Michael Jackson’s recording career came to a sad conclusion on October 30, 2001. He should have released Invincible in September, when it would have only been the second greatest tragedy of the month.

It’s not an album, it’s a PR statement: “don’t listen to what everyone’s saying about me. I’m a normal guy!” By 2000 Jacko’s public image was absolutely out of control and he’d had two options: either rebrand himself as a Howard Hughes-type freakshow, or tamp down the weirdness somehow.

He made the boring choice, or perhaps Sony made it for him. The label had a lot invested both in Invincible’s success (its thirty million dollar production cost remains an industry record, though Michael demanded still more money and accused CEO Tommy Mottola of racism when he wouldn’t pay), and in its main star not appearing like a total lunatic. Before anything else, this album tries to not rock the boat, and unfortunately it succeeds.

Invincible wants to be vapid millennial R&B and follows a formula. Ballads, soft strings, “edgy” songs containing glitched-up funk beats and rapping, guest spots by normal wholesome dudes (ie, R Kelly), lyrics spat out by a Platitude Bot 2000, and when ideas run out (almost immediately) still more ballads. Most albums are accidentally forgettable. Not so here. Invincible was conceived and executed with that goal in mind.

The biggest problem with Invincible – aside from the fact that there’s nothing creepier than a man loudly insisting that he’s normal – is that it’s extremely dull. Who wants to hear a former titan ripping off people who were ripping him off to begin with? The lyrics (aside from “Privacy” and the nauseating “The Lost Children”) are just all about love and romance, and the music just blurs into Boyz II Men (emphasis on the boys, I guess).

Sony was heavily invested, but the same can’t be said for Michael. He barely seems to be in the studio, and he projects not an iota of coolness or attitude into these songs (which aren’t worthy of them in any event). He moon-shuffles. He’s a Smooth Criminal whose offense is an unpaid parking ticket, a Speed Demon doing 62 in a 60 zone. I aspire to someday be this indifferent to thirty million dollars landing in my checking account.

Needless to say, he didn’t tour off Invincible, sparing us the comedy of seeing “You Rock My World” on a setlist with “Don’t Stop ‘Till You Get Enough”. He made a few media appearances. For example, in 2003 the deputies of Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Dept got a unique meet-and-greet photo session when Mr Normal was charged with seven counts of child sexual abuse.

His songwriting talent had already started to crumble on HIStory and here it’s completely gone. Sixteen bad songs. No good ones. If you want to hear music like “Billie Jean”, you’re in luck. In 1982 Michael Jackson released an album called Thriller, and by sheer coincidence it has a song that sounds exactly like “Billie Jean”! It even has the same title! Don’t listen to this album, though. It’s shit.

I am sorry if I seem to dislike Michael personally. I actually don’t understand him at all. The more I learn and read and expose myself to his personality, the more my noncomprehension deepens. There’s something alien and unreachable about him. But I am repulsed by the parts I see: the glimpses of squirming tentacles behind an impenetrable shell.

I am strongly persuaded that he molested children. This casts much of his character (his philanthropy, his generosity) in a different light: the deeds of a manipulator trying to escape consequences. It makes his war against the paparazzi far less sympathetic. I hear “You keep on stalking me, invading my privacy. Won’t you just let me be.“, remember Robson’s story about finding bloodstains in his underwear, and accept that maybe Michael’s privacy should, in fact, have been invaded. The paranoid tenor of his later work seems less fanciful: it was no delusion, because Michael actually had everything to hide.

His fans are awful. He was incredibly talented as a musician, but in the 90s this talent was eclipsed by a different skill: building and leading a kind of cult. He is a fascinating example of a secular religious icon, and to this day, living Thriller zombies haunt Twitter and Tiktok, circulating his apologetics. The basic thrust is that everything that went wrong for Michael – his finances, his appearance, his death – was someone else’s fault.

There’s a grain of truth to this. Michael Jackson never had a chance at living a normal life. But his fans ignore Michael’s agency (and four hundred million records sold buys a lot of agency), objectifying him to the level of a puppet.

Did Conrad Murray cause his death? Yes, the Jackobots say. He gave him surgical anesthetic as a sleeping aid! Bad doctor! They don’t ask the next question: who hired Conrad Murray to do this? Answer: Michael. They also don’t ask what would have happened if Murray had refused this stupid and insane order. Answer: Michael would have fired him, and found a different doctor.

