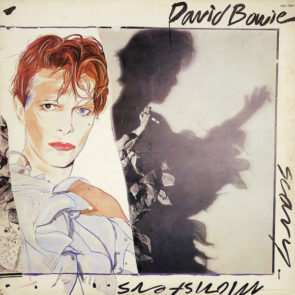

Scary Monsters and Super Creeps is Bowie’s Except Album, meaning it often appears along with the word “except”. “Bowie sucked in the 80s, except for Scary Monsters“. “Bowie was never good when he tried for mainstream success, except for Scary Monsters“, and so forth.

It’s also often spoken about in the same sentence as “scary” and “monsters”. Though that’s less surprising, since that’s the name of the album. It would be strange to talk about the album without mentioning its name, although it would be a fun challenge to do so (and also without identifying it another way, such as “the Bowie album from 1980”). Kafka led a man to the executioner’s block without ever mentioning his crime. Could you arrange words in such a fashion that a reader understands the music, without ever actually being made aware that the album exists?

Scary Monsters is about decay. Not decomposition, not morbidity, just…things falling apart, in a general sense. It’s an album about the crack in your ceiling, and the verdigris embroidering your bathroom floor. All the things you’ve been meaning to fix, even as they advance to an event horizon where it’s not worth the bother.

Bowie assembled some of the finest guitarists to ever set plectrum to string, and made them play sloppily. Vocals are deliberately flat, or mangled oddly in the mixing room (the heavy tremolo rattling the chorus of the title track both disturbs and fascinates). The lyrics discuss fashion and aging, yet they all seem to be about the House of Usher. The building is tumbling down, we’re caught inside it, and we can never leave. Bowie sings about disillusionment and weariness, his voice cracked and broken. None of his albums – not even Aladdin Sane or Outside – evoke this kind of genteel neglect.

“It’s No Game, Pt 1” opens the album in thuggish fashion. Someone took the song, punched it around, and gave it a black eye. Fripp’s guitar part swirls like stagnant water, the drums kick out at you, and it’s interrupted by outbursts of Japanese female vocals, as though someone spliced in the hourly Harajuku traffic report. Although this is the closest solo Bowie ever went to punk rock, it’s cerebral and calculated beneath the blood: more like Public Image Ltd than the Sex Pistols.

Other tracks document various vanishing trends in Bowie’s music. One of the last great Bowie epics (“Teenage Wildlife”) can be found here, as can shorter but equally memorable cuts like “Up the Hill Backwards”. Be sure to get the version with the bonus track, “Crystal Japan”, which was written to score a TV ad for a sake company (of all things) but dredges up strong memories from the Brian Eno years.

“It’s No Game, Pt 2” is a slower and less enthusiastic reprise of the first part. There’s an old Hollywood joke: at eight in the morning you’re shooting Citizen Kane, at eight in the evening you’ll settle for Plan 9 From Outer Space. This song captures that kind of exhaustion and weariness, freezing it under glass.

This album has a reputation as a Bowie threw away most of his artistic pretensions and went fishing for hits. Happily, he caught one (“Ashes to Ashes”). Even more happily, the reputation is wrong: he didn’t throw his artistry very far after all. There’s louche experimental moments all over Scary Monsters. This is the rarest thing: an artistically successful commodity. It’s also one of his most consistent and listenable works. Clearly, the future was bright. He would not put a foot wrong in the 1980s.

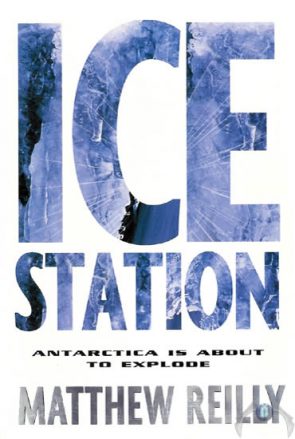

It’s an odd idea to write books for people who never read them, but it’s worked for Mr Reilly so far. Ice Station is a brutally fast-moving action thriller novel that seeks to be a movie on paper – probably one directed by Michael Bay.

Like all of Reilly’s work, it barely exists as literature: it’s a screenplay with cover art and an ISBN number. The typical paragraph is one line long. The typical adverb is “suddenly”. Descriptions are sparse and visual. There are comic book sound effects whenever someone has their head blown off, which is often.

The book stars US marine Shane Schofield, whose unit has been dispatched to a remote Antarctic research station (are there any Antarctic research stations that aren’t remote?). A metal object has been discovered in a 100 million year old layer of ice: it could be an alien spacecraft. Since nobody “owns” Antarctica, a number of foreign nations are attempting a snatch and grab mission to seize the discovery.

We get about forty pages of backstory (meaning, Reilly setting up dominoes so they fall in the most destructive way possible), then the action begins and never stops. Schofield ends up fighting French soldiers, British soldiers, his own unit, the environment, killer whales, frostbite, etc,

You could probably build an Antarctic research station from the combined metal of all the ejected bullet casings in this novel. The story’s so addictive and streamlined that it’s hard not to read in one go, in fact, experts say the average person reads at least seven Reilly novels per year in their sleep without realising it.

The obvious movie cliches appear: a nerdy scientist who plays Captain Exposition, a cute little girl with a pet, a traitor on the team, a rushed romantic subplot, etc. Reilly doesn’t know how to write anything except action, but it’s amazing action. A high-speed hovercraft chase and a tense battle in a killer whale infested pool particularly stick in the memory. He also knows the media his audience might be familiar with, and includes nods to Die Hard, Tom Clancy, Michael Crichton, and the X Files in all the right places.

