Some electronic music is supposed to be danced to. Tangerine Dream’s 1970s albums are supposed to be anti-danced to. They are monoliths of sound and moving at all to them feels wrong: you can imagine Edgar Froese’s ghost staring in disapproval at your breath, and your heartbeat.

1976’s Stratosfear (their third major-label release on Virgin) sees the band changing. The first Tangerine Dreams were formless abyssic oceans of synthesiser noise with unusual sonic lifeforms flickering under the water (Alpha Centauri, from 1971, is the only ambient record I can think of that contains a drum solo). Once they signed to Virgin, their sound focused and tightened: Stratosfear, near the end of their classic period, has more overt melodies and rhythms. And unusually for early Dream, if you divide the running time by the number of tracks, you get a single-digit number.

“Stratosfear” is a forceful, climbing driving mini-epic, with a fun suspended/Egyptian pentatonic II melodic hook. It’s the most Vangelis-sounding track on the album. “The Big Sleep in Search of Hades” has less going on inside it, although there’s a fair amount of acoustic guitar for the prog rock fans. “3AM” has a slow-building intro that looks back to their earliest releases, though the tempo picks up soon after.

“Invisible Limits” is the longest track: 11 minutes of Pink Floyd worship with electric guitar and drumming, and a recurring pan flute motif. Tangerine Dream were the spacey, ambient wing of the German style of “krautrock”, and while some of this stuff is funky (Neu! Can, and certain Bowie songs circa 1977), Tangerine Dream is not. It cannot be emphasized enough that this music consists of bubbling 16th notes locked to a grid amid huge tidal waves of sound, and although it has some progressive rock influence (there are live examples of Edgar Froese attempting guitar solos, to dismal results), it has no groove at all. It’s what rock music would sound like if it hadn’t been influenced by jazz and RnB. The music is so white it’s #FFFFFF.

“Kosmische musik” (a term Froese coined) might seem very far removed from 80s hip hop, but they are both styles based upon a single piece of gear. For hip hop, it was the E-MU SP-12/SP-1200 sampler. For kosmische music, it was the modular synthesizer. Whether it was the Moog or the more portable EMS VCS, these synths and their sounds were everywhere in 70s rock. The sonic possibilities seemed endless. It’s not surprising that Tangerine Dream would adopt spacey-themes: synthesisers indeed seemed like a space-race breakthrough for music.

But this brought danger: were bands relying too much on (soon to be dated) technological wizardry? And yeah, a lot of early synth-powered music now provokes a reaction of “okay, there’s a delay effect on your notes. Is there anything here aside from that one trick, which can now be produced in 2 seconds with a VST and which I’ve heard a million times?” Like prog rock, it became a bloated scene, too in love with itself.

In the 80s, krautrock faded from prominence, and its ambient wing became a hundred fluttering feathers, all of them hoping to land in new markets. By the 80s, Jean-Michel Jarre was making synthpop, Vangelis was more famous for his movie soundtracks than his original albums, and Tangerine Dream were kind of playing it both ways. They toured heavily, in unconventional places. A 1974 performance at Reims cathedral (with Nico) ended in disaster. 6,000 tickets were sold for a 2,000-head venue, and hundreds of stoned hippies pissed against the historic stonework. I don’t think it’s normal for ambient musicians to get excommunicated by the Pope, but Edgar Froese managed it.

“Saintly man that he was, Father Bernard Goureau intoned more or less as follows: “It is true that the youth smoked marijuana in order to better enter into communication with Tangerine Dream’s sound and the spectacle at large; it is also true that others, to satisfy a natural obligation, urinated against the columns of the cathedral; and finally, it is again true that to combat the cold, couples were seen in kissing embraces. But it is equally true that some 6,000 young people, remaining sat upon the floor for three hours in the dark, had enjoyed the music and could have caused much more serious damage, with far less decorum.” Amen.”

Ambient synth-based music existed in a cultural blind spot in the 1980s: it was seemingly everywhere, but nobody listened to it. Or rather, they watched it instead of listening to it: it was deemed worthless unless accompanied by a laser light show or Blade Runner. Few people valued it as music, in and of itself. Tangerine Dream had journeyed out into space and found it to be a lightless dead end.

Ten years later, ambient would undergo a commercial resurgence (both Enigma’s “Sadeness: Part I” and The Orb’s U.F.Orb topped their respective UK charts at the start of the 90s), but it was a hip, modern ambient based on house music and samples, not long hair and synthesizer solos. Soon the world-crushing success of Enya sucked all the air out of that scene anyway. It’s possible that A Day Without Rain shifted more units than every Tangerine Dream album combined.

Tangerine Dream now seems old and quaint, like those probes we sent out in the seventies. Nothing ages as rapidly as the future. But in a weird way, their best music has a strangeness that stands outside age. They never wanted to be the mainstream, and even when they were () it seemed like a happy accident.

They were a German, and their English song titles – like their music – is bafflingly correct yet very odd. Stratosfear continues this tradition. “The Big Sleep in Search of Hades” suggests Raymond Chandler in the Greek underworld (does Philip Marlowe get paid two drachmas a day, plus expenses?), and “3 A.M. at the Border of the Marsh From Okefenokee”…shouldn’t from be to? All the words are spelled correctly, but it’s not English.

