What happened to this band, and what are the chances of it unhappening?

What happened to this band, and what are the chances of it unhappening?

Helloween’s latest album has some good songs. Not too many – you won’t need to graft additional digits on to your hands to count them – but they’re there. Yet it doesn’t matter. The magic is gone. What happened to the good old days, when the songwriting was careless and free? Helloween is now an overcalculated parody of itself.

To recap, Helloween’s Keeper of the Seven Keys 1 and 2 established them as a band of huge promise in the late 80s. Speed metal was already desiccating into something dry and unappealing – Helloween sounded fun, colourful, and catchy. They soon moved away from metal and started aping The Beatles, which went over as well as you’d expect.

The band reshuffled its lineup and had a nice little renaissance in the mid 90s, with Roland Grapow on lead guitar and Uli Kusch on drums. Then that lineup collapsed at its high point (The Dark Ride), and the band decided to call it a day. Or so my crack fantasies go. In reality, here we are with yet another not-so-essential power metal album.

It has better production than the last few albums, but that highlights what a meatless meal this is. Most of the songs are simply not good. And even when they are good, they’re an obvious, safe kind of good. Opening track “Nabataea” is one from the latter category, containing a rote progression of effects-laden intro –> Iron Maiden melodies –> Megadeth thrash riff –> etc. Very predictable. You can almost hear the band ticking things off a list.

That song was written by the guy behind the microphone. If you want to talk about The Beatles, Andi Deris is this band’s Paul McCartney. He’s written some of their most powerful and interesting songs (“Before the War”, “The Shade in the Shadow”, “Time”), but also some of their most commercial and irritating (“As Long as I Fall”, “Mrs God”). On this album, he is an outright liability. He contributes five songs, and three of them are hogwash. Firing Deris would not save this band but it would be huge step in the right direction.

The album’s best moments are penned by Michael Weikath. The scorching mini-epic “Burning Sun” and the catchy and nostalgic “Years” are very good songs, I keep coming back to them even after I’ve forgotten what’s on the rest of this disc. In the Keeper era, Weikath was the band’s weak link. Now he embodies everything that’s still good about this band.

Grosskopf still has his highly active basslines, and Sascha Gerstner makes a fairly good lead guitarist (Roland cannot be substituted for.) I don’t know why I dislike Daniel Löble’s drumming. Maybe it’s the overloud cymbals, maybe it’s his fill-heavy style that tries to make the music all about him. Competent musicianship all around.

But competent musicianship doesn’t mean competent music. Straight out of Hell is boring and crappy. Didn’t they realise that nobody wants to hear “We Will Rock You” by Queen ever again, and that rewriting it into a 2 minute joke song called “Wanna Be God” is gilding a venereal lily? Didn’t they realise that three of these songs (“Far Beyond the Stars”, “Make Fire Catch the Fly”, and “Church Breaks Down”) have the exact same chorus? Didn’t they realise they should have broken up years ago?

No Comments »

