David Bowie’s career resembled a story, and in 1983 the story became an outright cliche: he hit triple cherries with Let’s Dance, his career ascended to never-before-seen heights, he flew too close to the sun, his albums became confused and over-calculated parodies of themselves, his old fans rejected him, his new ones moved on past him, everything was falling down around him, he starred in a big budget Fraggle Rock adaptation or something, etc, etc.

Tin Machine was supposed to fulfill the “triumphant comeback” part of the story. Back to the basics! No more synths, and no more selling out! Here comes Bowie, fronting a rock band! If that sounds wonderful, here comes the pain: Tin Machine’s 1989 debut is absolutely awful. It isn’t a reinvention, it isn’t a return to form, and compared to his derided mid 80s work, it’s actually worse in many respects.

The album is smug. This is hip, happening music for hip, happening people, and you can imagine it sneering at the records you’re shelving it with. Twenty years earlier, Bowie wrote “Join the Gang”, a song inspired (in part) by his exclusion from London’s counter-cultural artistic cliques. If they’d known he had this record in him, they’d have ushered him in through the VIP entrance. Tin Machine I is straight outta Gangland.

As mention, Tin Machine’s “hook” is that it’s a band. As with Eminem’s D12, you’re not supposed to notice that it contains one of the biggest stars in music (the cover underscores the point, with Bowie occupying the least amount of space out of the four). His bandmates are Tony and Hunt Sales (of Iggy Pop fame) on bass and drums, and Reeves Gabrels on guitar. Gabrels would eventually become the Ronson and Alomar of the 90s: Bowie’s trusty hired gun, and collaborator on many great songs. Here? SKREEK SKRAWK REE WEEDLE WEEDLE KERRRAAAANGG. There – you’ve heard his entire performance.

Hunt Sales is just irritating, pounding songs into the ground with flurries of 16th note snare fills. On some tracks (particularly the coda of the first one) his drumming approaches outright aural sabotage. TMI‘s music was written in a spontaneous, quasi-improvised fashion: for this to work, the four members need chemistry, and the low-grade telepathy of sidemen who have worked together for a long time. None of that intuition is on evidence here. It’s a three legged race, everyone tripping each other up.

The album’s problems become manifest as soon as “Heaven’s in Here” starts choogling away. Loud, noisy, and boring, it’s one of the worst songs on the record. “Tin Machine” sees Reeves yanking an interesting melodic idea from the upper frets, and Bowie follows it up with…nothing. “Take me anywhere!” How does the cut-out bin sound? “Prisoner of Love” is Dire Straits made dull and nondescript: it’s the musical version of a paving slab. “Crack City” is dumb (in an ironic nod-and-wink way), rocking out with a hard-edged riff and a pretty powerful chorus. Apparently the lyric is based off Nassau, where part of the album was recorded.

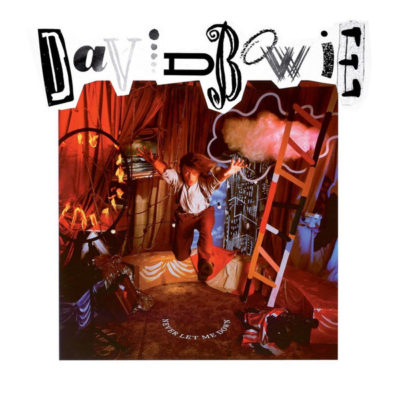

Health check: we are now nineteen minutes in, and have heard two good riffs and one good chorus. You call that a comeback? This is pathetic. Those junk Bowie bonds had a better rate of return. Scary Monsters gives you twice as many inspired ideas five minutes after you drop the needle, and at least Never Let Me Down offered up “Time Will Crawl” by now!

“I Can’t Read” is interesting, because it contains all the things that make Tin Machine insufferable (Reeves overplaying, Sales overdrumming, noise instead of coherency)…but it ends up being captivating. Bowie’s vocal is as raw and ugly as a half-bandaged wound as he ponders writer’s block (a topic addressed in “Sound and Vision”, although the two songs have no other similarities). At the end, he comes apart entirely. I don’t know how much of it as an act, but it’s a powerful moment.

