or suggest life they aren’t life, and if you try to breathe the unending skyful of air in Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea you will suffocate and also become dead.

Airless Spaces (from 1998) is about that kind of dying: trying to sustain yourself on artifice and illusion. It’s short – about a hundred and fifty pages – and very readable, containing fifty vignettes drawn from the author’s experiences in mental hospitals.

Shulamith bath Shmuel ben Ari Feuerstein was an early radical feminist. Her 1970 book The Dialectic of Sex launched her to fame, and it seemed like she was set for the same sort of life Greer, Friedan, and Steinem had – forty or fifty years of teaching, consciousness-raising, fighting the patriarchy a little, fighting other feminists a lot, and the occasional bra-burning publicity stunt to remain in the public eye.

Incredibly, the book marked the end of Shulie’s career. She disappeared from public view in 1971 – to pursue a career as a painter, she said. In actuality, a shadow had fallen on her, and her struggles with schizophrenia (worsened by the death of her father and the apparent suicide of her brother) caused her to be repeatedly institutionalized. Although I don’t think her name even appears in the book, Airless Space is her account of those 28 missing years.

It describes places that aren’t real places, relationships that aren’t real relationships, and words that have no meaning. Like paintings, these artifices vary in their details. Some are crude and clumsy. Others are painted with a maestro’s touch, and cleverly deceive you into thinking they’re real. But they’re all pitiful facsimiles of the real thing, and none of them are of much use at sustaining life. Like eating an apple made of wax.

There’s no theory or politicizing, instead there’s endless and fascinating detail about daily life in the land of the mad. Time is absent from the book (most stories could take place anywhere from 1971 to 1998, with only a few being dated by details like VCR and email), yet also omnipresent. The hours crawl like a broken-backed cockroach. Eventually you stop even feeling bored: you just stare slackmouthed at the clock as it sweeps from breakfast time to lunch time to dinner time to bed time.

Society doesn’t deal with insanity that well in 1998 or any other year. In most of the stories Shulie could be at a prison; she encounters rigid and unbending bureaucracy, orderlies who apparently moonlight as nightclub bouncers, and institution-fostered drug dependencies. The chapter titles alone are grim. The Forced Shower. The Prayer Contest. Bedtime is the Best Time of the Day. Bloodwork. The Sleep Room. Incontinence. The Jump Suit. Hating the Hospital. Suicides I Have Known.

There’s a section simply titled losers. The term sounds sophomorically cruel, like what a bully would say as he gives you a bogwashing, but it’s an accurate description. The people Shulie writes about have lost. There’s no other way to put it. You feel pity reading about some of them.

- Ana, a vain woman who has managed to sneak in a stylish white jogging suit. She wears it along with a face of stolen makeup, lording over the other patients “like a queen in haute couture”. Inside, she’s unimaginably glamorous. When she’s released, she looks exactly like what she is: a person sprung from a mental ward.

- Jane, a “small and ugly” punk rocker who spends her entire day on the phone, trying to get out. One morning at breakfast, each patient receives a banana, and Shulie is missed. She sees Jane not eating hers, asks if she can have it. Jane has an explosive psychotic episode, spitting in Shulie’s face while screaming an “incomprehensible torrent of abuse”. She spents the rest of her stay trying to have Shulie arrested.

- Ellin, an intelligent, cheerful, and apparently sane woman committed for hypochondria. None of the doctors believe her to be sick. Her brother suing for ownership of her property, on the basis that she’s crazy (as proven by the fact she’s in an institution). She’s spending all of her savings on lawyers to fight him and will soon be penniless. Later, Shulie learns that the brother won, and Ellin was evicted from her own apartment. She never learns what happened to her after that.

- An anonymous woman (who might be Shulie herself) hears about someone dying one day, and wishes she could trade bodies with that person. They would get a healthy body with many more years of life. She would get a dead one with no more years. This seems optimal for both of them.

- Stanley, an old friend of Shulie. He’s perennially broke ex-academic who has spent nearly every spare moment of the past eight years working on a thousand-page long magnum opus on philosophy. He submits it to a press owned by a “prominent former radical”. It’s rejected, on the basis that it’s unreadable and also they don’t do philosophy. He has no idea what else to do with it.

