A “mockbuster” is a low-budget ripoff of a famous movie designed to trick you (or more likely your grandmother) into buying it. Major Hollywood films can have print and advertising budgets in the range of hundreds of millions of dollars, and just like harmless moths copy the markings of venomous wasps, a well-designed fraud can exploit another movie’s publicity blitz without spending a cent in advertising itself. A rising tide lifts all boats, but it also lifts turds.

Mockbusters are frequently masterpieces of surrealism. Their only desire is to be safe and generic, but they always feel uncomfortable, creepy, freakish, and strange. You might say they follow the rules so hard they break them.

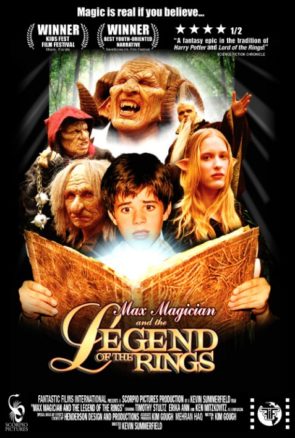

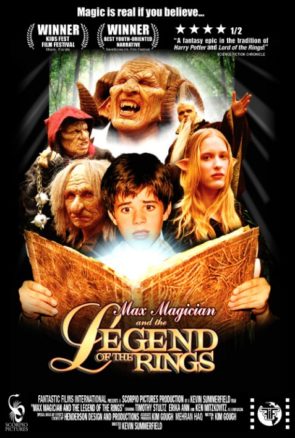

2002’s Max Magician and the Legend of the Rings is an archetypal mockbuster. It wears its can’t-fail concept on its sleeve (or cover): Lord of the Rings was making money, Harry Potter was making money, so if you combined those things into one movie, then hell, you’d make money squared. Money times money. Hopefully this plan worked, because the director clearly had crack debt times crack debt.

What he didn’t have was a budget, actors, set designers, producers, or writers. Nobody involved in the movie seems to know what they’re doing, and some actually appear to be held on set at gunpoint. The result is an experience that has to be seen to be believed: a disastrous collage of fantasy cliches whose shamelessness is matched only by their incompetence. You feel genuine embarrassment for everyone in the zoning district.

Story? A young amateur magician called Max Majeck (you just heard the movie’s funniest joke, by the way) finds a doorway to a fantasy world under attack by a guy in a Ren Faire costume. Max saves the day by reading incantations out of a magic book, unleashing awesome spells such as “slowly levitate a few sticks of wood” and “cause several mice to appear on the villain’s shirt”. Watch out, Stephen Strange.

Everything about the movie is misjudged, including the decision to make it at all. The “fantasy realm” is clearly the woods outside someone’s house. The movie introduces an old, wise mentor character, forgets about him, introduces a second old, wise mentor, and then forgets about him. There’s a character called “Mr Tim” who refers to his wife as “Mrs Tim”, probably because it was too much work to come up with a woman’s name.

Like any truly bad movie, it’s actually hard to critique: it’s a firehose of awfulness overwhelming any cogent attempt to analyse it. An example of the rollercoaster ride the film takes you on: there are elves. They have pig ears. The pig ears don’t match their skin tone. The queen of the elves is played by the same actress who plays Max’s mom. She speaks with the same Midwestern accent in both roles. I literally can’t focus on any one thing because there’s always something worse distracting me.

But the audio stands out as exceptionally horrible. The music is completely inappropriate, sounds like it came from a free stock library, and was queued into the film by a deaf person. Countless lines of dialog are dubbed, suggesting that their original audio was spoiled somehow. They must have rewritten the dialog too, because the lips generally don’t match the voices.

I have to correct some misunderstandings the internet has about Max Magician. The first is the claim (featured on IMDB) that “There are no rings.” No, there are rings in this movie. Mr Tim’s book references magic rings. Dagda steals a green ring from Queen Belphobe.

The second misunderstanding is that it’s just a ripoff of Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter. That undersells the film’s ambition: it also rips off The Chronicles of Narnia (the talking mouse character + the children travelling between world plot point), The Neverending Story (the enchanted book), and Jim Henson’s Labyrinth (the goblins-bickering-in-the-closet scene at the end.)