Tangerine Dream were never a band from Earth. I don’t know where they’re actually from, but their attempts to connect with the customs of our planet have the air of a mistake-filled travel guide written by aliens. They always had at least one foot in some alien world or another. Stratosfear is an excellent example of where they were, and charts some of the places they had still to visit.

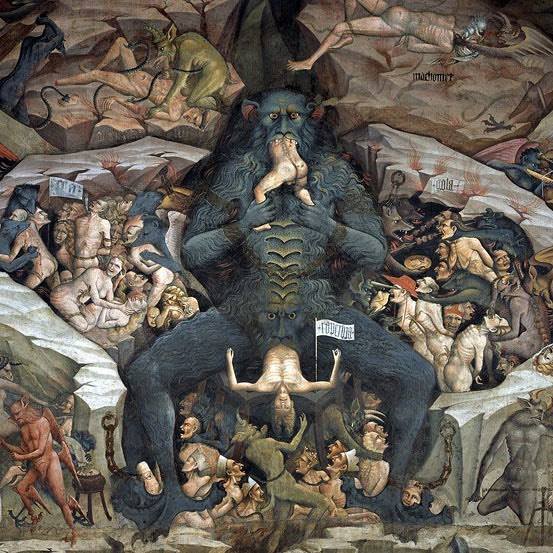

There’s an inaccessible, inhuman quality to a lot of this music. But it also challenges you to rise above your biological limits. Bigbrained people sometimes talk about “anthropomorphism”, or giving huge and mysterious concepts a human face. God is a bearded man. GPT-3 is the Terminator. The effect always diminishes whatever’s being spoken about: making the numinous and grand small and ugly. Humans are limited creatures in the end (which may be coming soon), and our horizons are very small. Tangerine Dream swaps the signified and the signifier. They dehumanize music, dehumanize space. They invite us to ponder a glowing, diaphanous eternity in which we never were.

No Comments »

The Japanese anime Fate/Stay Night contains this thought-provoking observation.

Is it true? Do people die if they are killed?

Famous people don’t. They leave parts of themselves behind in writing and memory, which survive their bodies. The desire for immortality is the driving force behind most art and all celebrity culture: a siren song saying that if you write or paint or expose your nipples in the right way, you’ll live forever.

But it’s a horrible form of life. A dead celebrity exists as a memory; a parasite clinging to a brain alongside thousands of other parasites. Time corrupts memories as well as flesh, and many dead people are “remembered” to life in a manner that would have astonished them.

But life as an undead cultural revenant is better that not existing at all. Even if we have misunderstood every word of Jesus of Nazareth, something of him exists inside the Gospels, quickening to life when they are read.

And if fame is the key to immortality, this creates a paradox, because a dramatic death increases the chance that you’ll become famous. Put another way, what would Jesus’s life have meant if he hadn’t died? Very little. He would have been just another anchorite preacher. The crucifix’s shadow lies like emphasis across all he said and did. Fate/Stay Night has it backward where Jesus was concerned: he lived when he was killed. He became immortal.

This is also true for Jesús, our subject today.

Not that they had much else in common. Jesús Ignacio Aldapuerta wasn’t Christ, n0t even by half.

Who was he?

Aldapuerta was a Spanish writer, medical student, mercenary, and sociopath.

He was born in Seville in 1950, and died in Madrid in 1987 in what appears to have been a suicide.

“…his partly cremated body was removed from his apartment, the building itself saved from conflagration by the unusually rapid arrival of the emergency services. The authorities took away various unburned books, documents – including what remained of his coded diaries, and finished and unfinished manuscripts – a small quantity of drugs, and the petrol canister that the police said was sufficient proof of self-immolation.”

He occupied his thirty-seven years of life with childhood, crime, prison sentences, medical school, and the writing of disturbing short fiction. He travelled a great deal to places such as Chile and the Philippines, though what he did there was a mystery.

“In his homeland, his chief income seems to have been that of a petty criminal, and served several prison sentences of theft and drug offences, the longest and most harrowing under Franco. What money he generated from his activities was generally spent on books, almost invariably pornographic, and prostitutes. His appetite for scatological literature began in his early teens, inspired by frequent visits to a bookshop in Madrid where he was introduced to pornographic pamphlets and the works of de Sade. The proprietor realized the strength of his interest and soon suggested trading volumes for sexual favours. Aldapuerta was perfectly satisfied with the arrangement and would “have the old man’s cock jabbing in my arse even when ready cash was available”, and even when the shelves contained nothing of worth he “sucked that foul Costilla de carno for abundant monetary reward”.

Aldapuerta enjoyed the golden age of travel – after plane and rail allowed fast travel across continents, but before tourism had ripped the flesh from the Earth’s bones. Aldapuerta saw many beautiful places before they were destroyed, but he wasn’t a beautiful man. The scant biographical information we possess is little more than a list of petty outrages and indignities…

“Aldapuerta spent two years at medical school where he learned the geography of the human body and something of its almost infinite capacity for suffering and degradation. He took especial delight in tending to the physically incapacitated and was thankful for the loose coats that “prevented the matrona from spotting the engorged cock that I would occasionally press against the bedridden patient”. […] Needless to say, he failed to complete his term at medical school.”