And so on. Along the way, Shulie gives advice on how to get out of a psych ward. Behave. Attend all activities religiously. But don’t allow yourself to become invisible, or you’ll be forgotten. Rock the boat in small ways. Stand out. Wear an interesting item of clothing if allowed. Put effort into your appearance. Pace the halls, so people can’t escape the fact that you’re there. Learn the names of all the doctors and orderlies and have interactions with them – even if it’s just saying “hello” in the hallway, and even if you’re ignored. The basic idea is to be present. There’s a world of difference between a person in an institution (who doesn’t belong), and an institutionalized person (who belongs very well), and your job is clearly be the former, so you can hopefully get out.

But out is in misspelled for a lot of people. Another sad aspect of Airless Space is that many of these people will live awful lives no matter where they are: they’re poor, crippled, will never be “better” in any meaningful sense, and their insanity is a response to circumstance (“Just because you’re paranoid, does not mean they’re not out to get you”). I’m struck by the story of Mrs Brophy, who views her prolongued hospital stays as a vacation from the nerve-shredding job of caring for her large household with many children. Another repeat in-and-outer adapts to the point of being nonfunctional in the real world. “Every time she went in, especially after the first, she felt submerged, as if someone were holding her under water for months. When she came out she was fat, helpless, unable to make the smallest decision, speechless, and thoroughly programmed by the rigid hospital routine, so that even her stomach grumbled on time, at precisely 5 p.m.”

There are some humorous touches. There’s a plane trip where Shulie complains about the in-flight movie “Melanie“, which she calls a “pre-adolescent fantasty with a decidedly lesbian tinge”. Shulie should have been a film critic. There’s also an interesting meeting where she meets none other than Valerie Solanas, whose later life makes Shulie’s look like a success story. Solanas has read The Dialectic of Sex and hates it, and starts arguing with Shulie about it. The low comedy of two destitute madwomen debating the theory of a world that rejected them decades ago isn’t lost on her.

In short, very interesting, very sad, very effective. This ain’t it, chief became Twitter’s favorite put-down for a while, and that’s what this book is: this ain’t it fifty times in a row. I don’t know that I’ll ever re-read Airless Spaces, but it made an impression. The book opens on one of its most memorable image: you’re aboard a sinking ship…but that ship is inside the Bemuda Triangle. If you’re dying in a place that’s false and unreal, are you really dying? Whatever the answer, you’re clearly not living.

In ’42, German forces advanced into Russia in the depths of winter. They were confident, thinking their foes weak and in retreat. They were about to be destroyed.

This was 1242, when a young Russian prince lured an army of Teutonic knights and Estonian auxiliaries onto the frozen surface of Lake Peipus and slaughtered them on the ice. Alexander Nevsky’s victory is remembered in Russia as Ледовое Побоище, or Icy Massacre, and might be history’s only naval battle to not involve a single boat. It ended the Teutonic Order’s pretensions upon Novgorodian territory and turned Nevsky into a national hero, sainted in 1547.

Heroes never die. Even when they pass away, something of their essence remains in the national heartwood, inspiring others through the centuries. Seven centuries after Nevsky died, history began to loop back on itself. A prisoner in Germany wrote a book about the future. He was ambitious; mad. He wanted Europe in flames, and a German empire atop the bones of a Russian one. Eight years later that man was both free from prison and Chancellor of Germany. Armies were gathering, and Russia needed heroes once again.

It was inevitable that a film about Alexander Nevsky’s life would be made: a Russian patriot fighting German Catholics was a perfect propaganda coup. Also, Nevsky had died a very long time ago, and we don’t know much about him as a person. This allowed a director freedom to “interpret” him as whoever they wanted, as well as freeing him from troublesome contemporary politics (unlike the Russian generals who had fought Napoleon…on the side of the tsar).