The rest of the album blunders and crashes to its conclusion, offering up the occasionally highlight. “Bus Stop” is energetic and fun as hell – an uncharacteristic brush with hardcore punk. “Working Class Hero” can fuck right off. It joins the rare class of songs I literally cannot listen to because they make me angry (the class valedictorian is “Yassassin”, with “God Knows I’m Good” as salutorian and “The Buddha of Suburbia” third in class).

The reason I dislike alt-rock (a style that TMI is heavily inspired by), is that it holds the listener in contempt. You don’t play Nirvana’s In Utero, you’re condescended to by it. It’s smart, you’re dumb, now here’s ten more tracks of underproduced fuzz so you get the point. Bowie’s music was always clever, but it never tried to be better than the listener. “Sweet Thing” and “Warszawa” invited you to understand then. TMI is fifty-six minutes of Bowie and company gurning and giving you the finger.

All the excesses of the grunge era are here, several years too early. Bowie didn’t even fully succeed in escaping his pop persona, after EMI sulkingly released the album with stickers advising buyers that it was made by the guy who did Let’s Dance.

No Comments »

David Bowie (it is known) often used characters, such as Ziggy Stardust, The Thin White Duke, and The Other One.

Here, in 1987, we see the debut of his shortest lived and most controversial character: Suck Man.

Suck Man’s origins are shrouded in mystery. He appeared once on this album, and then never again. David himself never spoke about him, and some Bowie historians claim he never existed at all. But by carefully listening to this album (from another room, wearing a HAZMAT suit) I can now reveal his full, tragic story.

Who is Suck Man? Essentially, he is the sad remains of a once successful rockstar, haunted by his glory days. He has no grasp at all on what his fans want or what might sell, so he’s trying to do everything at once. French horns? Here you go! Rapping? Yeah, he can do that too! Guitar solos? You bet! How about french horns, rapping, and guitar solos all at once, thrown together in a way that doesn’t make sense?! Imagine a whole album like that?! W…Wouldn’t that be wonderful?

Suck Man is not a malicious figure. He’s sad, and pitiable. He clings to your ankles, begging for your acceptance. He’ll do anything. He just wants to be loved. If only he could be a hero again, if just for one day.

Never Let You Down is extremely bad, but at least it’s not bad in a boring way, like Tonight, or in an insufferable way, like Tin Machine I. It has entertainment value. There are songs I’ve listened to more than legit good Bowie tracks, and that’s saying something. The most obvious things wrong: the ridiculous production and arrangements. These aren’t songs, they’re crime scenes. The gated snare drum is obnoxiously loud. The backing singers are hideously overbearing. Bowie’s vocals vacillate between R&B and proto-Britpop. The album really does sound like 2 or 3 Michael Jackson tracks playing over the top of each other, all out of step.

It actually contains a little bit of good music – maybe more than Tonight did. “Time Will Crawl” has a cool, slinky saxophone line and a set of strong musical ideas. The Iggy Pop cover “Bang Bang” cooks nicely and ends the album well. Both these songs have twenty things shoved into them that don’t work and which I outright hate, but I see the skeletons of good music inside the layers of cancerous blubber.

Midway through the burnout of this musical Hindenburg, we get “Glass Spider”, which is not the worst song, but certainly the most embarrassing. Baby spiders have lost their mommy. Suck Man practically gift-wrapped this track for you. Not only is this track on the album, he actually titled the accompanying toured, and it was the second track. For God’s sake, at least Paul McCartney had the decency not to subject us to a “Wonderful Christmas Time” tour!

Suck Man also likes socially conscious lyrics. This was the era of Live Aid and Hear ‘n’ Aid, where every rockstar wanted to make a difference. Don’t ever play this to a former African child soldier. The gated snare will trigger PTSD flashbacks to AK-47s in the trenches of Sudan.