The same can be said for the ruin of Michael’s face, his oversized chin implant, the nose whittled away like a blade, etc. Unneeded operations. But what would be the point of a plastic surgeon refusing to perform them? Michael had endless money to indulge his body dysmorphia. He would just go to someone else. The problem was always Michael. His story is one of tragedy, victimization, and self-destruction.

But self-destructive people can make fascinating art, and this was Michael’s saving grace. I’d like to pretend his recording career ended with HIStory. That album, like the one before, was a paranoid, sweaty jumble of blame-laying and resentment. Disturbing though it was, it made for compelling listening. You felt you were getting ringside seats for a man’s breakdown, and you got some strong songs, too: “Scream” and “Stranger in Moscow” kick the shit out of everything on this album. There’s a class of words in English better known by their opposites (gruntled, hinged, domitable, and so on). Michael Jackson’s last album is very vincible indeed.

No Comments »

I’ve had it with this dump. We got no food, we got no jobs, our pets’ heads are falling off, and now it’s time to talk about the prose of Stephen King and Dean Koontz.

They are two of the highest-selling authors of our time. They’ve sold thousands of books, maybe tens of thousands. You might not like either them, but clearly they’re doing something that works.

Stephen King

The word that captures King’s prose is “conversational”. His writing has the relaxed, chatty quality of a neighbour telling you about his day.

“The terror, which would not end for another twenty-eight years – if it ever did end – began, so far as I know or can tell, with a boat made from a sheet of newspapers floating down a gutter swollen with rain.”

That’s the opening sentence of It. Note the elliptic, rambling style. The way it’s loaded with clauses. The self-conscious hedging of “so far as I know” and “if it ever did end“.

This is how people talk in real life. They don’t move in a straight line toward the point: they wander, they misspeak, and they double back and have to correct themselves. Record yourself talking sometime.

The stumbling “if it ever did end” is especially good: it’s like the guy’s still getting the story straight in his head. It perfectly suggests the dark, turbulent glass of a human mind, and grounds the story in reality.

Why does this work? Remember that stories were communicated orally for the majority of human history. We’re the odd ones out by reading books in the third millennium. “Pulped trees imprinted with thousands of black letters” is not a particularly natural way to consume stories, and it forces the reader to do several awkward deciphering acts. Black letters must be decoded into images, and those images unpackaged into setting, tone, characters, subtext, and so forth. Anything that can shortcut this process – making the images bloom faster, or shine brighter – is a mitzvah. King hardwires his story directly into your subconscious by making it sound like it’s coming out of a living person’s someone’s mouth.

Furthermore, King is a horror author, and horror isn’t about scary clowns and haunted cars, it’s about the contrast of states – normal against abnormal, sane against mad, dead against alive. A dead body starting to walk is only disturbing in a universe where that isn’t supposed to happen. A character’s descent into madness is only meaningful in a world that presupposes sanity. A lot of bad horror fails because it plunges you into the deep end too quickly. Everyone’s dead, everyone’s insane. We don’t get a sense of normalcy being ruptured.

As King understood forty years ago, “Monster in a little town” isn’t spooky because of the monster, it’s spooky because of the little town – the idea that normal, wholesome life has gone wrong.

And so he’s starting the story in the most normal way he can: a chatty, avuncular older relative, telling you about a sheet of newspaper floating into a gutter.

Dean Koontz

Dean Koontz is often regarded as Stephen King’s peer. They are shelved together, read by the same people, their parents conspired to have their surnames both start with K, etc. King/Koontz are potentially the world’s most famous duo in the world where neither member has ever had anything to do with the other.

But his prose is massively different; heavy where King’s is easy, concise where King’s is garrulous. Koontz has spoken about his writing process before.

I work 10- and 11-hour days because in long sessions I fall away more completely into story and characters than I would in, say, a six-hour day. On good days, I might wind up with five or six pages of finished work; on bad days, a third of a page. Even five or six is not a high rate of production for a 10- or 11-hour day, but there are more good days than bad. And the secret is doing it day after day, committing to it and avoiding distractions. A month–perhaps 22 to 25 work days–goes by and, as a slow drip of water can fill a huge cauldron in a month, so you discover that you have 75 polished pages. The process is slow, but that’s a good thing. Because I don’t do a quick first draft and then revise it, I have plenty of time to let the subconscious work; therefore, I am led to surprise after surprise that enriches story and deepens character. I have a low boredom threshold, and in part I suspect I fell into this method of working in order to keep myself mystified about the direction of the piece–and therefore entertained. A very long novel, like FROM THE CORNER OF HIS EYE can take a year. A book like THE GOOD GUY, six months.