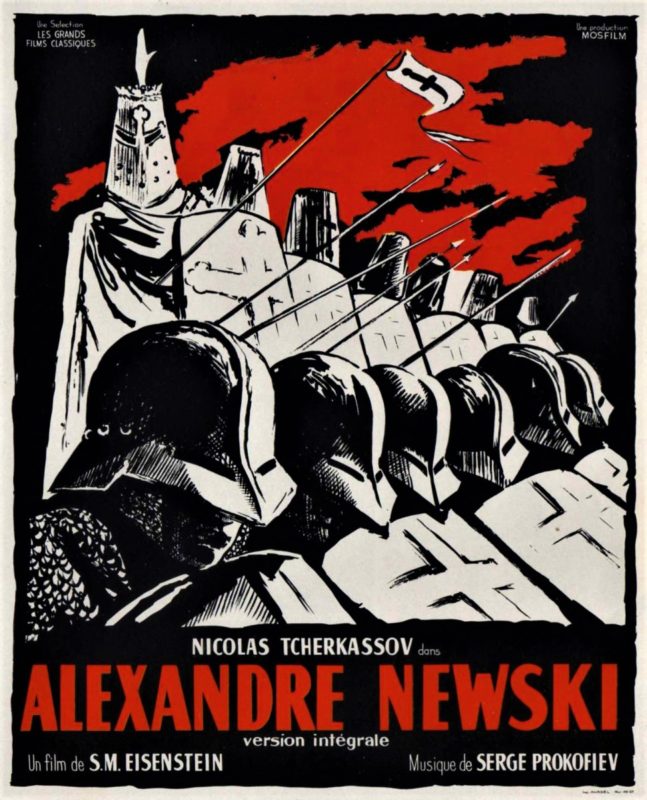

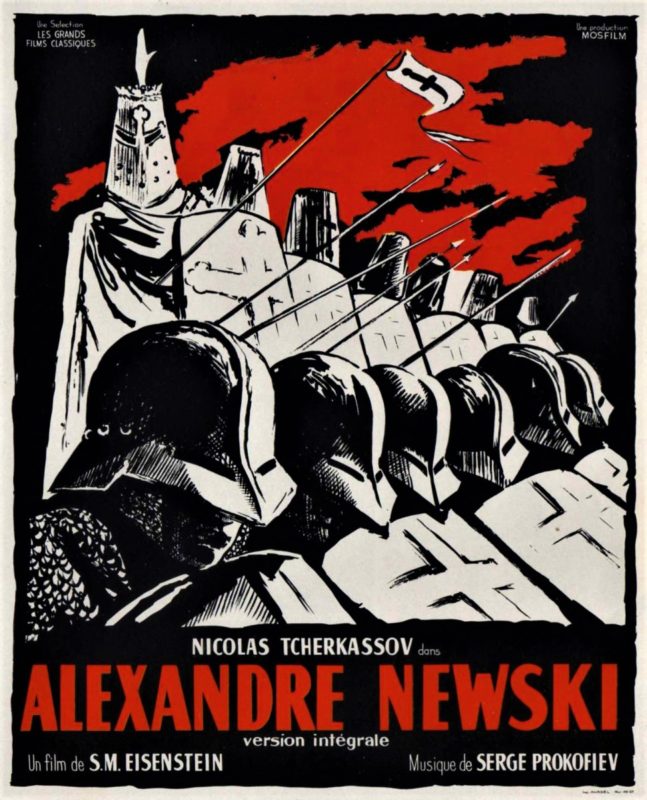

Alexander Nevski was directed by Sergei Eisenstein, with many asterisks and scare-quotes around “directed”. Soviet culture regarded artists as civil servants; if you could write a poem or paint a picture you were expected to do so for the state (and under the state’s supervision). Eisenstein was regarded as suspect when he made the film: he’d spent years living in the west, only returning after what appears to be blackmail. His previous film Bezhin Meadow had failed and earned him a public reprimand. His friends were being arrested, and he soon suspected that the NKVD was shadowing him. Eisenstein probably saw Alexander Nevsky as his last chance, and resolved not to put a single foot wrong. It’s debatable to what extent it’s “his” movie.

It was filmed in 1938 and produced by Mosfilm, with the final cut receiving some additional tinkering by the Party. You could almost give Joseph Stalin an editing and production credit. The picture gained final approval from the State Committee for Cinematography and was released on December 1938, although it hit a snag when when the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact turned Russia and Germany into momentary allies. Ultimately it was a success, rescuing Eisenstein’s reputation and gaining him a new following abroad. It’s a huge, huge film. Irrefutably part of the canon.

