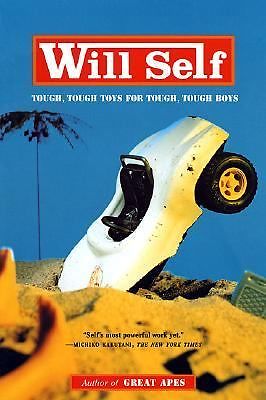

In 2012 I read Will Self for the first time – a free online story called “The Rock of Crack As Big as the Ritz”. This “free” story ended up costing me $10.95AUD, as I had to get the full collection immediately to find out how it ended.

In 2012 I read Will Self for the first time – a free online story called “The Rock of Crack As Big as the Ritz”. This “free” story ended up costing me $10.95AUD, as I had to get the full collection immediately to find out how it ended.

It was a taut, exciting story about a black ex-serviceman who is trying to stay straight and instead spirals into a life of crime like a spider down a plughole. It was impossible and surreal but gritty and naturalistic. It broke all sorts of rules about showing-and-not-telling, but that only helped accelerate the story’s pace. The main character, Danny, is unlikeable, and yet I like him – no contradiction there. “Rock of Crack” is an a pulse-pounding page-turner, a non-stop thrill-ride, an [insert gratuitously hyphenated compound words here], and its sequel in this collection, “The Nonce Prize”, is nearly as good.

The other stories are more diverting than fascinating, although I liked “Flytopia”, which is about a man who can communicate with insects in his house. Very much like a Paul Jennings story for grown-ups, with the surreal, pillowy quality of a dream five minutes before the alarm rings. The others are one-idea jokes – entertaining, but they don’t stay with you. “A Story for Europe” brings back the 80s fad of body-swap stories, but in a realistic and semi-serious way. “Design Faults in the Volvo 760 Turbo” is an amusing take on car fetishism.

Some of the stories don’t work – “Dave Too” is dull and obscurantist, for example. Will Self is a talented writer but I think he makes the common mistake of thinking that uninteresting stories will magically become interesting because he’s the one writing them. Not so. It’s the jokes that get the laughs, not the comedian.

“The Nonce Prize” brings back Danny and friends – sort of. The central conceit of “Rock of Crack” is missing (Self offhandedly writes it out of the story in a few sentences), and the characters’ personalities seem to have changed. But it does give Danny a shot at redemption, as he is framed for a brutal crime by a Yardie drug lord and railroaded to prison.

Away from drugs, and trying to avoid the usual fate of paedophiles behind bars, Danny takes a creative writing class and discovers that he has talent at something other than cutting crack. When he learns of a intraprison writing contest, he decides to enter. People looking for an uplifting Hollywood ending should keep looking, but the ending has a ray of hope for Danny, and is even inspirational after a fashion. A man stuck in mud has often won just by not allowing himself to be pulled down any further.

Toys/Boys should be viewed as either a good but inconsistent collection, or a very good two-part novella with some bonus stories. “Rock of Crack” and “The Nonce Prize” are both excellent (especially the former), but the others don’t measure up. Lightning might strike twice, but striking three times is a bit much to ask where Will Self is concerned.

No Comments »