And he revises heavily. He uses a computer now, but once used a typewriter, and piled up fearsome amounts of wastepaper. If pages were people, Dean Koontz would be eating his last meal on death row right now.

My wife, Gerda, had been urging me to trade my typewriter for a computer. When I finished WHISPERS, she informed me that she had tracked our office supplies, and that for every page in the final manuscript, I had used thirty-two pages of typing paper, which meant that I had done thirty-one discarded drafts of every page, typing eight hundred pages of text again and again to polish it. Although I was aware of my obsessive-compulsive rewriting, I hadn’t realized quite how many revisions I usually undertook.

Here are the results of that [excerpts from the first few pages of The Taking].

A few minutes past one o’clock in the morning, a hard rain fell without warning. No thunder preceded the deluge, no wind.

The abruptness and the ferocity of the downpour had the urgent quality of a perilous storm in a dream.

Lying in bed beside her husband, Molly Sloan had been restless before the sudden cloudburst. She grew increasingly fidgety as she listened to the rush of rain.

The voices of the tempest were legion, like an angry crowd chanting in a lost language. […] Beside her, Neil snored softly, oblivious of the storm.

Sleep always found him within a minute of the moment when he put his head on the pillow and closed his eyes. He seldom stirred during the night; after eight hours, he woke in the same position in which he had gone to sleep–rested, invigorated.

Neil claimed that only the innocent enjoyed such perfect sleep.

Molly called it the sleep of the slacker.

Throughout their seven years of marriage, they had conducted their lives by different clocks.

She dwelled as much in the future as in the present, envisioning where she wished to go, relentlessly mapping the path that ought to lead to her high goals. Her strong mainspring was wound tight.

Neil lived in the moment. To him, the far future was next week, and he trusted time to take him there whether or not he planned the journey.

They were as different as mice and moonbeams.

You’re watching condensed sweat when you read his prose. It’s sparse and best-sellery, but every word choice was labored over.

Koontz’s prose has a lyrical aspect. It’s full of assonance and alliteration – notice that Koontz runs words with similar sounds or syllables close together (lost language…sleep of the slacker…mice and moonbeams). This consonance triggers the phonological loop that helps anchor phrases in memory, which is why it’s so common in advertising slogans (“Heinz means beans”). It might seem strange that Koontz’s Flannery O’Connor-inspired prose would share a link to advertising culture, but there it is.

Yes, it’s purple, sometimes excessively so. “Mice and moonbeams” is maybe too far. But it’s also fascinating in just how…labored it looks. Koontz uses the English language like a gymnasium. Every single word seems to be slotted into place with the perfection of the stones at Sacsayhuaman.

So when does it fail?

In technology it’s sometimes said that there are no bad products, only bad prices. Likewise, there might be no bad prose styles, just bad uses of them.

King’s prose often misfires, usually for the reason that he’s applying his “chatty neighbor” style to something that should not be written in the voice of a chatty neighbor.

For instance, here’s a later passage from King’s It. It’s from the POV of Pennywise the Clown (whom we now know is the mask of an incomprehensibly ancient being).

Something new had happened.

For the first time in forever, something new.

Before the universe there had been only two things. One was Itself and the other was the Turtle. The Turtle was a stupid old thing that never came out of its shell. It thought that maybe the Turtle was dead, had been dead for the last billion years or so. Even if it wasn’t, it was still a stupid old thing, and even if the Turtle had vomited the universe out whole, that didn’t change the fact of its stupidity.

It had come here long after the Turtle withdrew into its shell, here to Earth, and It had discovered a depth of imagination here that was almost new, almost of concern. This quality of imagination made the food very rich. Its teeth rent flesh gone stiff with exotic terrors and voluptuous fears: they dreamed of nightbeasts and moving muds; against their will they contemplated endless gulphs.

Upon this rich food It existed in a simple cycle of waking to eat and sleeping to dream. It had created a place in Its own image, and It looked upon this place with favor from the deadlights which were Its eyes. Derry was Its killing-pen, the people of Derry Its sheep. Things had gone on.

Then… these children.

Something new.

For the first time in forever.

Most of it is okay. Even the technical issues (like the dangling participle in the fourth ‘graf) don’t detract from its fun, jagged energy. Gulph is a good word (an antiquated and obscure spelling of gulf), emphasising Its age.

But King keeps slipping into his homespun jus’ folks style, with comical results. “stupid old thing…dead for the last billion years or so.” King makes this unholy nightmare sound like a grumpy old man with a transmission that won’t start.