It’s fairly good “make fun of bad movies” fodder. I suggest going into Max Magician armed with a few facts about it’s production, such as the fact that the weapons are literally pool noodles, or that the talking mouse Crimbil is portrayed by two different mice after the first got eaten by a snake. (You can notice this on-screen because the two mice don’t quite match in color: OG Crimbil is slightly gray, while Emergency Backup Crimbil is slightly brown. Can you identify which scene contains which Crimbil? This could be a drinking game. )

Mockbusters are designed to be disposable. Strangely, this one picked up a second life after pop culture commentary Youtube channel Red Letter Media tried (and failed) to review it. Their video was corrupt and displayed 86 minutes of static. I think my video’s corrupt, too. It displays 86 minutes of shitty movie.

(Ironically, “mockbuster” is itself a linguistic mockbuster, riding on the fame of two prior words – mockery, and blockbuster – to achieve its affect.)

This is a book of nightmares. It can be read online, but should it? You might regret it. It’s up there with “Loving Your Beast” (a zoophile’s guide on how to have sex with your dog) as one of the most excruciating things on the internet.

Who do you love more than anyone else in the world? Think of that person. Now picture being chained to their bloated corpse- forever. What was once my beloved body is now a corpse. I can only describe the feeling it gives me as supernatural revulsion. It’s unthinkable. Flabby, misshapen, atrophied, etiolated. When my legs kick and jerk me around, they seem to me like something indescribably loathsome. Not warm and mammalian or even reptilian. It’s like a crab or a spider. Like the twitching and jerking leg pulled off of a spider. A thing with no soul. Cold and hideous, harrowing, ghoulish. A grotesque, obscene, and hideous thing. It horrifies me and tears at my sanity. Everything inside of me screams to get away from it. How would you feel chained to your beloved’s ghastly, distended corpse? Sometimes when I am around others I feel as if I am struggling not to flinch with tarantulas crawling on my neck in my efforts to hide from everyone the torture I’m enduring.

It began (and ended) with a thread on motorbike forum Adventure Rider. A user with the ominous handle of OZYMANDIAS announced his intent to ride from Seattle to Argentina on a Kawasaki KLR650, his last big hurrah before law school.

He crashed just outside Acapulco, and woke up in a Mexican hospital, unable to move his legs. OZYMANDIAS (real name: Clayton Schwartz) had rolled the dice in the cripple lottery and won T4 paraplegia, meaning his spine was broken below the fourth thoracic vertebrae. Put a finger on the back of your neck, and then walk it down about four inches. Then imagine not using anything below that point – not even the smallest muscle – for the rest of your life.

“I am two arms and a head, attached to two-thirds of a corpse.”

Two Arms and a Head is not a biography but a tortured shriek. It transcends merely uncomfortable and becomes the equivalent of having the contents of a clogged drain oozing down your optical nerves. It’s repulsive and existentially horrifying, like a nonfiction Metamorphosis where Gregor Samsa loses two legs instead of gaining four.

It is not an “inspirational” book…except insofar as it inspires one to never get on a motorcycle. Then it’s the War and Peace of inspirational books.

It’s a wildly successful piece of writing, however, because it accomplishes one of the main goals of the craft: taking an alien experience and making it seem familiar with words. There are things about disability that you’d never think about unless you were there, and Clayton communicates these in unsparing detail.

Losing your body from the armpits down? As bad as that sounds, the reality is worse: Clayton hadn’t lost his body, it’s still there, he just can’t use it. He’s attached to 150 pounds of ballast, a parasitic tumor that makes up 70% of his mass. He repeatedly fantasizes about sawing his useless lower half away. He envies bilateral amputees.

Clayton piles on stomach-turning detail as to how he goes to the bathroom (or shits himself), how he gets into a car (with difficulty), how he deals with with neuropathic pain (he waits for it to stop), etc. He’s a prisoner in his own body. Every activity he used to take for granted is now as mechanically complex as the erection of Stonehenge. Every activity he used to enjoy is now impossible except as a parody of its former self. Going to the beach? That now means sitting on the shore and watching others swim. Building a house? That now means giving advice and passing nails and screws while someone else does the work. Having sex? Denotationally possible, but connotationally not.