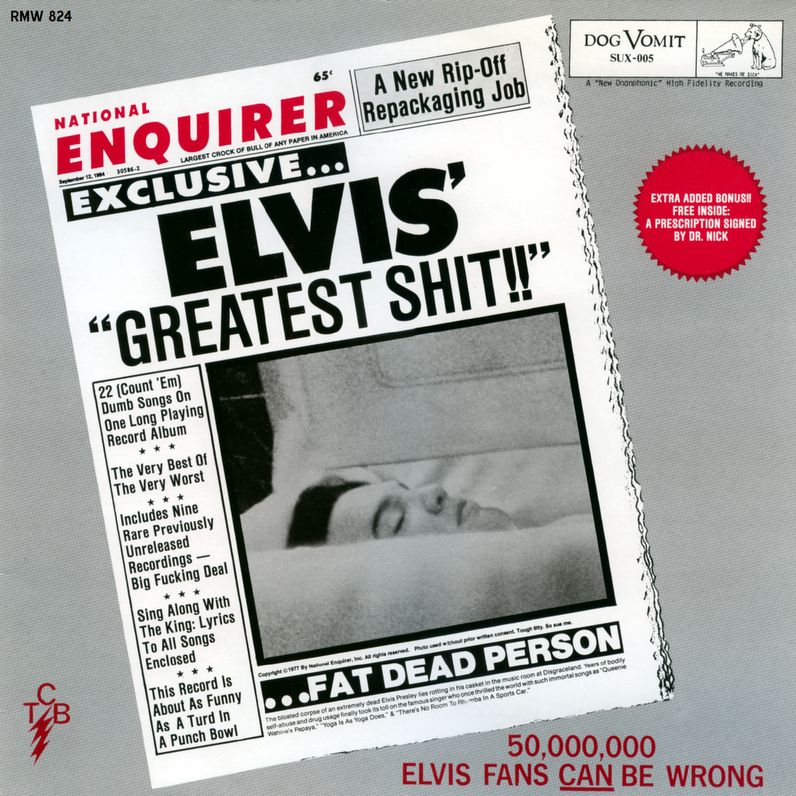

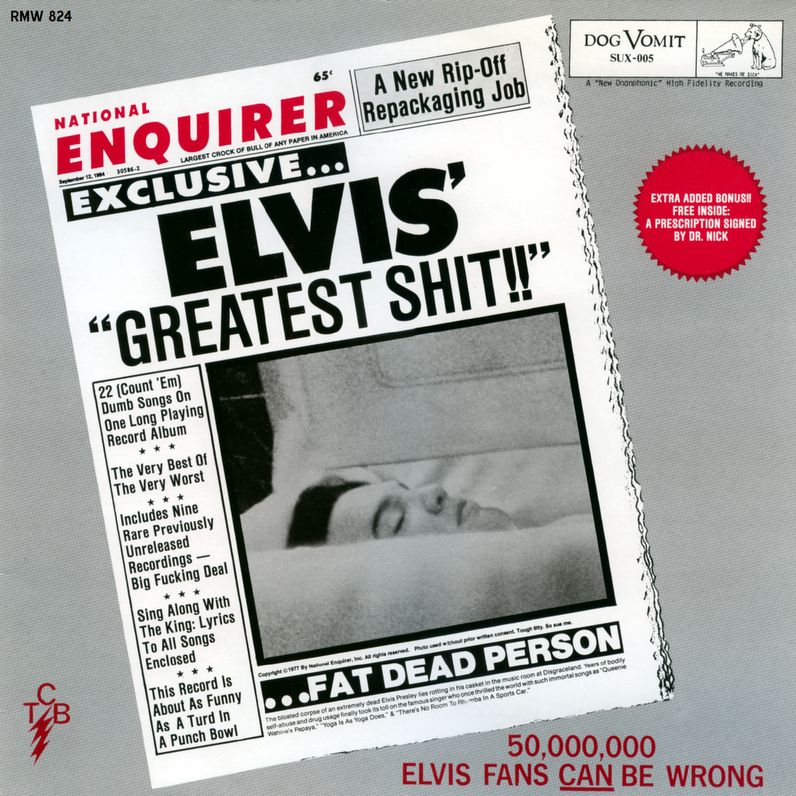

It’s not as notorious as “Having Fun with Elvis on Stage” but it’s probably the most famous Elvis bootleg to actually contain music. Released on the “Dog Vomit Sux” label (a subsidiary of “Dead Obese Guy Enterprises”), Elvis’s Greatest Shit kifes shitty b-sides and soundtrack songs and presents them in a lovingly disrespectful package. The goal, apparently, was to remind people that Elvis was human.

It’s not as notorious as “Having Fun with Elvis on Stage” but it’s probably the most famous Elvis bootleg to actually contain music. Released on the “Dog Vomit Sux” label (a subsidiary of “Dead Obese Guy Enterprises”), Elvis’s Greatest Shit kifes shitty b-sides and soundtrack songs and presents them in a lovingly disrespectful package. The goal, apparently, was to remind people that Elvis was human.

Honestly, it compares favourably to Roy Orbison’s efforts at making disco, or Brian Wilson’s rapping, or the more ghoulish Beatles songs such as “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer.” Greatest Shit isn’t as musically intolerable as you might think or hope. The main reason? It has Elvis singing on it.

As a performer, he’s too good, and he keeps making these bad songs sound better than they have a right to be. “Old McDonald Had A Farm” made me laugh at the start, but then Elvis’s timeless baritone got me under its spell. The songwriting is consistently dreadful, but that doesn’t mean the songs are also consistently dreadful. The end result is often like a skilled poker player winning the river on a bad hand.

Elvis came from the period when albums existed to promote singles. Stab down a turntable needle at random on nearly any late 50s to early 60s LP and you’ll likely hear impaled bad music bleeding and writhing through your speakers. Elvis was no exception – even his some of his supposed classics sound boring and uninspired to me. I don’t believe “Now or Never” have been a hit without the push of the Elvis name behind it.