Reilly’s plotting is often cited as incompetent, but it’s actually entirely competent – it’s just geared to something other than making perfect sense. Basically, whenever “cool” clashes against “logically plausible” (or “physicially possible”) cool wins. This is the Rosetta Stone to making sense of Ice Station.

For example: Schofield breaks a rib in this story. In the real world he would have great difficulty accomplishing some of his later feats in the story (such as swimming hundreds of meters), but that’s irrelevant. Reilly is the God of Cool, and sometimes he allows the mortals in his universe to break the laws of physics. Schofield needs to keep doing cool stuff, so he does it with a broken rib.

It would be funny to read a “self aware” hero who knows he’s in a Reilly novel (think Scalzi’s Redshirts). He’d try to stay alive by doing the most outlandish and ridiculous things possible. He’d dash to the nearest pet store and buy a cute dog. In fact, he’d wear body armor made of cute dogs stapled together: nobody would dare shoot a bullet at him. He’d also hire a plastic surgeon to make him look like an A-list Hollywood actor (Schofield’s physical description is a dead-ringer for Tom Cruise).

A realistic depiction of the story’s events would also make an interesting novel. Legally, Antarctica is not an ownerless waste, it’s a condominium – jointly owned by twelve nations. If an alien spacecraft was discovered, nobody would send special forces to capture it. Such a “capture” would be worthless – a huge metal object can’t realistically be transported or removed by twelve guys with guns, and it would stay in Antarctica, no matter who wins the shootout.

In Ice Station a group of bad guys hatch a plan to free the spacecraft (if that’s what it is) by detonating thermonuclear charges, creating a new iceberg with the spacecraft inside it, and steering the iceberg north to their sovereign territory. But then it would be pretty obvious what’s going on, and since the Antarctic treaty forbids the detonation or testing of weapons, you might as well declare war with half the world.

I read Ice Station at fourteen (the correct age), and it remains my favorite of Reilly’s work. It’s efficient, the prose is as tight as the wires in a Hong Kong action movie, and it avoids the goofy GI Joe cartoon feel that spoils some of his later work. It’s obviously nobody’s idea of a literary treat, but you don’t need spaceships to fly, and Ice Station proves it.

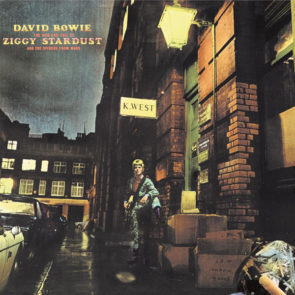

The eye sees by transmitting light from the retina to the optic nerve, and then to the brain. The problem is, the optic nerve runs in front of the retina itself, blocking a sliver of light. In order to see, you must have a blind spot.

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars is my blind spot. It’s the only Bowie album I like and yet don’t “get”. Musically, it has some of his best work. Conceptually, all the stuff about fake rockstars and androgyny and the world ending in five years seems bizarre and unnecessary, like you’ve invited a friend to stay the night and he’s brought along a U-haul full of childhood toys. It must have struck a nerve (optical or otherwise) at the time: Ziggy Stardust launched his career. But in the 21st century, he’s shadowboxing at targets I cannot see.

Not only did Ziggy not need to be a concept album, maybe it wasn’t meant to be one. It’s rock and roll’s dirty secret that most “concept albums” are retroactively branded as such long after the album is finished (the most famous one, Sgt Pepper, has no concept at all that I can detect). It’s true that many (or perhaps most) of Ziggy Stardust‘s songs don’t tie back into the main story, and the ones that do are jumbled out of order. The most persistent through-line is that Bowie likes writing songs with the word “star” in the title.

The album helped put glam rock on the map, but it’s also a preview screening of Young Americans: lots of soul and jazz moments pop up, sometimes improving the album and sometimes detracting from it. “Five Years” and “Soul Love” are a bit too long and musically subdued to work as album openers, particularly in the second case, where the dominant instruments are hi-hats and congas. “Moonage Daydream” is the first legitimately great song, with a bombastic introduction and a hallucinatory chorus. “Starman” is charming and irresistible, and sounds very much like a song left over from the Hunky Dory sessions.

Unlike the front-loaded Hunky Dory, Ziggy Stardust‘s best moments happen on side B. “Lady Stardust” is an powerful piano ballad, “Hold on to Yourself” an energetic homage to Ed Cochran’s “Somethin’ Else”, and “Ziggy Stardust” sports an instantly memorable main riff, built around a minor 2nd hammer-on with the pinkie finger. Bowie would work with more skilled guitarists than Mick Ronson, but few if any had his taste and discernment. Every note Mick played meant something.

“Suffragette City” is the album’s greatest song, a fierce and pummeling broadside against the Rolling Stones. While “Starman” points to his past, this points to his future: it would have fit anywhere and everywhere on Aladdin Sane. “John, I’m Only Dancing” is a nice curate’s egg if you have the Rykodisc remaster, with a strong chorus and funny queerbaiting lyrics, although I prefer the cut from 1973.

No doubt Bowie-ologists find more in Ziggy Stardust‘s concept than I have, whether it actually exists or not. Take the name “Ziggy”, a strikingly unusual name that would be worth 19 points if it could be played in Scrabble and seems pregnant with meaning. Is it an abbreviation of “syzygy” (a planetary conjunction or apposition, which would reinforce the cosmic theme)? But David eventually admitted that it meant nothing. He just wanted a name that began with Z, and found one in a list of names.

But Bowie was always someone who could turn pewter into gold, and even unremarkable ideas can seem irresistibly clever if sold right, which in the end is the rockstar’s true calling. Ziggy Stardust deserves its place at Bowie’s masked ball, even if that place isn’t quite at the head of the table.