The world is designed for the abled. More than that, nature designed us to be abled. He makes a striking analogy: imagine Manhattan was cut in half with a huge saw, and the lower half thrown away. Obviously everyone in lower Manhattan is dead, but upper Manhattan would suffer greatly, too: the fallout from broken power lines, roads to nowhere, destroyed sewage and drainage networks, etc would be colossal. Half a body doesn’t equal half a body, it equals something less, because that half was designed to work as part of a whole.

Most authors from the “disability lit” genre (Nick Vujicic, Sean Stephenson, etc) produce cheerful “I’m disabled and taking life by the balls!” motivational fluff. They’re upbeat, optimistic, accepting of the hand they were dealt, taking each day as it comes, and brimming with peppy slogans. The only disability is a closed mind!

In light of that, it’s genuinely shocking to read a disabled person liken their body to “a living, shitting, pissing, jerking, twitching corpse”. The book’s precis is that disability is a fate worse than death, and that anyone trying to say that this kind of life is worth living is delusionally misguided. He doesn’t want to motivate, just educate. He spends a lot of time kicking disability rights advocates (metaphorically, I mean), who he sees as trying to force a lifestyle – a deathstyle – upon people in his condition, when the most kind thing is euthenasia.

Often there is nothing more unpopular than the truth. I will not make many friends with this book, but that is my lot in exposing many things people would prefer not to see or know about.

Another difference between this and other disability lit books is that Clayton doesn’t really try to be likeable.

I’m sorry to say that, but it’s true. Sometimes he’s insufferably pretentious. The book opens with a literal preamble that name-drops Bertrand Russell, Soren Kierkegaard, and Friedrich Nietzsche. Then we get an angsty rant about religion that sounds like it’s from an atheist teenager’s Typepad in 2007. “The fawning, sycophantic, unquestioning, swooning, pitiable way so many worship God is enough to make me puke.” A fair amount of the book comes off as one-up-manship over other, less disabled people. “Oh, you think you’re disabled? You have no idea!”

Yes, Clayton was more disabled than some. But less disabled than others. He had some reason to be thankful. He only broke his T4 vertebra. A little higher, and he would have lost his arms as well, then the book would simply be called “Head”, and it would either not exist or be about ten times shorter due to the difficulty of composing.

And quadriplegia would have made it far more difficult for him to enact the final part of the plan. I suppose I should spoil it. Clayton’s case is fairly famous, after all.

This is not a book, but a suicide note. There’s a Wile E Coyote moment when you realise intends to kill himself, where it doesn’t register as real, and then he plunges you off a cliff.

There are things in the final part of the book that I never thought I’d read. He describes the knife entering his stomach in as much detail as he can, which is a lot. Clayton was wrong in the end: his disability did give him something denied to a normal person: he was able to write lucidly about stabbing himself while doing it, without overwhelming or short-circuiting from pain. The book’s final pages are extremely disconcerting: he wavers between nihilism and cheerfulness, sanity and loopiness, and the book simultaneously ends and crashes to a stop.

It’s very rare to see a man’s mental stage fluctuate so nakedly on the page. It reminds me of Louis Wain, who was an artist who drew cats. In his early years, they were naturalistic portraits, and he made a good amount of money selling them as postcards But as schizophrenia took hold of his brain, the cats became twisted and terrifying: resembling owls, monsters, demons. In his final years, they were little more than abstract explosions of light.

…Or so the common story of Louis Wain goes (some art historians now dispute it). But it’s what I thought of as I watched Clayton die: his vocabulary shrinks (or bleeds out), he makes increasingly frequent grammar and punctuation errors, and he becomes preoccupied with the bottom parts of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. He feels hot. He’s sweating. He feels dizzy. And then…

It’s a grim story, but a true one. And most importantly, it’s one that’s going to happen again. Other people are caught in Clayton’s situation. What can and should be done about them? What are the limits of life we should tell people to accept?

If nothing else, it’s worth remembering Clayton, the man who tried to find a silver lining on a cloud that covered the entire sky.

“I’m going to go now, done writing. Goodbye everyone.”