…and hints of far worse crimes, like glimpses of icebergs.

“There is no doubt that Aldapuerta had a fascination with human remains. Further to the incidents above, in 1976, he is said to have been detained at Spanish Customs when returning from a trip to Central America. He had $4000 cash in a hold-all, which he insisted was payment for mercenary activities. What alarmed Customers Officers more was the contents of a small package Aldapuerta carried under his arm. Inside were two dried human hands, which Aldapuerta said he had purchased form a trading post dealing in war trophies.”

“One other curious item found in his apartment, and photographed in the hands of a smiling policia, was an intricately carved dildo fashioned from the femur of a child.”

These quotes come from a book called The Eyes (1995, Critical Vision), which is a translated collection of Aldapuerta’s short fiction, along with a brief biography.

The book is long out of print, and a used copy of The Eyes will set you back $100-200 USD. A helpful Aldapuerta fanatic OCR’d the text and uploaded it online, which is where I first discovered it.

The Eyes has existed quietly for nearly thirty years. It has been cited in academic texts and used as a reference in true crime books. On 4chan’s /lit/ board and the dark web, people share the The Eyes the way they might drugs and illegal pornography (Aldapuerta’s writing would fit either category). I have done so four times. Aldapuerta’s mythos might actually be growing in the years after his death – he’s gaining more readers, reaching more people, perhaps inspiring more people. He might be more alive in 2023 than he was in 1987.

So what kind of book is The Eyes?

The Book

“The flies shrouded her in buzzing black, swirling up where my hands moved on her to reveal their eggs, dry white pearls against her moist red meat. I was stripping her to the bone now, scraping muscle from the thin struts of the framework on which she had hung herself and moved. Her face was still mostly intact, mask-like on the emptied vessel of her skull, expressionless and sleeping without pain as I sliced and tore her flesh away.”

It’s extreme and graphic. The stories are perverse, and cross many boundaries of violence and sex. I heard a joke once about a house that’s so dirty you wipe your shoes before you leave, and that describes what it’s like to enter Aldapuerta’s mind.

But there are other books like that. The interesting thing about The Eyes has always been its insane writer, and how little space seems to exist between Aldapuerta’s life and the things he wrote about. Most violent books are written by shy introverts, but the author of The Eyes isn’t putting on a mask; he actually is a maniac.

It’s also not clear that The Eyes is fiction.

A few stories are fantastical. Most are grounded and naturalistic, and echo known details about Aldapuerta’s life. They’re about mercenaries, and doctors, and thrill-seekers in the third-world; men in dark and violent places, scorning the laws of man and God. Many stories are written from the first person perspective, and almost all of the characters could be Aldapuerta himself.

The idea that The Eyes contains Aldapuerta’s subtly anonymized confessions is compelling and has been remarked upon many times throughout the years. Unreliable though The Eyes is, it’s the only window we have into a the life of a man we know little about – not even whether he truly died…

“Ironically, a rumour persists that the corpse carried from the apartment in 1987 wasn’t Aldapuerta at all, but his homosexual consort murdered and burned beyond recognition…”

The Stories

If we analyse these stories as fiction, their genre is uncertain. “Horror” comes close; “extreme horror” closer.

Some stories are political. “Indochine” involves a US soldier raping the body of a dead Vietnamese prostitute, with obvious Chomskyan parallels (synecdoche for the Vietnam war, et cetera). “A La Japonaise” is about a gang of libertines (identified only by Hebrew letters) who journey to a devastated village, ostensibly to provide medical aid, but actually to exploit the helpless survivors of a war that (it’s implied) they themselves started. “The Winnowing” says nothing and everything: it may be the most subtle story you could write about ethnic cleansing.

Some take a lighter touch. “Upright” is hilarious: a harassed teacher at a boy’s school tries to catch the perpetuator of a long-running prank – not to enforce school decorum, but so he’ll have an excuse to strip the offender naked and spank him. This tale echoes PG Wodehouse as well as de Sade.

Others seem written to test limits and get the author thrown in prison. In “Armful”, an obese pedophile is arrested and placed in a jail cell with his latest victim. He can’t be accused of a crime without an accuser, so he kills and dismembers the child, and over the course of one night, devours her entire body (including her bones) and defecates her out through a drain.

The two peaks (or abysses) of The Eyes are “Ikarus” and “Orphea”, where all the ingredients Aldapuerta trafficks in (decadence, surrealism, expressionism, sybaritism) swirl together, react, and produce flames.