But is it good? Difficult question. As journalist Chet Flippo said after seeing a Queen concert, it “got the job done. I’m just not sure what the job is.”

As a movie it’s a disappointment, featuring rancid acting, a dull story, and sententious touches (medieval Teutons that wear swastikas) that turn its historical setting into chopped liver.

It’s a relic from a bygone age when film was theater’s little brother: get ready for ponderous cinematography, pounding melodrama, shouty brow-furrowing performances, and a total lack of subtlety. Your enjoyment of Alexander Nevski depends on whether you think shots like this are dramatic or silly.

Nevsky is played by Nikolay Cherkasov, whose impression of a wooden board is second to none. His acting skills are suffocated by the role he’s playing: he’s Alexander Nevsky, Great Hero of the Motherland. He doesn’t have a love interest because his love is Russia, he can’t show weakness because Russia has no weaknesses, he can’t fart because that would be like Russia itself farting, etc…

Sergei Prokofiev’s score is acclaimed but I didn’t enjoy it: its shifts from movement to movement (with wildly different moods) sound weird and inorganic next to modern film scores. It’s probably great. I just can’t find a way into it. The subtitled dialog contains deathless Yoda-esque lines such as “They are strong! Hard will it be to fight them!” that hopefully flow better in the original Russian.

Eisenstein (as noted by Roger Ebert) sometimes made films that ascended directly to “great” without actually being good. Alexander Nevsky feels like that sort of movie: it has a spot on the film school curriculum but maybe not in the hearts of many students. It’s a 50 foot colossus with a clown shoes and a big red nose. Huge, important, towering above the landscape…but at the same time, it’s hard to take seriously.

In short, it’s a film of its time. In nearly every scene, shot, and frame, there’s something that jolts me out of the picture. The film at its best is a 1930s version of James Cameron’s Titanic, lavish and expensive, carrying the heft of history, with some innovative and somewhat impressive filmmaking techniques all built around a massive effects-driven set piece. At its worst, it’s patently absurd and laughable.

That’s one way of looking at Alexander Nevsky. The other is as a source of patriotic hope.

The darkness in the West hangs over all of this. You have to remember the circumstances of its production, who would have wanted to see it, and why. Many of Alexander Nevsky’s apparent flaws disappear when you watch it the way you’d listen to a national anthem as a patriot, or attend a church service as a believer.

The broad characterization and black-and-white morality are like anchors, points of stability in an unstable world. The Teutonic Knights are vile (there’s a horrible scene involving infants being thrown into a fire), but so were the real life Nazis. The film runs highlighter over Russian pride and German evil, relating everything back to the USSR’s contemporary circumstances. The historical garb is thinner than rice paper. I don’t think it was meant to be judged as a movie.

Even the film’s camp moments are interesting. At the start we see a Mongol chieftain offering Nevsky a command position in the Golden Horde (which is declined). He’s a silly fat man with a top-knot that looks like Mickey Mouse’s ears.

I am no expert, but I can’t find a photo of a traditional Mongolian (or Chinese) hairstyle that looks like that. It seems unique to the film. I half suspect we’re supposed to think of Mickey Mouse’s ears – the black cap contrasting with his pale skin completes the image. Mickey Mouse (like Alexander Nevski) is inseparable from one particular country: the United States.

Does the Mongol Mouse represent capitalist America in the film? Just as Nevsky represents Russia? That would explain the ominous dialog where Nevski says that although the Mongols are a threat, the Germans are worse and must be fought first. “The Mongols can wait, methinks. We face more dangerous foes.” The difference, Nevsky goes on to explain, is that Mongols are greedy and can be placated with gifts (like capitalists), while the Germans are evil, destroying all that isn’t them (fascists). This anti-fascist angle, it must be said, now looks odd in light of how the Mongols are depicted as grubby savages, while Cherkasov is a tall, blond Aryan superman.