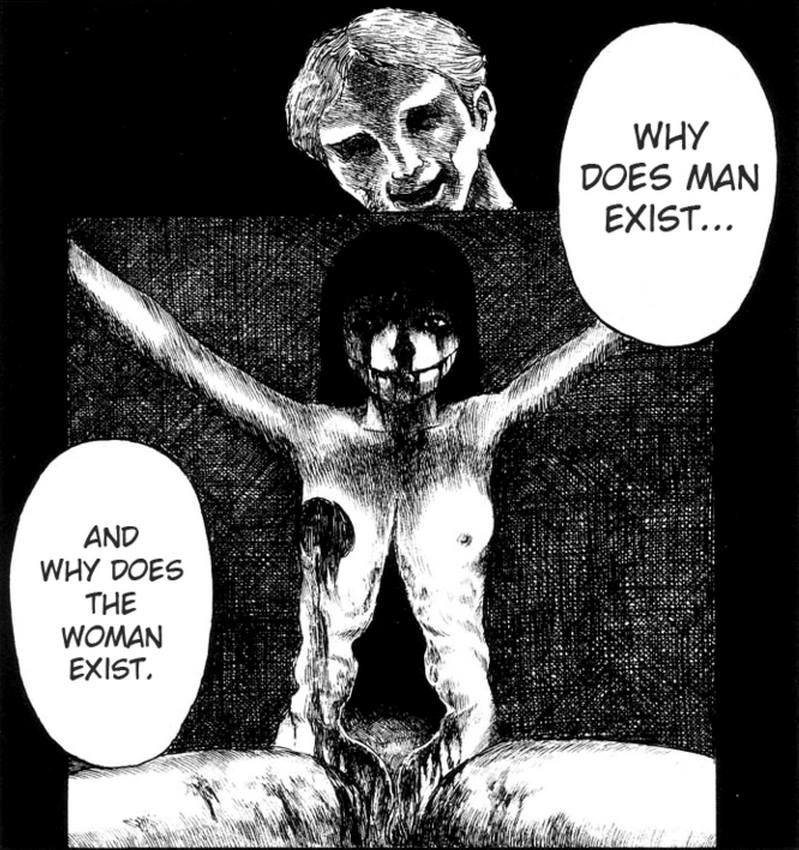

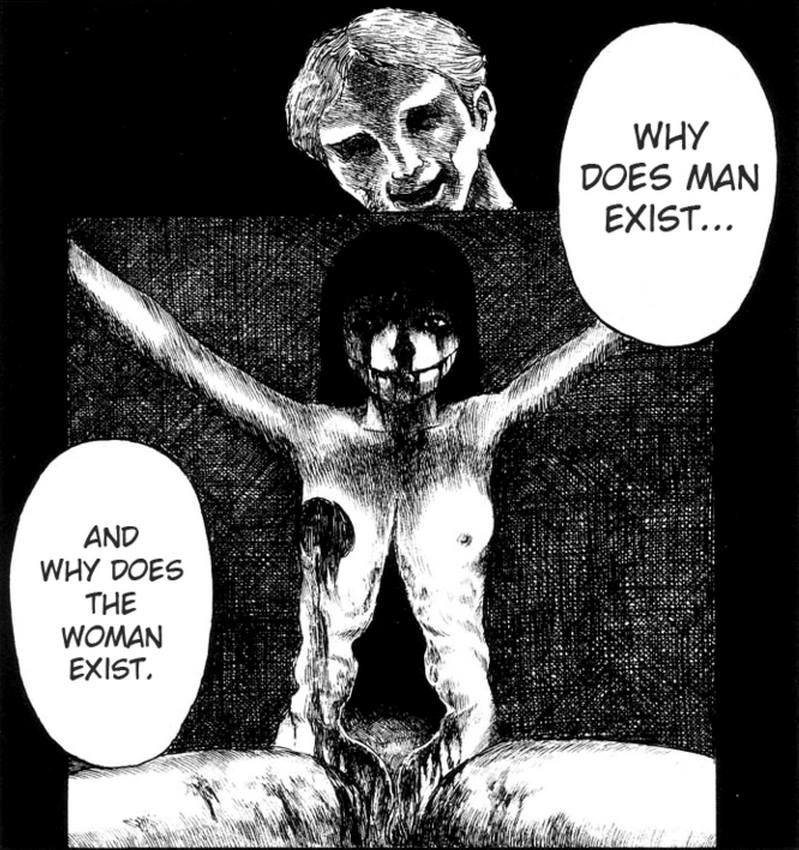

In this movies, a common joke is a schoolboy with a porn magazine hidden behind a textbook. Hell Season is the kind of thing you’d have hidden behind a porn magazine. It is an infamous 10 chapter volume of gore, sex, and unwholesomeness, put together by an all-star lineup of guro artists (Waita Uziga, Shintaro Kago, Machino Henmaru…)