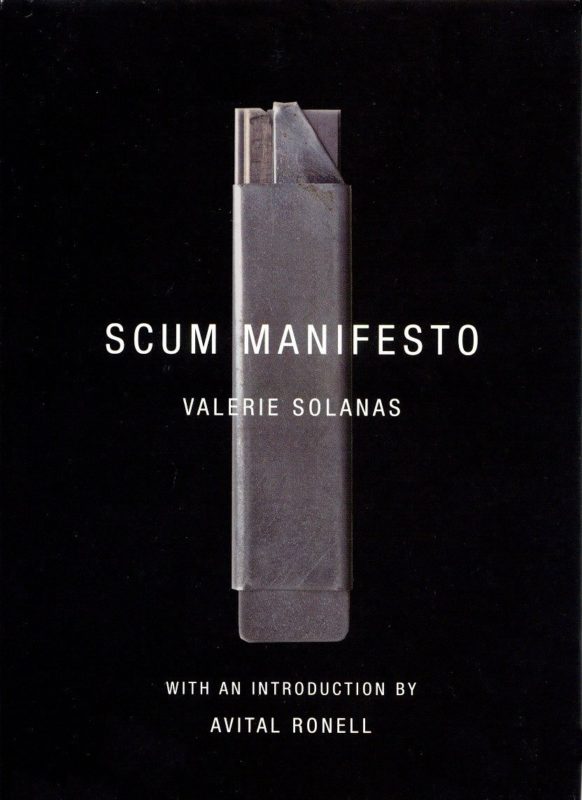

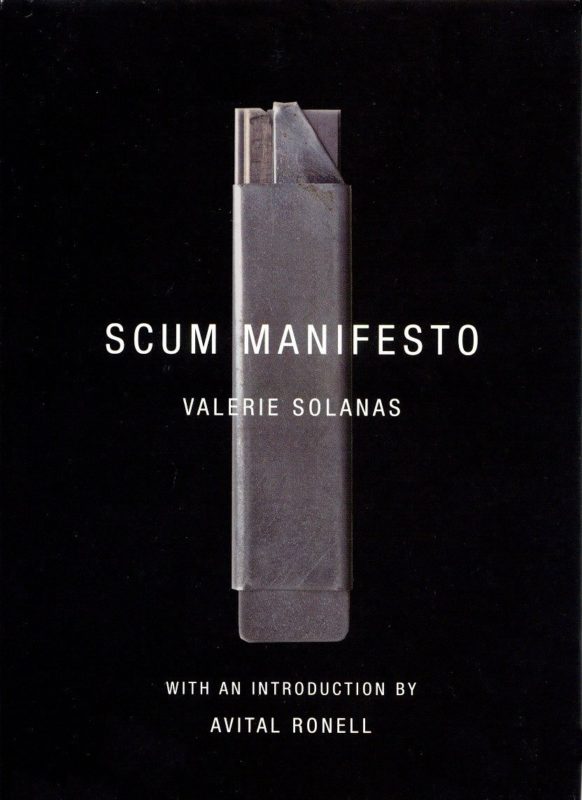

At the risk of sounding like a dril tweet, you gotta hand it to Valerie Solanas. She saw a problem and did everything in her power to fix it. Of all the feminist theorists scribbling about society’s war on women, Solanas was one of the few who truly meant it. She’s in a class with Elliot Rodger, Fred Phelps, and Pol Pot: true believers who make you feel as small as an insect because they bled for their beliefs as you’d never do for yours. Reading SCUM Manifesto is like “reading” the shattering wall of light from a plutonium bomb explosion at ground zero: it’s hard not be blinded by the intensity of Solanas’s faith.

“To call a man an animal is to flatter him; he’s a machine, a walking dildo.”

The disease: men. The cure: no men. In SCUM Manifesto (which is not titled The SCUM Manifesto, the Scum Manifesto, or any of the internet’s misspellings) Valerie Solanas outlines the failings of male-governed society and proposes radical action: Eve needs to take her stolen rib and plunge it back into Adam’s chest, sharp end first.