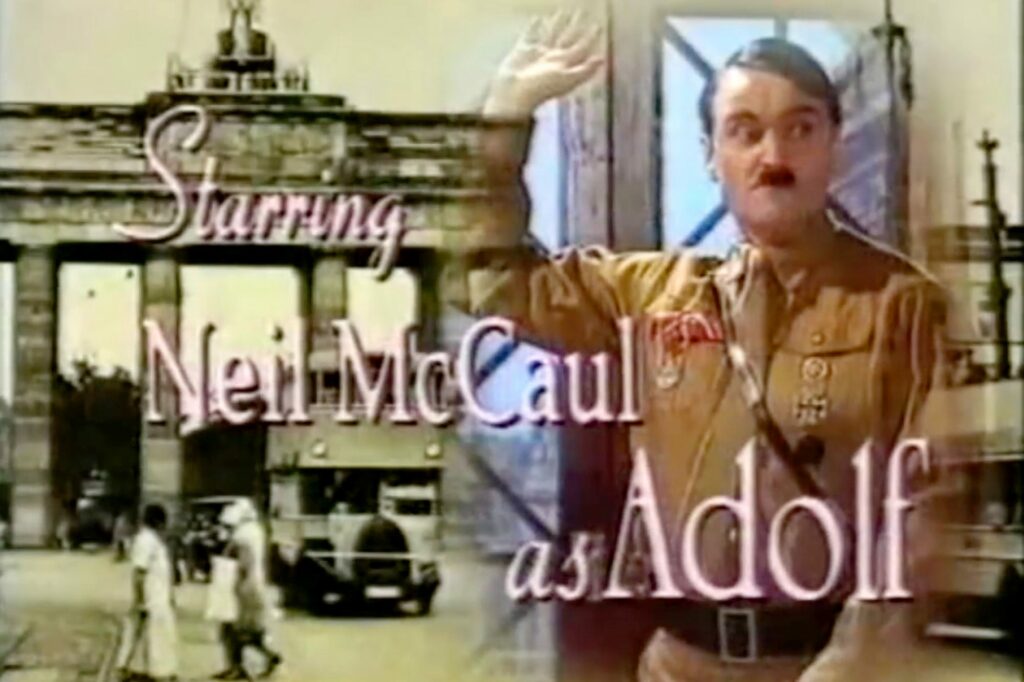

“Ikarus” has a World War II setting. A man steals a rocket-powered German Bachem Ba 349 and flies it directly into a plane, like a battering ram. I’ve heard people question the scientific accuracy of this, but that’s actually how the Ba 349 (or “Natter”) was supposed to be used. He blacks out (we don’t know whether into unconsciousness or death) and wakes up in a vast cathedral-like space, miles above the ground. There, he encounters something so repugnantly strange that I can’t describe it, no matter what words I use.

In “Orphea”, a man stalks a beautiful, famous blonde. He has a premonition that she’s about to die in a car crash, and undertakes a pilgrimage so he can be at her side, watching her flaming car. It’s a creepy story, and unlike JG Ballard’s Crash (which spends a lot of time explaining and justifying itself), we catch no glimpse of his motives. He seems completely soulless, an ambulatory videocamera. He watches, waits, and acts. A void lies behind his eyes.

It’s implied that the blonde woman is Jayne Mansfield (the story’s based on a famous urban legend), but Mansfield is overshadowed by an even more famous car accident and dead blonde. The events of the world are grim and repetitive: bloodshed yesterday, bloodshed tomorrow. It’s not hard to predict the future: it’s actually harder to not do it.

The Eyes has other things you wouldn’t expect: Aldapuerta probably has a classical education. “The Sand, The Sand!” is a reference to the cry raised by Xenophon’s army when they saw the black sea. “Ikarus” and “Orpheus” are figures from Greek mythology. There’s a recurrent interest in language. And although it’s supposedly translated from Spanish, it doesn’t read like translated prose, which is usually taxidermied and dead, ruined by a translator’s quest for “textual accuracy”. The Eyes seems to contain a beating heart, irrigated by flowing blood. Maybe it’s syphilitic.

Extreme horror is a unimpressive genre, which is saying a lot for a genre that wants to be in the gutter. Upward of 95% of it (including alleged “classics” such as Richard Laymon’s The Cellar) are about as readable as half-chewed vomit: I sampled one for this essay and gave up a few paragraphs in. “Ryan lowered his head and stared down at his lap, twiddling his fingers as if he were having a thumb war with himself.” Life’s too short to read shit books.

The Eyes, by contrast, is very well written. Few words are wasted. It knows the effect it wants to achieve, and rips it from your guts. Its worst prose has the stripped-back efficiency of crime scene reportage. Its best seems to razor your eyeballs open when you read it.

Certain Jews, in Nazi work camps, concealed jewels by swallowing them, defecating them out, swallowing them again, and so on. The Eyes reminds me of that: gems swimming in fecal matter. For fans of good writing, the stories emit a ghastly, revolting shine. How badly do you want them?

Who Is He?

Maybe you’ve realized that something’s not right.

Aldapuerta is not real; and cannot be real. There’s absolutely no record that he ever lived, apart from The Eyes. No birth or death certificates, no police reports, no relatives selling stories to tabloids, no provable details at all. Nothing.

The world is starved for monsters. There’s a 28,000 page wiki documenting the life of a man whose main claims to fame are drawing a bad Sonic the Hedgehog recolor and having sex with his mother. If Aldapuerta existed, there would have been multiple BBC true crime docudramas made about him by now.