In this movies, a common joke is a schoolboy with a porn magazine hidden behind a textbook. Hell Season is the kind of thing you’d have hidden behind a porn magazine. It is an infamous 10 chapter volume of gore, sex, and unwholesomeness, put together by an all-star lineup of guro artists (Waita Uziga, Shintaro Kago, Machino Henmaru…)

I should warn you that the production values aren’t terribly high. Asuka Shiraishi’s manga doesn’t even look finished – you can see construction lines in his drawings. In some cases the stories are bogged down by poor-quality art, but in some cases they transcend it, as in one notable instance at the end.

Kago’s “When All Is Said And Done” opens the festivities. If you want bleeding rectums, this comic’s got them. Another perennial guro trope – quadruple amputees – makes an appearance, too. All in all, a good story, although it’s not as imaginative as you’d expect from him.

Uziga’s “This Piece of Meat is Talking” comes next. What can I say about Waita Uziga? He’s brutal, and he likes to go for Bambi-like emotional trauma, too. All of his panels contain someone either crying or dying. Unfortunately, his art is a mess…a blizzard of geometric shapes with wonky shading, making it a forensics-like challenge to work out what’s going on. His characters have a very stereotypical “big eyes” anime look to them. I’ve always found it hard to get into guro when I can hear the Sailor Moon theme in my head.

“The Holes” by Machino Henmaru is pleasant for most of its length, and has a mule-kick of a final page that sends it completely over the top. “Rotten Bud” by Mitsuka Hattori has a nostalgic Suehiro Maruo atmosphere that I really enjoyed.

The final few stories are a bit arty and weird. “Mechanical Destructive Killcommand” (try finding a more anime title than that) evokes memories of 80s crap like MD Geist and Genocyber – soldiers fighting a war with a purpose that isn’t clear, with ill-explained weirdness occurring all around them. “Shameless Ranger” is less oblique and a bit more elaborate, but there’s still a jarring sense of having walked into a party halfway through – that we’ve missed out on important events, and that the manga was written to be that way.

Jun Hayami’s “Crowd of Shit-Sacks” (awkward translation, I think) is the true classic from the volume. The art is shit, but the mood Hayami evokes is fascinating, and the atmosphere is extremely bleak. There isn’t that much of a story, it’s more a stream of images describing exempli gratia desolation and abandonment . This one really depressed me when I first read it. Jun Hayami is an amazing talent who got a bit of exposure with Creation Books’ Beauty Labyrinth of Razors – I doubt you can get a copy of that now.

Show this to your mother and she’d cut you out the will, cut you out of the family, and probably cut you in more literal ways. But it’s fun if irredeemable look into the destructive backbrain of one of the world’s more repressed countries.

No Comments »

Horror and science fiction are the two genres that forked away from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. That story contained elements of both, but the forward-thinking optimism of science fiction warred against the regressive atavism of horror, and the styles went their separate ways.

Horror and science fiction are the two genres that forked away from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. That story contained elements of both, but the forward-thinking optimism of science fiction warred against the regressive atavism of horror, and the styles went their separate ways.

Some artists have wondered whether the genres are destined to combine again someday. What if the end product of science is horror? What if our increasing body of scientific knowledge is a Malthusian trap destined to destroy us? Pierre and Marie Curie discovered radium at the turn of the century. They thought they had found something benign and interesting – further developments produced a weapon that blasted 200,000 people to dust. We now live in an age of robotics and genomics – many dice are in the air, and who knows where they’ll land. While we wait, we might get a forewarning in the form of art. Certainly Frankenstein seems to have predicted a few things.