And remember, Pennywise existed before the universe did. Would it really think of people as “sheep” in a “killing pen”? That’s pure anthropomorphization. That’s like writing “Derry was Its Pallet Town, the people of Derry Its Pokemon.”

Think of how King’s inspirations – HP Lovecraft, Arthur Machen, Richard Matheson – would have handled a passage like this. Better. Perhaps far better. Whenever their weaknesses in other areas, they understood that when the sidewalk ends and the bug parade begins (to paraphrase White Zombie) the writing has to change to match.

What about Koontz?

His shortcomings become obvious when you read more than five or six of his books. He keeps coming back to the same images. Birds fluttering. Rain falling. Sun striking fire against waves. This ends up deadening instead of vivifying his prose, because you can see the merry-go-round of his mind turning around and around, cycling through the same few stock images.

Remember the opening scene of The Taking?

A few minutes past one o’clock in the morning, a hard rain fell without warning. No thunder preceded the deluge, no wind.

Here’s the first chapter of Dark Rivers of the Heart.

Without thunder or lightning, without wind, the storm had come in from the Pacific at the end of a somber February twilight.

…and the first chapter of False Memory:

[…] rotten weather in southern California was seldom accompanied by thunder. Usually, rain fell unannounced, hissing on the streets, whispering through the foliage […]

…and a middle chapter of Twilight Eyes:

Tuesday morning, the sky was without sun, and the storm was without lightning, and the rain was without wind.

Etc.

Koontz is a magician with a small bag of tricks, and the more you read him, the more (over)familiar his writing becomes.

And it’s often too heavy handed, too forced, too obviously written. Sometimes it works, other times it just gets in the way of the story. Koontz can have a show-offy quality: he wants you to know he’s rewritten every sentence fifty times. Here is a particularly annoying moment from Odd Hours. (The hero has just knocked a man unconscious with a flashlight.)

The cracked lens cast a thin jagged shadow on his face. But as I peeled back one of his eyelids to be sure that I had not given him a concussion, I could see him well enough to know that I had never seen him before and that I preferred never to see him again.

Eye of newt. Wool-of-bat hair. Nose of Turk and Tartar’s lips. A lolling tongue like a fillet of fenny snake. He was not exactly ugly, but he looked peculiar, as if he’d been conjured in a cauldron by Macbeth’s coven of witches.

The “eye of newt” part was kind of cute. But Koontz can’t resist explaining the joke. “Look, everyone! I’m quoting Macbeth!”

While we’re dropping quotes, here’s another one: “Good prose should be transparent, like a window pane”. George Orwell said that. At its worst, Koontz’s writing is like a stained glass window. Impressive and admirable, but it poisons your view of what’s on the other side.

Koontz and King could both be considered masters. Study their books: you’ll learn a lot. But the final lesson any master can teach is that there are no masters, that by copying another author we copy their limitations, and that the student must someday leave the sensei’s path behind and walk their own.

1 Comment »

I enjoy reading Paul “the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine” Krugman’s opinions on things. I learn so much from his large and abundantly folded brain. For example, here he argues that conservatives are mostly incapable of modeling the thought processes of liberals.

[…] if you ask a liberal or a saltwater economist, “What would somebody on the other side of this divide say here? What would their version of it be?” A liberal can do that. A liberal can talk coherently about what the conservative view is because people like me actually do listen. We don’t think it’s right, but we pay enough attention to see what the other person is trying to get at. The reverse is not true.

You try to get someone who is fiercely anti-Keynesian to even explain what a Keynesian economic argument is, they can’t do it. They can’t get it remotely right. Or if you ask a conservative, “What do liberals want?” You get this bizarre stuff – for example, that liberals want everybody to ride trains, because it makes people more susceptible to collectivism. You just have to look at the realities of the way each side talks and what they know. One side of the picture is open-minded and sceptical. We have views that are different, but we arrive at them through paying attention. The other side has dogmatic views.

What do you think? Yes, it’s smug and a bit self-congratulatory. Paul Krugman has identified as one side of the political divide as wise and open-minded, and by complete coincidence it’s the side he belongs to.

But maybe there’s something to what he says. I’ve long felt that conservatives often do a poor job of understanding the liberal view of things, and that liberals typically do a better job of understanding their opposition.