The rest of the album is ghastly. You listen in morbid fascination. Believe it or not, there’s an even worse track (“Too Dizzy”) that Bowie took off the record out of shame. Imagine being too bad for Never Let You Down – it’s like playing Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out and getting KO’d by Glass Joe.

No Comments »

“Transition…” – David Bowie, “TVC15”, Station to Station

He was right to muse on it, because transition is interesting. Not medical transition (though that must have intrigued him also), but philosophical transition. Ship of Theseus. Lumpers vs splitters. Much of philosophy is based around the question “when does a thing become something else?”

Is transition a continuum, like day becoming night? Or can it be quantified into discrete steps? Historians have spent countless hours wargaming World War II, trying to isolate the point where Hitler definitely lost. Was it 1940, when the Luftwaffe was crushed in the Battle of Britain? 1941, when the United States entered the war on the Allied side? 1942, when Stalingrad held? When was the final moment that Germany could have won World War II, and after which, they absolutely couldn’t? And how thinly can we slice the bratwurst? A month? A day? A single second?

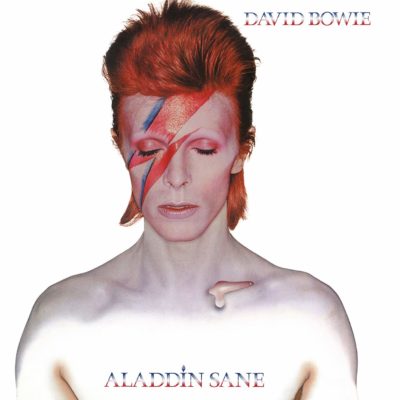

Aladdin Sane is an exposition of transition. We see Bowie at a cracking point, where fame was becoming overwhelming, a burden. He invented a new character, a guy with worms filling his brain and white-ants eating his bones, but his confusion was no fiction. Over the next year his backing band would either leave or get fired, unable to handle his egomania and drug abuse. The paranoid Berlin years have their genesis here.

Musically, it’s fierce and punishing: along with The Man Who Sold the World, this is the heaviest thing Bowie ever recorded. But it has an experimental side that, again, seems like a preview trailer for Berlin. Transitions. Beginnings and ends.

We see both sides of the album, right out of the gate. “Watch That Man” is a loud party song – Bowie (perhaps in character, probably not) is at a party, noticing scenes of glitz and glamour and pronouncing them merely “so-so”. Maybe it’s not even that. Maybe it’s about to become a nightmare.

“Aladdin Sane (1913-1938-197?)” is the end stage of that party. The song is dominated by a 45-bar avant-garde jazz solo by pianist Mike Garson. Surely Bowie’s brilliance was becoming impossible to deny by now. Damned well nobody else was doing stuff like this in 1973. What’s the meaning of the dates in the titles? 1913 was the year before World War I. 1938 was the year before World War II. Does this mean that Bowie thought that the third World War would happen in the 70s? And did it?

“Cracked Actor”, “Jean Genie,” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together” are homages to or parodies of the Rolling Stones. The guitars crush and maul, and his vocals sound both inspired and exhausted. “Time” sees a new influence popping up: Jacques Brel, who he discovered via Scott Walker. “The Prettiest Star” is a lovely song: it was originally his failed second single, here remade with Ronson’s guitars and some added backup vocals.

The album overflows with great music, but two songs overshadow the others.

The first is “Panic in Detroit”, anarchic and violent, a track which burns with the guttering energy of a trash fire. The female backing vocals pull its genre way from rock, making it sound as indeterminate as any riot. The second is “Lady Grinning Soul”, a delusive opium dream made music. I like it every bit as much as “The Bewlay Brothers”, which means Bowie scarcely ever wrote a better song.

Aladdin Sane is far tighter (and a good bit better) than Ziggy Stardust. The Mick Jagger meets Jiminy Cricket character of Ziggy Stardust evolved into Aladdin Sane, a manic guy caught between two transition points and being torn apart by fame. The trip is finishing, and the come-down has begun. This is 3am insomnia, the album: paranoid, anxious, and still unable to sleep.

No Comments »