His life (Catholic education, teenage corruption, drugs, prison, death) is suspiciously convenient, and too littered with serial killer cliches (he flunked out of med school, he possesses mementos of his victims) to be believable. Real lives wander around like rivers, contorting and twisting. Aldapuerta’s life is more like a trench dug in a straight line by an excavator. It’s not a lived life, it’s a manufactured one.

The book is supposedly translated from Spanish, but there’s an telling lack of prior publisher, release date, year of copyright, and so forth. It’s virtually certain that the 1995 “translation” by Critical Vision is actually the book’s original printing.

The things “Lucia Teodora” (who also doesn’t exist) writes stuff about “coded diaries” and Aldapuerta not being dead is a lifeline, in case the author wanted to publish more “Aldapuerta” material.

So, who really wrote The Eyes?

James Williamson (a one-time book publisher and currently hiding from justice in Thailand), and Jeremy Reed (an odd poet) are sometimes feted as potential authors. In truth, it’s a small press author called Simon Whitechapel.

The Sin of Simony

He is a British small press author, and although he’s very much alive, he’s a difficult man to keep track of. He has used many identities and names: Amygdala, Kopfwurmkundalini, Krilling for Company. His various biographies around the internet are littered with false details and jokes. You may have spoken to him already, without realising it.

There’s two ways to hide your identity: tell people nothing, or tell people everything: amplifying the signal into a white blast of noise. Whitechapel uses a mixture of the two approaches.

He traffics in constructed identities and worlds. At the moment, he blogs at “Overlord In Terms of Core Issues Around Maximal Engagement with Key Notions of the Über-Feral” (don’t ask – there’s at least five layers of jokes in the blog title). Inside you will find recreational mathematics, book reviews, philosophical essays, and quotes from the Guardian. It’s like a blog from an alternate universe. There’s a lot of calculated weirdness, and things that almost make sense. For example, he’s given to posting albums he’s listening to (in the manner of BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs). Almost all will be fictitious, but there’s always one real album on the list. He links to websites that don’t exist.

There are more ways to be perverse than to drag a razor through flesh. What Aldapuerta is to blood, Whitechapel might be to pneuma, or to logic.

He published fiction in the early 90s through various small presses. His first book is The Slaughter King (published 1993 by Bad Blood, although it would later be reprinted by Critical Vision, the same house that published Aldapuerta). It details a policewoman’s hunt for a serial killer, and is essentially Atalanta’s hunt for the Calydonian Boar written as a violent police procedural. Other short stories from the early-to-mid 90s include “Walpurgisnachtmusik” in DM Mitchell’s The Starry Wisdom, and “Xerampelinae” in James Williamson’s Dust – A Creation Books Reader.

Read any of these stories, and you’ll immediately recognize the writer of The Eyes. The prose style is the same. They’re violent and transgressive, but written with a craft that elevates the material. He often draws from the same creative wells. “Orphea”‘s motif of a static-obsessed psychopath and “BVM”‘s religious blasphemy are both found The Slaughter King. “Xerampelinae” involves an educated but sexually depraved Colombian detective called Bacco di Corona, who isn’t wholly unlike Jesus Ignacio Aldapuerta. This story is supposedly from an unpublished (and never-published) collection called DCLXVI. It’s not unthinkable that this collection was an early version of what became the stories from The Eyes, or that Bacco di Corona is a larval version of the Aldapuerta character.

As years passed, Whitechapel’s interests drifted. In 1997, he released the essay collection Intense Device (“An exploration of dildos through the ages, the life and crimes of Marquis De Sade, the literary twilight that is the TV and movie tie in, the Christian Crusader Comics and more”), and Crossing to Kill, (a true-crime book about the femicides of Ciudad Juarez that, hilariously, cites Aldapuerta as an authority on the sociopathic mind!). He also published large volumes of fiction on the internet, but it was often pastiches of authors such as Clark Ashton Smith, HP Lovecraft, and MR James.

In later years, Whitechapel has become fairly open that Aldapuerta was his assumed identity. The joke becomes painfully obvious on his blog, with Whitechapel having him respond to reviews via an Ouija board.

Whitechapel’s final work (unless he’s publishing under a different name) is Gweel, which is as bizarre as The Eyes but in a very different way, owing more to Borges and Calvino than de Sade. In Gweel, there are stories involving planets being arrested for crimes, as well as a “story” written entirely in Magic Number Puzzles.

Again, this feels transgressive at a deeper level than Aldapuerta. Drive a razor through flesh, and you’re still accepting rules about flesh and steel. You’re not supposed to cut people, but you are. The irony of splatterpunk books is that they actually reinforce the traditional morality they’re tilting against (such acts are only shocking if they’re abnormal, and illicit) But Gweel chooses larger targets: science and mathematics. That’s the essence of surrealism, to me. Taking the biggest, most familiar aspects of the universe and imagining the ways that they might be different.

By the way, Simon Whitechapel is not real either, anymore than Aldapuerta is. Who is he really? If my guesses are correct, he’s wise not to reveal himself.