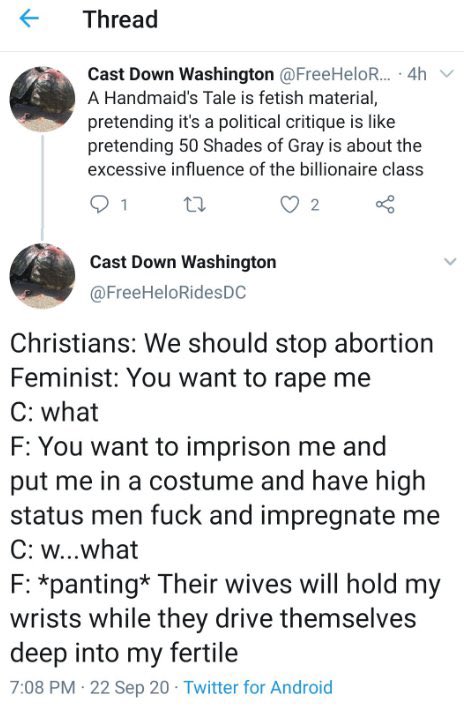

The repeal of Roe v. Wade in the United States has proven that I was wrong. American liberals, on this issue, have no idea why conservatives believe the things they do, attributing to them instead cartoon villain motives and implausible conspiracy theories that make George F Will’s “trains = collectivism” theory seem the rarified heights of sanity.

On the day the news was announced, perhaps 10-20% of Twitter changed their avatar to either a coathanger or a Handmaiden outfit. This was the start of an attack on civil rights that is solely motivated by oppressing women. Reddit had some kind of psychotic break. Many of the posts below had hundreds or thousands of upvotes.

How to turn women into “breeding cows”?

-

Overturn Roe v. Wade

-

Forbid contraception

-

Criminalize any attempt to get an abortion out of State

-

Try making it these applied all over the country

These religious crazies are spiraling down and trying to create an american white christian Theocracy!

And

The white supremacists are trying to force breed more white supremacists…and yes, I said it!!!

And

It’s a forced-breeding program. Women are chattel to these people.

And

In a 6-3 decision, women are now brood mares for the state.

And

I wonder if there’s any correlation between RvW being overturned and the U.S have consistently declining birth rates for years. If people stop having children, there’s no more generations of workers to exploit and propagandize through the school system.

And

No. Call it what it ultimately is.

In general pumping the birthrate will be good for the economy in the long run, if traditional economics stays true, but it’s hard to imagine that the GOP is thinking more than 2 elections ahead.

And

That’s what this discussion has always been about. Are women people or are they incubators?

But the pro forced birthers are unwilling go actually come out and say that because then their obvious misogyny will become apparent.

And

Gotta keep the poors churning out more exploitable youths to feed the military, prison and labor industrial complexes.

And

What they’re hoping for is more republican voters. They know they’re becoming the minority and they need more kids born in the US to attempt it.

And

No one would ever willingly fuck a republican and carry it’s gross little fucking monster seed to term, so they gotta boost those rape baby numbers.

Republikkklans envision a world where they can rape a woman and force her child into slavery, meanwhile everyone else is too distracted all the goddamned bullets to focus on their legion of evil.

And

It’s slavery with extra steps. Lots of these kids will eventually end up in jail and using Prisoners as free slaves has been a thing for a long time in the US.

Basically, how do you know what’s on a person’s mind? You really can’t. The fastest way to get an idea is to ask them why they believe what they believe: sometimes they lie, but you can’t assume that as a default explanation. Anti-abortion activists claim to be motivated by the idea that a fetus’s life has some kind of moral value. Absent other evidence, they should be believed.

George Carlin may have been patient zero for this kind of “Christians oppose abortion because they want more soldiers” stuff (though here’s an earlier version by Marge Piercey). He was a cynic. A small amount of cynicism can be healthy, just like a small amount of wine can be healthy. George Carlin was a falling-down drunk on the verge of liver failure.

Conservatives want live babies so they can raise them to be dead soldiers. Pro-life… pro-life… These people aren’t pro-life, they’re killing doctors! What kind of pro-life is that? What, they’ll do anything they can to save a fetus but if it grows up to be a doctor they just might have to kill it? They’re not pro-life. You know what they are? They’re anti-woman. Simple as it gets, anti-woman. They don’t like them. They don’t like women. They believe a woman’s primary role is to function as a brood mare for the state.

How does he know that this is what they believe? He doesn’t, and also probably doesn’t care. There might be seven words you can’t say on TV, but the market for lazy caricatures of one’s political opponents is as wide and as deep as the ocean.

Speaking of lazy caricatures, this is another one. But at least it’s funny.

No Comments »