You may have heard that SCUM stands for “Society for Cutting Up Men”, but Solanas doesn’t want to cut up men, precisely. She feels that men can be rationally convinced of their uselessness, at which point they’ll “go off to the nearest friendly suicide center where they will be quietly, quickly, and painlessly gassed to death.”

Is the book meant as satire? It could be read that way. The rest of Solanas’s life is a compelling argument that it isn’t. Much of the book is clearly an inversion of Freudian psychoanalysis (it proposes that men suffer from “pussy envy”, and so on). But that doesn’t necessarily mean that Solanas is insincere: serious ideas are often formulated in the shadow of their opposites (Hegelian antithesis, etc.), and it’s likely that SCUM Manifesto contains an extreme or distorted version of Solanas’s true feelings.

As an academic and one-time actress, she would have known of Antonin Artaud’s “Theater of Cruelty” method: exaggeration; cranking up the volume; overloading the senses; shoving actors and audience alike past their comfort zone. SCUM Manifesto might be a Book of Cruelty, intended to shift the Overton window so that milder versions of SCUM would be politically viable. Or she may have been crazy. Or crazy like a fox. To be a chauvinist pig, she wasn’t a fox in any other sense.

What’s often overlooked about this book is Solanas’s utopian visions of the future. SCUM Manifesto is nearly a misclassified science fiction novel: Solanas foresees a world containing ATMs, electronic ballots, automation, UBI, luxury communism, the end of death itself, and…Tiktok?

“[FOOTNOTE: It will be electronically possible for [a male in the future] to tune into any specific female he wants to and follow in detail her every movement. The females will kindly, obligingly consent to this, as it won’t hurt them in the slightest and it is a marvelously kind and humane way to treat their unfortunate, handicapped fellow beings.]”

That’s no way to talk about Belle Delphine’s subs. Solanas stresses that we (meaning her 1970s readers) would be enjoying all these things already if it wasn’t for men ruining everything. It reminds me of those dubious graphs on atheist message boards, where humanity’s rising progress gets bodyslammed from the top rope by the CHRISTIAN DARK AGES. We’d be colonizing the galaxy by now, if Constantine I hadn’t gotten baptised. Although we are, when you think about it. A one-planet-sized portion of the galaxy.

SCUM Manifesto can also be read as comedy. I’m not joking: Solanas is hilarious. Her prose is a mixture of histrionic sincerity, phrasing as odd as an Achewood comic, and 1960s “groovy, man” lingo that’s impossible to imitate and impossible not to laugh at. Why didn’t anyone tell me it was this funny?

“SCUM is too impatient to wait for the de-brainwashing of millions of assholes. Why should the swinging females continue to plod dismally along with the dull male ones? Why should the fates of the groovy and the creepy be intertwined?”

“The sick, irrational men, those who attempt to defend themselves against their disgustingness, when they see SCUM barrelling down on them, will cling in terror to Big Mama with her Big Bouncy Boobies, but Boobies won’t protect them against SCUM; Big Mama will be clinging to Big Daddy, who will be in the corner shitting in his forceful, dynamic pants.”

Surely Solanas wasn’t totally serious. Nobody could write “forceful, dynamic pants” and actually mean it.

Or could they? This is the most fascinating thing about the SCUM Manifesto: it’s as forceful as an anvil to the face…and nobody’s sure what it means. To anti-feminists, it’s a stick to beat feminists with. To feminists, it’s variously a reactionary horror from the 60s; a brilliant satire like A Modest Proposal; or a work to be approached with sympathy and compassion, containing the howl of a woman pushed to the edge and then far, far, over it.

It’s a radical document. It’s a foundational text of Second-Wave Feminism. Some want to burn it, others want to teach it. Few works mean so many things to so many people.

Solanas’s legacy is one of failure and unfulfilled dreams. SCUM Manifesto will soon be fifty years old: its promised utopia has yet to arrive: men still exist, the fates of the groovy and the creepy remain intertwined, etc. Solanas’s faith could move mountains, but the mountains all moved back. SCUM Manifesto might never have achieved notoriety at all if had hadn’t come wrapped around a metaphoric and literal bullet. It’s a final irony that her name will go down in history so indelibly linked to that of a male that she might as well have married him.