The Other Aldapuertas

Whitechapel didn’t create the Aldapuerta character out of whole cloth. He couldn’t have.

There’s a number of historical personalities that bear a striking similarity to the mad, mythical Andalusian. Sometimes the similarities are deliberate, other times accidental.

De Sade is too obvious an influence to merit detailed discussion.

Pier Pasolini is another possible one: an Italian writer, poet, and filmmaker who was murdered in 1975 (although the circumstances of this are quite cloudy). His main legacy is the neo-Fascist nightmare Salo, inspired by 120 Days of Sodom, and when he died he was working on an extremely long and nearly unreadable novel called Petrolio (which, like 120 Days of Sodom, exists mainly in outline form).

From Wikipedia:

“Pasolini was murdered and possibly assassinated on 2 November 1975 on the beach at Ostia.[60] He had been run over several times by his own car. Multiple bones were broken and his testicles were crushed by what appeared to be a metal bar.[61] An autopsy revealed that his body had been partially burned with gasoline after his death. The crime was long viewed as a Mafia-style revenge killing, one extremely unlikely to have been carried out by only one person. Pasolini was buried in Casarsa.

Giuseppe (Pino) Pelosi (1958–2017), then 17 years old, was caught driving Pasolini’s car and confessed to the murder. He was convicted in 1976, initially with “unknown others”, but this phrase was later removed from the verdict.[54][62] Twenty-nine years later, on 7 May 2005, Pelosi retracted his confession, which he said had been made under the threat of violence to his family. He claimed that three people “with a Southern accent” had committed the murder, insulting Pasolini as a “dirty communist”.[63]”

Both Pasolini and Aldapuerta were:

- Gay

- Raised religious

- Writers of transgressive literature

- Inspired by de Sade

- Non-sympatico with the conservative powers of their native countries

- Killed in a manner involving fire

- Religiously-named (Pier is an Italian variant of Peter, or the name Jesus gave to Simon Bar-Jonah)

- Working on a huge, unfinished final masterpiece when they died

I have no idea whether the simularities were intended. Roll enough dice and patterns appear on their own.

A third man is Géza Csáth, an insane Hungarian doctor who is worthy of an article on his own.

Csáth was born József Brenner in 1887. In his youth, he was a musician who loved Kodály and Bartók. He wrote from an early age – music criticism at first, and then prose that would be classified as romantic decadence.

He became a doctor in 1909, and worked as a neurologist at the prestigious Budapest research clinic. He seemed to have the acquired the trappings of a successful life in his early twenties.

It is known that Csáth began taking morphine in 1910 (out of scientific curiosity, he said). He became an addict, and soon his promising career began to falter. In his latter years, he was mainlining large quantities of morphine and Pantopon each day while working in a series of country spas.

His self-destruction is vividly described in The Diary of Géza Csáth (tr. Peter Reich, Budapest: Angelusz & Gold), where he describes his daily life (mostly, doing drugs, and deflowering a neverending series of female patients). As with Aldapuerta, I’m struck by the sense that this account is partially fiction. The amount of drugs he consumes would seem to inhibit accurate recollection, and it’s implausible that he could have raped dozens of upper-class women without getting fired (or, in an age when men wore schläger scars on their cheeks, killed by a vengeful husband.)

He became a married man in 1913 – one wonders if Olga Jónás, his wife, knew what she was getting herself into – but his uxorial happiness would not last. War broke out in 1914, and Csáth was drafted into the Hungarian army. His worsening addiction meant a medical discharge, by which point he’d begun to collapse into utter insanity. He was not able to re-integrate into society.

In 1919 he murdered his wife with a revolver (remind you of anyone?), and attempted suicide by poison and wrist-slitting. His life was saved, but facing psychiatric imprisonment, he attempted suicide again, this time successfully.

His diary spares no detail of his physical decline.

“…in my weak and forever veiled voice, my steady staring in the mirror, my cynical and shrunken penis, my drawn face, my witless conversation, my impotent, lazy life, my suspicious behavior, my insolence with which I lengthily disappear into the WC, my stupidity…. I also think that I stink, because with my sense of smell impaired, I can no longer smell the stench of my poorly wiped asshole or the mouth odor caused by my rotting teeth.”

This reminds me of a passage in Aldapuerta’s “A La Japonaise”.

“…Forgive me. I am a boring old fart. A cancer-riddled, boring old fat. As I lie here in darkness, whispering into the microphone, my body seems to reveal its secrets, faecal lumps of cancer fluorescing through the melting transparency of my flesh, pouring their poisons into the clogging reticulation of my veins and arteries. They are clustered thickest in the uro-genitary region, as though feasting on the afterglow of the energies I once regularly roused there. I piss, shit blood. Either act of excretion (mostly they are combined) seems to slit me like a razor. I weep involuntarily and my mouth tastes like sour rust. Even farting is agony. It is most interesting.”

The corruption of age is terrible. Father Time is Aldapuerta to us all.

Csáth’s fiction is also evocative of Aldapuerta’s. A translated copy of Opium and Other Stories reveals a man drawn to vileness and brutality, often to an excessive degree. For example, “Matricide” is about a pair of boys who torture animals, and then “graduate” to human beings.