A lot of these songs come from soundtracks – specifically, films from his flower-necklace-and-hawaiian-guitar days, and obviously they sound odd with no context. And a lot of them are gag songs, with comical lyrics – “(There’s) No Room to Rhumba in a Sports Car” takes a courageous stand against dancing inside moving vehicles, and “US Male” (often considered the album’s classic) is full of funny chauvinism.

The packaging’s a hoot, too. The back cover contains images of nonexistent Elvis LPs “Dead on Stage in Las Vegas, Aug 20th 1977” and a vocal duet with Richard Nixon. The front cover contains the iconic picture of Elvis lying in his coffin – ultimate proof that Elvis was human.

No Comments »

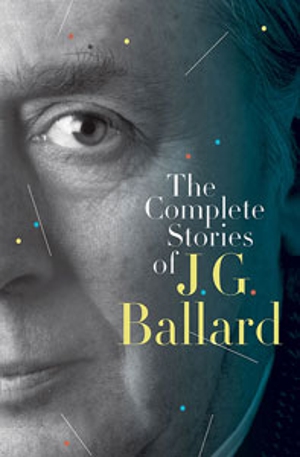

I don’t know if this really is his complete stories. It’s 1200 pages and the print’s really small.

I don’t know if this really is his complete stories. It’s 1200 pages and the print’s really small.

Ballard was either a genius or a near genius, and possessed an incredible imagination. Reading him gets uncomfortable, because my weaker imagination suffers feelings of inadequacy. I feel like a Commodore 64 downloading data from a CRAY supercomputer.

SF has historically come in two branches. The first deals in speculation, the second in reflection. The first deals in “what if” scenarios and whimsies of the imagination, the second deals with apocalypses and dystopias and the real-world consequences of those whimsies. Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke are masters of the first type, Harlan Ellison and John Christopher masters of the second, but JG Ballard did both styles really well. He writes mind-candy that’s also a poison pill – even his unabashed SF efforts are shot through with unease and disquiet, if not outright horror.

The first two stories are pleasant, then we get to “Concentration City” – a stark tale about a man trying to escape a claustrophobic urban jungle that seems to extend to infinity in every direction. Similar themes appear in a later story called “The Enormous Space”, which is about the discovery of a strange space station, about five hundred meters across. Astronauts land on it, and start exploring. The more the station is examined, the bigger it seems to be, until eventually it seems to enclose the entire universe.

And so on. Not all the stories are great, but even the mediocre ones have imagination, inventiveness, and the frisson of discovery. The 98 stories are in roughly chronological order, which breaks up the flow of the original collections but allows the opportunity to watch his style evolve, from his nostalgic golden age SF stories to his surreal, post-modern phase. His best stories contain elements of both periods. Ballard was an ideas man, but also something of a literary bridge-builder.

That’s a good thing, because although Ballard’s imagination was superhuman, as a writer he was merely adequate. Among other things, Ballard’s prose has a lot of disconnected metaphors – odd, confusing similes that are unrelatable to the object in the sentence. Stephen King gave a funny example in On Writing – “He sat stolidly beside the corpse, waiting for the medical examiner as patiently as a man waiting for a ham sandwich” – and Ballard is nearly as bad sometimes. A few paragraphs into “Prima Belladonna” and I was hit with “When I went up I found them grinning happily like two dogs who had just discovered an interesting tree”…what does that mean? Did they need to use the bathroom? In “The Time Tombs” a character says “after five minutes he drains me like a skull.” Out of all the drainable things in the world – sieves, basins, what have you, why a skull? What’s the illuminating connection there? Ballard’s writing is often good, but it often has a careless, smashed-out-at-120-words-a-minute quality, as if the ideas were too hot to stay inside Ballard’s brain and had to be put on the page as soon as possible.

Given the strength of some of these stories, I can’t blame him. But he’s the kind of writer where you have to ignore the trees and look at the forest – his ideas and imaginings are better than his sentences and his paragraphs. But when Ballard is on point, his ideas and imaginings are better than nearly everyone else. This is an amazing collection and should be sought out ahead of any of his novels.

No Comments »

In 2012 I read Will Self for the first time – a free online story called “The Rock of Crack As Big as the Ritz”. This “free” story ended up costing me $10.95AUD, as I had to get the full collection immediately to find out how it ended.

In 2012 I read Will Self for the first time – a free online story called “The Rock of Crack As Big as the Ritz”. This “free” story ended up costing me $10.95AUD, as I had to get the full collection immediately to find out how it ended.