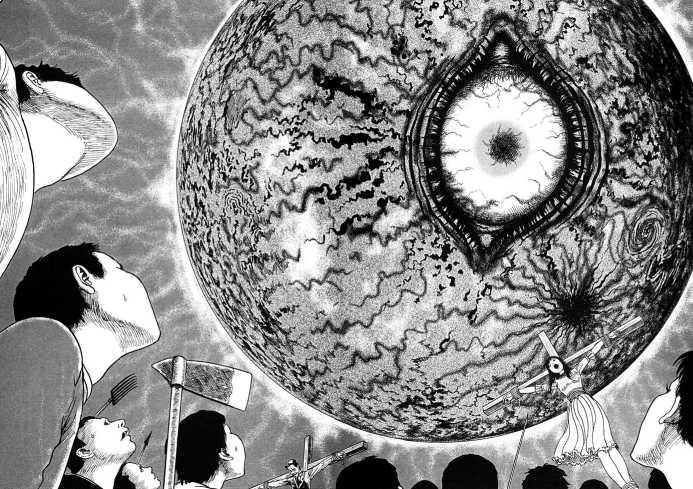

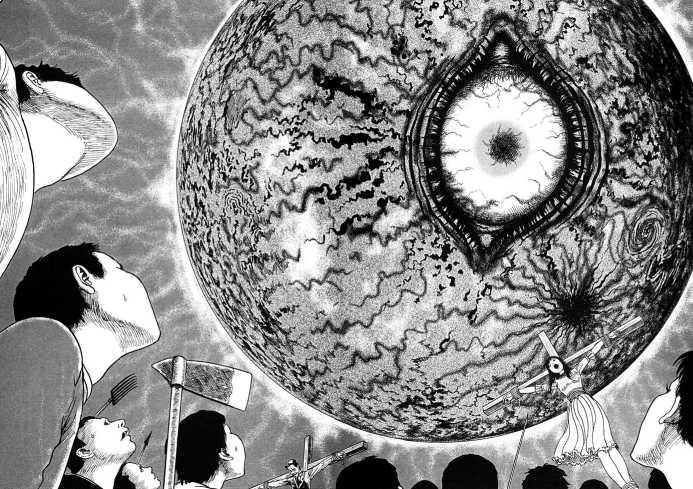

Hellstar Remina is a one-volume manga that Junji Ito created in 2006 that serves as a marriage of science fiction and horror set in a near-future earth. A strange planet has been discovered in the night sky, and it is on collision course with Earth. As panicking mobs tear cities apart, a group of people make a stand against the cosmic darkness filling the sky and the man-made darkness engulfing the the world below.

Remina isn’t as scary as Uzumaki or as revolting as Gyo, but it moves at a blistering pace, and if the story’s developments sometimes don’t make sense, at least you’re not given enough time to think about them. Without exaggerating, as much happens in Remina‘s one volume as happens in Uzumaki‘s three. Impressively, character development isn’t totally perfunctory, with a lot of cultists and greedy industrialists and whatnot. The end of the world means an end to consequences, and Ito documents mankind’s pathology to the full.

Remina is Ito’s most advanced work from an artistic standpoint. Buildings topple like dominoes, blast overpressure waves scatter crowds of people, and tsunamis engulf landscapes. There’s so much complicated and difficult art here, and all of it is rendered in Ito’s signature “organic” style. You’re a little scared to touch this guy’s drawings, his linework seems to be made of squirming bacteria rather than ink.

The bonus story “Army of One” is a welcome addition to the volume. A mysterious lunatic is stitching dead bodies together, and to make it worse. Very spooky and cool. Don’t waste time thinking about the ending – obviously not even Ito knows what it means.

Ito is a fan of sci-fi from way back…I’ve heard that his first creative effort was an abandoned SF novel in the style of Sakyo Komatsu. Hellstar Remina isn’t his best work, but it’s arguably the last 100% good thing he did for his fans, and a crazy ride to remember by any standard. Ito would soon lose his fastball and start creating boring Ray Bradbury ripoffs like Black Paradox. But for now, doomsday looms.

1 Comment »

What happened to this band, and what are the chances of it unhappening?

What happened to this band, and what are the chances of it unhappening?