The rest of the film features more blatant pro-Soviet propaganda. Nevsky butts heads with with wealthy boyars (representing kulaks) and priests (representing…) who don’t understand the danger, want to appease the enemy, etc. Fortunately, Nevsky has the people on his side.

This isn’t even pseudo-history, it’s fan-fiction, like a teenage girl making Harry and Draco kiss. The real Alexander Nevsky was a rich aristocrat who took monastic vows. He wasn’t any kind of rabble-rousing working class hero (let alone an anti-capitalist or anti-clericalist). This is Russia’s 1930s political milieu projected seven hundred years into the past. But this is like noticing that Americans depict Jesus as white: it misses the point. Alexander Nevsky isn’t supposed to depict history except in a superficial way. It’s doing something more elemental, issuing marching orders to a nation.

What about the battle scene?

The final third of the movie is eaten up by an extremely long battle involving elaborate staging and hundreds of extras. The rest of the movie seems draped across this set-piece like a threadbare set of clothes (again, Titanic). When the horns blare and the massed columns of infantry advance onto the ice, you forget about everything that happened before. It’s its own self-contained universe.

The scene is groundbreaking – literally groundbreaking, it ends with an army falling through Lake Peipus – and ranks among the most thrilling moments yet seen in a movie. How did it take just forty years to go from Fred Ott’s Sneeze to this? Even today, the battle looks fairly good. Almost any time you see a motion picture featuring a cavalry charge – be it Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, or Sergey Bondarchuk’s Waterloo – it’s trying to look like Alexander Nevsky, consciously or otherwise.

Yes, you can sort of tell that the actors are being filmed under a bright sun on a hot day, but in black and white it’s not obvious. Films have something called “day for night” (a “night scene” that’s clearly not at night). Alexander Nevski went one further: hot for cold. Sand is used in place of snow. Huge sheets of broken glass are used in place of ice. The incredible thing is that it works.

It must have taken a staggering amount of money to film the battle. The costumes, props, and so forth look perfect, and there are hundreds of them. Within a few years, Russians would be facing the Germans with empty rifles, tanks without radios, etc. There’s a grim irony to the fact that (based on the opening weeks of Operation Barbarossa) the USSR was better at fighting a fake war than a real one.

It has some dated elements. Eisenstein wasn’t able to capture the violence and kinematics of an actual battle. Blows are half-hearted. People fall over dead for no reason. Horses are perfectly calm where they should be white eyed, terrified, and spraying foam.

This moment made me laugh. It was like a Keystone Kops gag.

The sheer length of the battle wore me down. Just shot after endless shot of men swinging swords at enemies conspicuously out of frame. I’ll admit that after twenty minutes of this, I wasn’t overjoyed by the prospect of twenty more.

However, the battle ends on an striking visual: the beleaguered Germans collapse the ice with their weight and drown. This is apparently fiction – no contemporary accounts describe such an event – but it’s good, effective filmmaking, breaking the tedium of the battle and providing effective closure to the ice scene. It’s Chekov’s gun in the end. Put a gun on the set, and it has to get used. Put an army on a a frozen lake, and they have to fall through.

Many nations have legends of sleeping champions (Portugal’s King Sebastian, Britain’s King Arthur, Germany’s Frederick Barbarossa) who will return to fight for their homeland in its hour of need. But the atheistic USSR didn’t believe in such fairytales. They forced Nevsky back to life, through the magic of cinema. They probably thought they had to.

It’s a little hard to recommend the entire movie, although the battle is worth watching. Alexander Nevsky does not escape the time its in. You have to take it for what it is, a propaganda tool for a desperate nation facing desperate times. Seen with this in mind, it has a chilling power. Thunderclouds seem to hang above it. Walls of tanks clank in the background. Ahead lay a nightmare: a war so awful that historians disagree not just on how many Russians died, but how many million. The battle is inseparable from the mechanical savagery of Stalingrad and Kursk. The burning children reminds of the Holocaust.

Few films gain so much from their context, and few films have a context this awful. Alexander Nevsky is like a battle standard overlooking a battlefield. It’s just a crude image of a lion, fluttering in the wind. But underneath that lion are rivers of gore, shattered bones, smashed helmets and vambraces, cries of the wounded, and feasting crows.