“The dog’s chest would be slit open, its bleeding blotted as they operated and listened to the animal’s terrible, helpless moans. They would stare at its beating heart, take the warm, throbbing little mechanism in their fingers and destroy first the sac, then the chambers with tiny stabs. Their curiosity over the mystery of pain was insatiable.”

And here’s Aldapuerta on that same mystery.

“Consider the capacity of the human body for pleasure. Sometimes, it is pleasant to eat, to drink, to see, to touch, to smell, to hear, to make love. The mouth. The eyes. The fingertips, The nose. The ears. The genitals. Our voluptific faculties (if you will forgive me the coinage) are not exclusively concentrated here. The whole body is susceptible to pleasure, but in places there are wells from which it may be drawn up in greater quantity. But not inexhaustibly. How long is it possible to know pleasure? Rich Romans ate to satiety, and then purged their overburdened bellies and ate again. But they could not eat for ever. A rose is sweet, but the nose becomes habituated to its scent.

“Yet consider.

“Consider pain.

“Give me a cubic centimeter of your flesh and I could give you pain that would swallow you as the ocean swallows a grain of salt. And you would always be ripe for it, from before the time of your birth to the moment of your death, we are always in season for the embrace of pain. To experience pain requires no intelligence, no maturity, no wisdom, no slow working of the hormones in the moist midnight of our innards. We are always ripe for it. All life is ripe for it. Always.”

I could mention other names, such as Don Juan, or Nat Tate (a hoax artist who was invented in 1998 by William Boyd and David Bowie). Suffice to say, it’s no credit to the human race that so many versions of Aldapuerta spring up like dragon’s teeth.

But then, the world is a big place. It’s hard to create a life that hasn’t been partially lived by someone else. Or, as Pasolini shows, die a death that hasn’t been died by someone else. Aldapuerta, while dead, is also alive. And while fictional, he’s also real. Reality and truth both echoe in this dark, nearly forgotten book.

There’s no big reveal, or insight about the human condition. Aldapuerta causes me frustration. Thinking about him is like being unmoored in a hurricane, tugged further and further into an endless wind. He does provide a good example of an urban legend: countless people online have been tricked into thinking Aldapuerta’s real. But have they been tricked? Urban legends are fake yet true. They fascinate us because of how clearly they evoke the conditions of the world.

“American troops in Vietnam, he said, had “raped, cut off heads, taped wires from portable telephones to human genitals and turned up the power, cut off limbs, blown up bodies, randomly shot at civilians, razed villages in fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan, shot cattle and dogs for fun, poisoned food stocks and generally ravaged the countryside of South Vietnam in addition to the normal ravage of war, and the normal and very particular ravaging which is done by the applied bombing power of this country.”

“For seven months, Tiger Force soldiers moved across the Central Highlands, killing scores of unarmed civilians — in some cases torturing and mutilating them — in a spate of violence never revealed to the American public,” the newspaper said, at other points describing the killing of hundreds of unarmed civilians. “Women and children were intentionally blown up in underground bunkers,” The Blade said. “Elderly farmers were shot as they toiled in the fields. Prisoners were tortured and executed — their ears and scalps severed for souvenirs. One soldier kicked out the teeth of executed civilians for their gold fillings.”

Maybe hell doesn’t exist. But we have dug into the ground and built one ourselves.

No Comments »

It often takes time to “get” a band. It’s like being at a petrol station, and you’re waiting for petrol to flow through the pipe. You can’t rush it. You have to wait for that lovely moment we all enjoy, when cool, delicious petrol goes squirting into our mouth, nose, and eyes.

When I started listening to The Fall, I had my reaction planned out like a chemotherapy plan: I’d hate them at first, slowly hack away at their thirty-one-album discography, and then they’d become one of my favorite bands.

Instead, the opposite happened. I loved them at first. Then I didn’t.

The Infostainment Scam (or whatever it’s called) was a good first choice. It has several excellent songs; the disco apocalypse of “Lost in Music”, the psychotic noir prison-bar rattling of “It’s a Curse”, and the brightly Gary-Glittering stomp of “Glam-Racket”. Its aesthetic of barely-marshalled noise was exhilerating, and although Mark E Smith’s vocals sounded like a drunk co-worker overconfidently singing karaoke, surely this would prove an acquired taste.

Then I listened to more The Fall albums. They left no impression, or were memorable for bad reasons.

Hip Priest and the Kamerads sounds like slam poetry delivered over noise rock. The title track was eight minutes of blues rock choogling: annoying and borderline unlistenable. Bend Sinister is more of the same: songs that make their point after a minute and then continue for another six. Their version of “Victoria” is one of the least necessary covers I’ve ever heard. They changed nothing. Is this where post-punk was at as a genre in 1988? Reverential, straightfaced covers of boomer rock anthems?

Soon I was growing bored with The Fall. They seemed all vibes, no substance. But maybe the problem was me. After all “Lost in Music” was proof they could write great music…then I took a closer look at The Infotainment Scan’s songwriting credits, and said “ok then.”

Then there’s Mark E Smith, the band’s alleged singer.

Rock journalists love guys like Mark. He’s a walking cliche and is very easy to write about. Just arrange “consummate perfectionist”, “complex personality”, “troubled genius”, “enfant terrible”, “provocateur”, “outsider artist”, “incendiary maverick”, “Janus-faced,” “checkered career” in some order like fridge magnets, and you’ve written your own MES bio.

But there was a man beneath the cliches, a man who’s troubling to come to terms with. Here‘s guitarist Ben Pritchard, who got to know the “troubled genius” firsthand.

Physical violent attacks are not we should have to deal with on a daily basis. […] We shouldn’t have to be worried that the singer’s going to attack us again before the gig because we’ve stopped off for a hotdog at the service station. Like we’re wasting time… fucking hell we can’t do anything. You can’t eat, if you went for a meal even on your day off, you’d come back and he’d be waiting for you ‘What you fucking doing? What you fucking doing, eating? Fucking useless cunts.’ What? I’ve gotta eat, me. He puts you down for getting hungry!

[…] when we went to America it just got worse. […] we can only rely on each other to get ourselves out of the shit. Cos Mark could fucking leave us – and he did on the tour in America with the broken leg, he left us with no fucking money, no flight tickets home, he just fucking left us. We had to start getting deposits back for the hire vehicles, we had to get money together for our flights to Chicago. Our flight to Chicago was a non-refundable ticket that wasn’t due for two weeks. He didn’t care, he had all the money from all the gigs. He had Ed Blaney with him, he had his wife, they got home fine, no problem.

It’s obvious by now that the UK music press will excuse obnoxious or abusive behavior if it makes a good story. They were happy to interpret MES’s abhorrent personal behavior as something romantic: a striving toward perfection, marred by silly foolish humans like Pritchard who are the sand in MES’s gears.

“Talented asshole” is a more fitting descriptor, particularly with the first part spoken in a sarcastic voice. Most such assholes aren’t talented, we just pretend they are, because how else to justify the position we’ve given them in our culture? The hardest person to talk out of a scam is the person who’s just been rooked by one, and MES spent decades running a scam on the British press.

Quoting Wikipedia: “Smith’s approach to music was unconventional and he did not have high regard for musicianship, stating that ‘rock & roll isn’t even music really. It’s a mistreating of instruments to get feelings over’.” That sounds like a clever defense for not understanding music. But it gets recontextualized as “unconventional”.

Or witness this desperate attempt by Spin to recast MES as a modern Oscar Wilde, full of cutting put-downs and scathing one-liners. He thought Telly Savalas was “a twat”! He thought new bands were a bunch of “ass lickers”! Oh, and wait until you hear what he did to Mumford & Sons. Ready? He threw a bottle at them, the absolute lunatic! If you or I did something like that, we’d be on r/madlads getting ridiculed.

Ben Pritchard’s interview goes on and on, listing all kinds of grubby, exploitative nonsense. But even that could be excusable if MES was a brilliant talent. After all, David Bowie was occasionally given to sharp business practices.

But here’s the part that made me decide not to bother with Mark E Smith or his music.

I’d only been playing the guitar for about two years. It was the day after I’d bought my Stratocaster that was. So that was like the first time I put it on and played it properly and plugged it in was in front of [Mark] in the studio, listening to the backing track of Dr Buck’s Letter. He says, “Go on, cock. Just fookin play something, I’m going to the pub.” And that was it…

“Just fookin play something, I’m going to the pub.” That seems to be the Rosetta stone of MES: sneering, lazy disinterest. Yeah, who cares. Just play something. Rock music is for idiots. Have contempt for your bandmates, and contempt for your fans.

MES wasn’t a consummate perfectionist, slaving to reach some Promethean ideal. He was a jerk who threw together careless, slapdash music with whoever was willing to tolerate him. Or so it seems to me.

Sometimes The Fall could be good. Perhaps they were often good – there are big parts of their discography I haven’t touched. But I am sure that while they were being good, MES was getting drunk at the pub.

MES could write some obtuse and weird lyrics, and I enjoy his song titles. They’re kind of broken and not-quite-right, like a cracked plate. “Paranoia Man in Cheap Sh*t Room”. That’s a great title. But it’s all just alcohol-inspired brilliance: random, loose puns, joined together in disorder by misfiring dendrites. I was once at a Tab in Sydney, and heard a man order a Sprite. When asked to justify himself by his mates (who were all several pints in on VB and Carlton Dry), he sagely said “Sprite makes right.” That man is 3 IQ points from writing The Fall lyrics.

MES is not a treasured national resource for supplying us with beermat philosophy. You can find people who think and act like him down at the local pub. They exist in huge quantities.

In fact, I don’t see any sign that MES had any worthwhile qualities. Yes, occasionally, he could be nice to his bandmates. You could call this “complex”, or you could realize that if he was nasty all the time, nobody would work with him.

MES didn’t write music, couldn’t play an instrument, “sang” only in the loosest of terms, and fuck knows he wasn’t pretty to look at. What is this violent alcoholic retard good for?

No Comments »